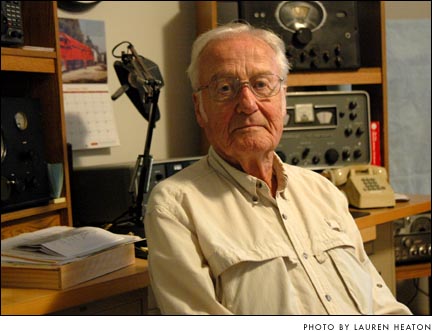

Longtime villager and YSI Incorporated founder Hardy Trolander was honored last month when he was inducted into Dayton’s Engineering and Science Hall of Fame. Trolander’s childhood love of taking radios apart, to which he has returned in his retirement, led to his lifelong interest in invention.

Trolander’s lifetime of triumphs

- Published: December 18, 2008

The early radio was one of the simplest electric circuits that existed in the 1930s, but for a monumentally curious 10-year-old Hardy Trolander, that mysterious machine was the door to a lifetime of inventing and improving the art of problem-solving.

For his contribution to biomedical sciences through YSI, Incorporated, the engineering company he co-founded 60 years ago, Trolander was recently honored by Dayton’s Engineering and Science Hall of Fame. The recognition is local, but it enshrines Trolander with the likes of world-reknowned scientists Linus Pauling, Jonas Salk, Mary Leakey, Buckminster Fuller and the Wright brothers. And though he doesn’t think of himself as personally meriting any lofty distinction, he is proud of the contribution to humanity that he and a team of dedicated colleagues were able to achieve.

Trolander had a lot of early “triumphs,” he said in a recent interview. Growing up on the outskirts of Chicago, Trolander spent a lot of time in the basement of his family home disassembling secondhand radios from the 1920s and using the parts to make new radios, which, to his astonishment, worked.

“Mother thought it was enterprising, but then I brought home so many that she thought I was too enterprising,” Trolander said, glancing sideways with a smirk.

But Trolander had stumbled onto a lifelong passion and was hooked on electronics. He started hanging around a neighborhood radio repair shop to learn a few things and eventually got hired to work there.

“I got paid $1 a day for something I wanted to do — it was terrific,” he said.

And when he found an early TV in the shop owner’s attic, he purchased that too, with the help of an employee discount, and worked with it until he could receive at least three stations at night from Purdue, the University of Iowa and Kansas State University. His next project was to broadcast a station, which he did illegally, just long enough for a co-conspirator to pick up on the radio a few houses down the street.

Slightly older but just as curious, Trolander wanted to test his theory on the mechanism that caused the railway crossing gates to descend at an intersection. He brought a friend and a thick copper wire he had scavenged to the Rock Island railroad junction and held his end against one rail while his friend held the other end against the opposite rail. Hail! The gates came down because of what he had known was a low-resistance pathway between the two rails. It was a huge triumph.

“That was one of the most productive pieces of reasoning I ever came to,” he said. “In a sense, my speculation on how the gates came down was a form of invention.”

Emboldened, and attracted by Antioch College’s co-op and liberal arts program, in 1940 Trolander headed off to Yellow Springs. Attracted to radio again, but this time as a program host, he and his roommate, David Case, broadcast classical and national folk music on WYSO. He, Case and two other friends, John Benedict and David Jones, also had a fondness for automobiles, especially sports cars… “and maybe hot rodding a few,” Trolander said. At Antioch Trolander also met and married his fellow classmate, Gene.

The four engineers shared enthusiasm for the enterprise that Arthur Morgan had encouraged in building a self-sustaining community. That entrepreneurial community was already flourishing on and around the campus with Vernays and Morris Bean starting up, as well as the hybrid corn and the Antioch shoe projects in Portsmouth, Ohio, and the Fels and Kettering Labs research. And Trolander was getting an inkling that, with the help of his friends, they too could start something innovative.

