|

|

Installment

3: 1868 to 1883

Period

of growth and easy living

|

|

PHOTO COURTESY OF ANTIOCHIANA

The Livery Stable on Dayton Street was a popular gathering place

for local residents in the late 1880s. This picture shows downtown

Dayton Street, near the location of the modern bikepath.

|

Two decades or so

after Yellow Springs was incorporated, the village was apparently working

through the fits and starts of a growing community.

During the period of 1868 to 1883, businesses sprouted up in the central

business district, the school district consolidated white students into

one large building, Union School, and many civic organizations met regularly.

In a 1956 three-section special commemorating the centennial of the incorporation

of Yellow Springs, the News described the period between the Civil War

and the end of the 19th century as a “rather quiet” one. “The

village grew quietly, lost some of its frontierish atmosphere and settled

into an easy pattern of living,” the News reported in an article

on the town’s early years.

“The many societies and social organizations, at the college and

in the village, played an active role in the social life of the period,”

the article said. In addition, many of the businesses in town, including

the general stores, the post office, railroad station, drug stores and

the livery stable, near Corry and Dayton Streets, were popular gathering

places.

In 1870, according to a paper on businesses during this period at Antiochiana,

the Antioch archives, the village was home to six churches, three hotels,

six dry goods stores, three grocery stores, a bank and two drug stores.

By this time businesses were located on Xenia Avenue to Glen Street in

what today is downtown. Frank Hafner ran a bakery where Ye Olde Trail

Tavern stands today. He also sold coal. W.G. Whitehurst was a telegraph

operator on Xenia Avenue.

Carr’s Nursery opened in 1870. Its nurseries were located on South

High Street and on both the east and west sides Herman Street. The business

also had an office on Dayton Street, near the Union School House. It sold

fruit, trees, vines and flowering shrubs, evergreens and roses.

Like the rest of the nation, Yellow Springs was affected by the “Panic

of 1873,” a depression. For instance, in a letter from James G. Adams

to William C. Russel, a former Antioch professor and prominent landowner

in town, Adams writes that rental rates have fallen.

On Oct. 9, 1880, the Yellow Springs Review published its first issue.

The paper would eventually become the Yellow Springs News. Its first office

was located at or near today’s A-C Service building.

A few years after the “Panic of ’73,” things appear to

have changed. In its Nov. 13, 1880, issue, the Review said that Yellow

Springs businesses offered everything anyone would ever need, “but

at cheaper rates than most places, especially larger cities.” The

paper’s editor, Warren Anderson, attributed this to the fact that

living in the village is cheaper, “rents are lower and most business

is done on a cash basis.” At the time there were more than 35 different

places of business in town, the Review reported.

One of those businesses was Chas. Shaw, which, the Review said, was run

by “the oldest and most successful commercial men at the Springs.”

The dry goods store had three clerks who are “always busy.”

As the Review noted, in the early 1880s, most businesses preferred to

work on a cash basis than on credit. “When cash wasn’t available

even in that day of the railroad and the telegraph, farm products would

serve as payment,” the News reported in 1956.

In 1870, a new railroad station was built on Corry Street near Xenia Avenue,

and two to four different rail lines offered passenger services here.

Passenger trains traveled to as far away as St. Louis, Chicago and New

York. The railroads were also an important part of the economic life of

the village. Horse and buggies were a primary means of transportation

around town.

The first sidewalks were built in town in 1870 when two businesses, J.D.

Hawkins and the Hirst Brothers, laid down birch walks in front of their

shops. But apparently muddy streets and sidewalks remained a problem,

and a complaint, throughout this period.

|

|

PHOTO COURTESY OF ANTIOCHIANA

Tea parties were fashionable in the 1880s. This photo includes the

McClure twins as well as the stepdaughter of William Mills, second

from left.

|

Of course, Yellow

Springs featured several resorts, including the Neff House Park Summer

Resort and the Yellow Springs House.

The Yellow Springs House was located where the Bryan Community Center

is today and was run by E.P. Johnston in 1870. But apparently, the Yellow

Springs House went through many changes and a number of proprietors.

The Neff House was the second resort of the same name and was owned by

the sons of William Neff, who opened the first Neff resort.

