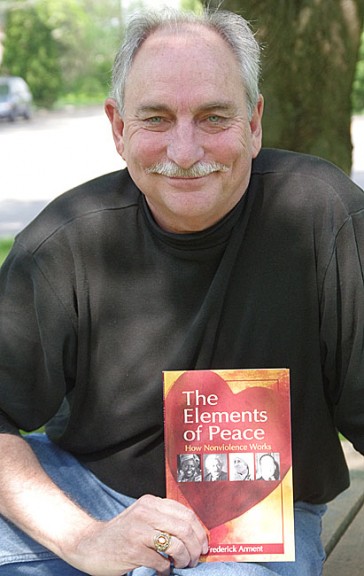

New book’s paths toward peace

- Published: May 17, 2012

Forgiveness. Attentiveness. Dissent. These might seem like disparate themes, but to Fred Arment they all have one thing in common: they are among the “virtues” that guide the work of advocates for nonviolence. Arment explores this idea in his new book The Elements of Peace, which identifies 30 virtues in all and illustrates them with a wealth of examples. From sustainability, embodied by the late Green Belt movement leader Wangari Maathai, to balance, as promoted by Doctors Without Borders, Arment celebrates the variety in people’s motivations for embracing positive nonviolent action.

Arment has been part of the peace movement since his early 20s.

“When you grew up in the ‘70s, the early ‘70s in particular, there was lots of pull on which way people should go, fight for peace or tuck into the regular world…a lot of us at that time decided to choose between violence and nonviolence,” he said in a recent interview.

Arment co-founded the Dayton International Peace Museum in 2004, nine years after the Dayton Accords ended the war in Bosnia. He’s also the director of International Cities of Peace, a group he helped create in 2009 to bring together municipalities that have a unique place in the history of peacemaking.

Cities of Peace has developed the idea that “safety, prosperity, [and] quality of life” are the “consensus values of peace.”

“People are so polarized and argumentative about everything, but that has really resonated with everyone we’ve talked to,” said Arment.

Yet, while people seem to agree on what characterizes peace, they disagree on how to bring it about.

“At the museum…everyone who walked in that door had a different take on peace and many thought their way to peace was the only way to peace,” he said.

This inspired Arment to ask, “why is the nature of peace so individual?” He concluded that “it has to do with our character traits and what we value.” In other words, it “depends on what your personality is, what way you choose to work for peace.”

This idea led to a new exhibit, “16 ways to work for peace.” The exhibit was eventually expanded several times, until the original number of “ways” had almost doubled. Indeed, “there seem to be 30 specific ways to work for peace,” said Arment.

Thus, “this book focuses on 30 methods and characteristics, 30 different individuals…each [was] able to use their time in history and their characteristics to make a difference, and each of us has that opportunity,” said Arment.

Nelson Mandela is one leader profiled in The Elements of Peace.

“He started fighting for peace, he was put in jail for armed attacks, but came to know nonviolence and that it was the way to get rid of apartheid. But he didn’t stop there. He knew that after [a] treaty, you have to prevent bloodshed. Mandela had the virtue of forgiveness, which I believe allowed him to see the path forward. He knew that his enemies needed to be freed as well as his compatriots,” said Arment.

Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who was posted to Hungary during World War II, is also profiled. “He saw Jews being shipped to concentration camps,” said Arment. “His characteristic of empathy drove him toward a heroic effort of giving thousands of passports to allow Jews to leave before they were captured.”

Advocates like Arment face certain obstacles when trying to convince people of their power to be peacemakers.

“There are lots of preconceived notions about peace,” he said. He sees his book as “brushing away the fear, [giving people] the courage to find our own course of action.”

While it might seem that violence dominates human society, Arment argues that the opposite is true. In the book he quotes Gandhi, who said, “acts of love and service are much more common in this world than conflicts and quarrels.”

“99.9 percent of our activities are peace-related, but violence has corrupted our lives,” said Arment.

This negativity is encouraged by “people that love power,” said Arment. “It’s a way of domination…[arising from] the negative side of religion, politics, wealth accumulation. All of those depend on us feeling a bit of fear and fear is really the problem.”

While problems such as the threat to the environment from the burning of fossil fuels can seem overwhelming, there is reason for hope, he maintains.

“Just in this town we have a huge environmental movement,” he said. He noted YSI’s development of technology that measures changes in climate, helping to expand our understanding of global warming.

Arment tries to steer readers clear of another potential stumbling block: perfectionism. In the book’s conclusion, he writes: “to always be good and right in every situation, every moment of our lives is neither possible nor a requirement for peacemaking. We realize there is no such thing as a perfect person, so most of us endeavor to become the best we can be. That is what we call individual human progress…our quest as peacemakers is to evolve our innate and acquired abilities to make positive changes in an imperfect world.”

Meanwhile, “you have to have a bit of peace in your life, and if you approach peace pushing through chaos you’ll create chaos.” Inner peace comes about through personal transformation, and arises from the virtue of “unity.” Neuroscanning experiments show that Buddhist monks and Catholic nuns have the same electrical brain response during meditation, said Arment. This “not only shows that we should be tolerative of other religions but that we can all find a sense of unity by personal meditation practices, whether that’s riding a bike, walking in the woods or praying in a church.”

He’s pleased with the reception of the book, which he said is enjoying “pretty good sales.” He added that a number of college conflict resolution departments have expressed interest in it. High schools, peace organizations and home schoolers are also among his intended audience.

Arment is already at work on his next book, The Economy of Peace, at the urging of his publisher. In it he plans to address the question, “What will be the character of our economy in a post-capitalist and post-socialist world?”

“Within this century,” said Arment, world economies will experience “remarkable change…and nonviolence is already a huge part of that change.”

The Elements of Peace is available from the publisher, McFarland & Company, as well as the major Internet booksellers. It can also be ordered locally from bookstores in Yellow Springs.

“It was a really interesting book to write,” he said. “It’s solved a lot of questions for me,” such as, “‘Why do people work in different ways for peace?’” and “‘What is it about my character that drives me to work for peace in my way?’”

As for his own guiding virtue, Arment said, “I think I’m an extreme optimist. I choose not to see the world as bad.”

If not everyone can muster this attitude, that still leaves 29 other virtues for potential peacemakers to discover in themselves.

No comments yet for this article.