But first, called by a sense of adventure and patriotism, they got waylaid by a stint in the service. And when they returned to campus, more mature and hungry for camaraderie, they found a renewed sense of their own ability to help change the world. Trolander and Case were trained as electrical engineers, Benedict as a mechanical engineer and Jones as a chemical engineer, and all four were out teaching, researching or doing graduate work. So when Trolander pitched his idea in the summer of 1948 for his new business, they all came back to Antioch to try and make a go of it from the basement of the college science building.

Problem solvers all, the team started a company not to fill a particular commercial need, but to solve technical problems.

“We wanted to use the business as a vehicle rather than the business as a primary aim,” he said. “I’m not a believer in long-term planning. We wanted to make more and better instruments. Period. End of business plan.”

Their initial work came from Fels, Kettering and Wright Patterson Field, which brought measuring and testing equipment for either repair or redesign. One of the most complicated early projects was the flash timer on a tachistoscope, a device used to measure the persistence of vision, such as with target recognition for pilots and bombardiers. The company’s first commercial instrument was the dielectric constant meter, which measured the stability of a liquid suspension. And YSI also worked with Fels researcher Leland Clark on developments for the heart-lung machine.

Trolander and his small team didn’t want to have too much success with any one product because they didn’t want to be cornered into manufacturing, he said. They aimed to stay in the small market of state-of-the-art instrumentation, which would allow them to be creative.

“There are always technological challenges, and some we solved and some we didn’t…but we solved enough to eat. It was an engineering approach to business,” he said. “And we had a hell of a lot of fun.”

And that was how they liked it. For a while.

Then YSI began presenting technological papers more widely, establishing connections abroad and entered into a joint venture with a group of Japanese scientists to build a plant in New Mexico and focus on temperature, oxygen and conductivity measurement tools. And, intentional or not, things began to grow. The company built its facility on Brannum Lane and hired a number of new technology specialists, including Ray Schiff, Tom LaMers, David Newman, Jeff Huntington, Alan Brunsman, Jay Johnson, John Zurbuchen, and the list goes on.

“While you can’t budget for invention, if you put enough technical people together and give them enough freedom, an invention will occur,” Trolander said.

Trolander retired as CEO of YSI in 1986. One of the things he is most proud of from that time is the company’s personnel policies, which were based on trust and an early notion of corporate social responsibility. In Arthur Morgan’s model, YSI would be a company that respected and had the respect of its employees and the community in which it operated.

And the work he is most proud of is the discovery of the official melting point of gallium as an international standard. YSI had an interest in pursuing the sciences as an art, and for Trolander, that was experimenting to establish a standard that would be a worldwide reference point.

“Different states of matter are determined by constants of nature, such as the triple point of water where the cell is a vapor, a liquid and a solid at once,” he said. “It’s beautiful, that phenomenon, it defines that temperature. And it takes a lot of skill to get a cell to maintain that temperature.”

With Phil Metz in the standards lab, YSI found 5 nines pure gallium from Switzerland and established the melting point of that element at 30 degrees Celsius. In 1974 it was on the market, and in 1990, it was adopted as a practical point on the International Temperature Scale.

“A thousand years from now, in the footnotes of the scale, you’ll see ‘YSI,’” Trolander said with a smile. “It held a lot of prestige and gave us credibility in the market place. It was a merit badge more than the thing itself that YSI had established itself.”

Trolander was personally recognized in 1992 when he was elected as a member of the National Academy of Engineering, where he served on the selection committee for the Fritz J. and Delores H. Russ prize from 2001 to 2007.

Though Trolander can look back on a lot of years of success, he maintains his characteristic interest in doing exactly what he started with, fixing old radios. In the bedroom of his Friends Care Community independent living apartment on Aspen Court, he keeps five 1930s short wave radios, all of which work. One is tuned to a Xenia AM weather station, another brings in a news station from Australia every morning, and the one placed by itself in the very center of the desk is tuned in to the Denver clock’s local standard time.

No comments yet for this article.