But even from its first days, the new house struggled. Scott Sanders,

the Antioch University archivist, said that the Neff House organized a

grand opening celebration that no one attended. It apparently was put

up for auction six times between 1872 and 1874. The grand resort eventually

closed just 12 years after it opened, in 1882.

Tea parties were a

fashionable way to entertain in the 1880s, and literary societies were

popular at Antioch. The atmosphere of the societies, the News reported

in a special section commemorating the college’s centennial in 1953,

was believed to be formal and the agenda highly intellectual.

The Review reported that in 1879, “a small number of books were purchased

last spring and a literary association was formed.” Several civic

organizations met regularly, including the Freemasons and the Odd Fellows.

The Women’s Christian Temperance Union was also active in town during

this period. The union believed that the “greatest weapons against

rum are the prayers of the righteous and — the ballot box,”

the Review reported.

During this period, William Mills returned to the village he helped found.

After serving in the Union Army in the Civil War, Mills went to Kansas

where he set up a real estate business. He was financially crushed in

the “Panic of 1873,” the News reported in an article on Mills

in 1956. He then dabbled in real estate in Chicago and returned to Yellow

Springs in 1876. He peddled books for three years and died a poor man

in 1879.

The village government appears to have slowly made progress during this

period. The first jail was built in 1870 on Winter Street near Dayton

Street. In 1873 the village government purchased four fire extinguishers,

then five years later, it bought its first fire engine, a hand-drawn water

pump.

Around 1881, 68 street lamps — probably kerosene lamps — were

erected in town. The Review reported on Aug. 12, 1881, that the village

council ordered lamps to be placed in various locations on Dayton Street

and down Xenia Avenue.

In 1871, the public school district built the Union School, which at first

housed white high school and elementary school students. The building

would later become the offices of the Village government.

Black children attended school on High and West South College Streets

until 1887 when the local school district desegregated. In 1871, J.M.

Logan was selected as the first principal of the black school, according

to a paper at Antiochiana on the early history of local black schools.

At least three student-run newspapers were being published in 1873, one

of the papers, “The Public School Mirror” reported in its first

printed issue on June 12. The other papers included the “Bombshell,”

whose “professed objection” was war, the “Mirror”

said, and the “Hornpipe,” which the “Mirror” called

a “musical paper” published by the school’s Grammar Room.

Edited by four female high school students, the “Mirror” reported

on school and town news and was “devoted to the interests of the

Yellow Springs public schools.”

Sanders, the Antioch archivist, called this 15-year period “the most

boring period in Antioch’s history.”

“It’s a testament to the college’s stability” during

the period, he added. That stability, he said, was due to the fact that

Antioch had an endowment, “capable administrators and a fair number

of students.”

In fact, a baseball game the Antioch Nine played against the Cincinnati

Red Stockings, a professional team, “may be the most exciting thing

that happened on campus” during this period, Sanders said.

—Robert

Mihalek

Village’s

‘home-printed’ newspaper launched

|

| |

Troubles with moving

vehicles and dogs-at-large — in some ways, what villagers read in

the local newspaper 120 years ago wasn’t all that different from

today’s stories.

“Last Saturday night as William Dickey was returning home from Yellow

Springs accompanied by Charles and J.E. Shoemaker, the horse became frightened,

upset the buggy and tore up the ground with the boys. The Shoemakers escaped

injury, but Mr. Dickey’s left lung was mangled in a frightful manner.

Later Sunday morning a dog was seen with something hanging in his mouth,

supposed to be William’s left lung . . . but on closer examination

it was found to be a ham of mutton.”

That news item, from the April 11, 1884, issue of the Yellow Springs Review,

the predecessor of the Yellow Springs News, might have been written by

the paper’s editor, Warren Anderson, who founded the Review in 1880.

The Review published its first issue on Oct. 9, 1880.

The Review was the first successful newspaper in the village after several

failed attempts, according to an article by former News editor Kieth Howard

in the Yellow Springs News “Centennial Edition” of October 8,

1980. Previously, Oliver Farnsworth had published several issues of the

Farnsworth News in 1830, followed by at least 40 issues of The Free Presbyterian

in 1856 and ’57.

