|

Film brings a WWII secret to life

|

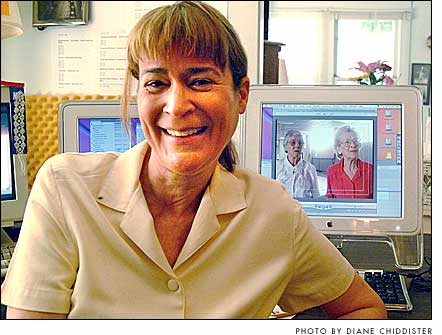

Aileen LeBlanc in her home office,

where she produced a documentary, "Dayton Codebreakers,"

about a top-secret program at NCR during World War II. On her

computer screen are two former Navy WAVES who worked on the codebreaking

project.

|

By Diane Chiddister

Since she left her job as news director at WYSO

Public Radio two years ago, Aileen LeBlanc has not been sitting still.

Rather, she has been doing what she loves best — learning new skills,

finding good stories and digging into local history.

The result of her work over the last two years is a

new documentary, “Dayton Codebreakers,” which premiered last

Friday at the University of Dayton. It will also be shown on ThinkTV channel

16 on Saturday, April 23, at 8 p.m., and on ThinkTV channel 14 on Sunday,

April 24, at 9 p.m.

The film tells the story of a previously little-known

nugget of Miami Valley history. In the early 1940s the United States government

called upon Joe Desch, a Dayton engineer who worked at NCR, to run a top-secret

program aimed at developing the technology to break the codes of the Germans

and Japanese. With the help of a small group of engineers and a large

group of Navy WAVES, Desch developed a high-speed codebreaking machine

called the NCR bombe that contributed to ending World War II.

LeBlanc, who produced the film, first covered the story

of the NCR bombe when she interviewed Desch’s daughter, Debbie Desch

Anderson, for a short segment on the WYSO program “Sounds Local,”

which LeBlanc produced and hosted.

The story continued to haunt her, LeBlanc said.

“I felt the story had to be told,”

LeBlanc said in an interview this week. “I felt inspired to do it.”

While the codebreaker story had been written in an

eight-part series in the Dayton Daily News by reporter Jim Debrosse, who

went on to write a book on it, both LeBlanc and Anderson wanted to present

the material in a film. They hoped a film would attract young people to

the story, said LeBlanc, who believes that film captures human emotions

that the written word may miss.

“I’m a broadcaster,” she said.

“I want to tell stories through sounds and images, to allow people

to express themselves.”

LeBlanc and Anderson became friends and began working

together on the project. They researched archival materials, hunted through

old photos and interviewed surviving project veterans who, told to keep

silent about their work 60 years ago, had never told their stories. The

two also discovered treasures in the boxes of material that were stored

in Anderson’s basement since her father’s death in 1987.

LeBlanc soon discovered that she and Anderson had uncovered

a wealth of information about a powerful story. There was only one problem

left — while LeBlanc had spent her adult life working in television

and radio, she had never before made a film.

“I thought that editing video wouldn’t

be much different than editing audio. I was so wrong,” she said.

“I didn’t know the technology and it almost sunk me.”

But not knowing how to make a film didn’t daunt

LeBlanc — she just decided to learn. She tackled film editing software

and received help from local filmmakers Jim Klein, Julia Reichert and

Steve Bognar. She made a lot of mistakes and learned how to fix them,

she said.

If she hadn’t learned how to make the film herself,

LeBlanc knew, it wouldn’t be made. She had no funding initially

and couldn’t afford to hire many professionals. LeBlanc and Anderson

raised $98,000 in donations for expenses, a remarkably low amount for

a film, and did most of the work themselves.

They began work on the film before they secured funding

because NCR, which owned Building 26, where the codebreaker project took

place, had decided to sell it. The two women also felt time pressure because

those involved in the codebreaker project had either died or were elderly,

and the filmmakers wanted to get their stories before it was too late.

Making the film has been a full-time job for the past

several years, LeBlanc said, and now her efforts have paid off. At last

Friday’s showing at the University of Dayton, the film received

a standing ovation from the full-house audience.

Finishing the film has been good news, but the bad

news is that now LeBlanc may need to leave the area. She needs a job,

she said, and has applied to radio and television stations in Columbus,

Cincinnati and Virginia. LeBlanc also applied for the job as general manager

at WYSO, where she worked more than three years before leaving her job

due to difficulties with Steve Spencer, who was the manager at the time.

However, LeBlanc was not one of the finalists for the general manager

position.

LeBlanc said she doesn’t look forward to leaving

Yellow Springs.

“There’s something in the air here

that suits me,” she said. “The best friends in my life are

in Yellow Springs, Ohio.”

|