And in 1858 E.Z. Wickes and Mrs. S.J. Wickes published four issues of

Compass of Life, which proposed to “report the best speeches at Antioch

College and the racy contributions of students and faculty.” In 1874,

a paper called the Yellow Springs Ledger published a number of issues.

When Anderson founded the Review, its office was located at “the

Hamilton building, on Dayton Avenue, near J.H. Little’s Grain Elevator

and Railroad,” which places it in or near the current A-C Service

building, 116 Dayton Street.

A former Antioch College student, Anderson wrote that without a local

paper Yellow Springs business owners “have been deprived of a convenient

medium through which to herald their business abroad . . . This want is

now supplied by the Review.”

Those business people, the Review reported in November 1880, included

“T.B. Jobe, who at his Dayton Street business has carriages, buggies,

phaetons and springwagons, new and second hand, and in all styles. E.

Thornton makes harness and L. Green offers livery service (horse and vehicle

rental). There are two blacksmiths, Albert Thompson and John Pennel, to

keep the horses shod.”

As well as traveling via horse and buggy, villagers apparently rode a

lot of trains, since the Review ran ads for up to four different rail

passenger services, including trains to both Springfield and Xenia, with

stops in Beatty, Hustead, Goes Station and Oldtown, as well as trains

to Cincinnati, Indianapolis, St. Louis, Chicago or New York.

In 1880 the Review also featured ads for “Chas. Ridgeway, dealer

in drugs, medicines, chemicals, fine toilet soaps, brushes, combs, etc.,”

and Chas. Adams’s Cash Store, which sold groceries, dry goods, notions,

shirts, overalls, hardware and a “good stock of men’s underwear.”

The S.K. Mitchell & Son lumber store and S.W. Daken, attorney at law,

also advertised in the paper.

Anderson didn’t shy away from boosterism, and his first issue said

that “it is generally conceded (and it is true) that Yellow Springs

has more good-looking young ladies in proportion to the population than

any town in this vicinity, and no disparagement to other places.”

In the Dec. 8, 1882, issue, the Review printed a story carrying the headline,

“There are Many People In Our Town Who Would Like To See”:

Brick placed on our sidewalks.

Mud carted off our streets.

A new city building erected on Xenia Avenue.

The college open next term with 400 new students.

Some system to the lighting of the street lamps.

Overall, the Review said in a “house ad,” the paper was “the

Best, the Freshest, and the Only all home-printed newspaper in the county.”

—Diane

Chiddister

Rise

and quick fall of second Neff House

|

|

PHOTO COURTESY OF ANTIOCHIANA

The second Neff House, built in 1870, featured a three-story veranda;

it closed in 1882 after financial woes

|

Tourists. They never

could stay away.

From 1870 to 1888 well-to-do people from Cincinnati, Columbus and Indianapolis

flocked to Yellow Springs to visit the most extravagant hotel in village

history, the Neff House Park Summer Resort.

At the resort’s zenith, 18 trainloads of visitors a day arrived in

Yellow Springs on summer Sundays to stay in the Neff House, according

to “Yellow Springs as a Resort Town,” by Harriet Plumley, and

about 5,000 tourists at a time roamed what today is called Glen Helen,

where the resort stood near the large boulder close to the Yellow Spring.

Tourists descended on the village to visit one of the most magnificent

hotels in the region. Advertised in newspapers as “A Southern House

in the Northwest for Southerners,” the Neff House stood four and

a half stories high, with a three-story porch that hugged two sides of

the building. It housed 246 rooms, including many suites, plus 11 private

parlors, a main parlor that measured 75 feet by 45 feet and a 156-foot

long dining room. Self-sufficient, the resort included its own dairy,

orchard, garden and fire department.

And that wasn’t all. The resort included six bowling alleys and a

stable with 125 stalls, housing “many Kentucky horses” for guests’

pleasure, according to William Galloway’s The History of Glen Helen.

The dammed-up Yellow Springs Creek offered both swimming and boating,

and on a bandstand built on the Indian Mound, musicians blew their horns

into the summer nights.

The Neff House Resort was the latest in a series of successful hotels

that sprang up almost as soon as Yellow Springs’ first settlers appeared.

Initially, out-of-towners were drawn by the water of the Yellow Spring.

“The iron, or chalybeate, present in the water was believed to have

unlimited healing and restorative powers,” according to “Yellow

Springs as a Resort Area 1800-1870” by Hank Roller, a former Antioch

student. “The temperature of the water never varied more than a few

degrees from 65 and therefore was a welcome sight on an extra warm day,

sick or not. Also, the spring was believed to be the highest point in

Ohio.”

In 1827, Elisha Mills bought the Yellow Spring and set about revamping

a modest hotel operation that had been opened by the town’s first

settler, Lewis Davis. Two years later, he opened his remodeled hotel.

The hotel was later sold, but brought back into the family by Elisha’s

son, William Mills, who purchased it in 1835. Mills added on, so that

the structure grew to include 100 rooms, and made other improvements.

“Vast gardens were laid out on the south side of the place with many

intertwining walks,” according to Roller. “Several groves of

cedar and pine trees were planted between the house and the spring. The

Indian Mound, or as Mills referred to it, the Mound of the Aborigines,

was a favorite curiosity of the locality and a bandstand was later built

on it.”

When William Neff bought the resort in 1842, “he purchased a thriving,

luxuriant hotel,” according to Peggy Thompson’s “Neff House

History.” The resort included “a Mansion House, a piazza, six

cottages, a billiard house, two bowling alleys and a stable.”

Well-known for miles around, the resort, as well as the college, drew

the famous as well as the wealthy. Henry Clay and Daniel Webster were

said to have given speeches from the Mound Builders Mound, and prominent

Unitarian minister Edward Everett Hale once described Yellow Springs as

“this lovely spot, where everything seems combined that can delight

the eye, afford recreation and promote health.”

Helping to promote health was the Water-Cure Institution, a local organization

begun in 1850 “with several physicians in attendance at all times,”

drawing the infirm to Yellow Springs in hopes of being healed, according

to Galloway. However, the business burned down in 1859.

Another local hotel, the Yellow Springs House, was located at the site

of the Bryan Community Center.

In the early 1860s, several factors combined that led to the Neff House’s

downfall. William Neff died, and the Civil War further diminished business.

The hotel may have gone out of business around 1865.

Several years later, five sons of William Neff tried again. On a long

weekend in 1869, they invited several wealthy friends from Cincinnati,

Dayton and Columbus to propose building a new hotel even bigger and better

than the last. To raise funds, the Neffs attempted to sell 100 bonds for

$1,000 each, with the understanding that bondowners could, if they desired,

build a cottage on the Neff House property and live rent-free.

The idea caught fire, and $75,000 was quickly raised. The Village of Yellow

Springs chipped in, and construction began in July 1869. It ended a year

later, although the final tab skyrocketed to $250,000.

However, in a fairly short time, big problems emerged. The owners’

attempt to lure rich Southerners to the resort backfired, according to

Galloway, who wrote “this suggested limitation of patronage may have

contributed to its rapid decline since, in that period, the north grew

rapidly in wealth but the south made little progress in reestablishing

its financial status.”

Improved rail transportation may have also contributed to the Neff Resort’s

decline, since the hotel “received considerable patronage until the

railroads became more plentiful and people could go to other, more alluring

places,” according to Thompson.

Even more critically, the resort’s owners discovered that the structure

was built with green wood that, within an alarmingly short period of time,

began to warp. Soon, buildings became unsafe.

The house and its contents were put up for auction six times between 1872

and 1874 before the bids were high enough for a sale, said Mary Morgan,

a member of the Yellow Springs Historical Society. In 1874, the Neffs

were able to get the resort’s land back, but not the contents to

the house.

At the first auction, Morgan said, the Neffs hired someone to bid on their

behalf, but the man got drunk and missed his ride.

The Neff Resort’s decline bode poorly for all of Yellow Springs,

according to a 1881 article in the Cedarville Herald: “Yellow Springs,

without the Neff House and grounds, presents no attraction as a summer

resort . . . The village, with its college walls given over to dust and

vacancy and with its great Neff House and grounds seeded down to weeds

and cobwebs . . . with the general apathy and conservatism of the people

seems to be left to hopeless decay and general dry rot.”

The Neff House Park Summer Resort closed in 1882. It was torn down 10

years later.

—Diane

Chiddister

A

bit of mischief, a paper scam and (some) stability at Antioch College

Known to some outside

the community as the “infidels,” Antioch College was always

beset by financial uncertainty.

The school from its inception depended on the generosity of religious

donor groups to fund its operations, yet the charter under Antioch’s

first president, Horace Mann, required a commitment to a purely secular

education. No one benefactor, then, invested wholly in supporting the

school in perpetuity.

Yet 15 years after it opened Antioch carried on as always, interrupted

once again, and stepping to the off beat that gave it its reputation.

Because the Unitarians had raised the funds that saved the college from

its first dance with death when it closed for a year in 1864, Antioch

was considered for a period thereafter to be under their control, Robert

L. Straker wrote in “A Brief Sketch of Antioch College.” A good

portion of Antioch’s endowment was invested in government bonds and

then in Chicago real estate mortgages and timberlands in the Northwest.

Under the presidency of the Rev. George Washington Hosmer, a Unitarian

minister, the college was calm and marginally prosperous for a time. Enrollment

hovered around 220 students in the late 1860s and early 1870s. In 1869,

for instance, 55 college students and 82 preparatory school students were

enrolled. Around the same time tuition for room and board, classes and

books was $176.50.

In fact, Scott Sanders, the Antioch archivist, called this time “the

most boring period in Antioch’s history.” What made Antioch

boring, Sanders said, was its stability during the period, which Sanders

attributed to the fact that Antioch had an endowment, “capable administrators

and a fair number of students.”

But this stability would only last for so long.

The first issue of the Antiochian, the college’s alumni publication,

reported the year’s activities at the end of the 1869 school year.

Trustee John Cummings gave the college a new compound microscope that

magnified up to half a million times, the latest in technology at the

time. Five years later the school purchased a new lawn mower that was

drawn by one horse and that beautified the grass like no other.

Squibobs, an improvisational thespian group, made an uproarious showing

one year, as many of the students remained on campus during the holiday

vacation. Participants dressed in costume, assumed a fictitious identity,

and were implored at all cost to answer in the affirmative no matter what

the situation. According to the Antiochian, the spectacle invoked the

“menagerie and the circus,” and provided many hours of fun diversion.

Inevitably, however, boredom set in and students sometimes availed themselves

of destructive mischief. One group of “young men belonging to the

South Dormitory not having the fear of the law before their eyes, amused

themselves by having a chicken roast in one of the rooms.” The event

got out of control as the students began dancing and banging on all the

doors in the hall, and they were eventually ejected from the dorm.

In the mid to late 1870s, professor G. Stanley Hall was charged with investigating

a mail-order paper-writing scam originating in Yellow Springs. Headed

by William H. Hafner, an Antioch drop-out, the “Great Western Literary

Association” sold college-level term papers to students around the

country.

Antioch faculty issued a report on the association in 1876, calling it

a “gross and fraudulent” operation. Though Sanders said it is

not clear how rampant the scam was at Antioch, he said that the association

was a serious business, since two attempts were made on Hall’s life

during his investigation.

The faculty’s report, as well as an article in The Nation, helped

expose Hafner’s project, making his papers easy to detect.

Apparently the college’s reputation in Ripley, as a school that “uses

their powers to send their students to Hell,” a student said in a

1870 letter refuting outsiders’ impressions, was not completely unfounded.

Some no doubt had trouble accepting the coeducational philosophy, and

Antioch was one of the few colleges that accepted women. The school used

its tolerance as a drawing card. An advertisement that ran in the Yellow

Springs Review in 1880 read in bold letters, “BOTH SEXES ADMITTED.”

When Hall, founder of the American Journal of Psychology, came to Antioch

in 1872 after attending a men’s college, he commented on the coeducation

program: “I was always impressed with the way in which the strong

feminine element dominated the college sentiment, and felt that the active

boy student life that characterized other non-co-ed institutions was lamentably

lacking because of this.”

In 1875–76, Antioch established the Normal Department, “a course

to embrace the history of education methods [and] the modes of teaching

the advanced branches of the college to the lower classes.” The following

year 58 students were enrolled in the teacher training program, known

as the Ohio Free Normal School, which offered one year’s tuition

for students intending to teach at least one year after receiving a diploma.

However, during this decade the “Panic of 1873” had shrunk real

estate values, and the ensuing reduction in rents and interest rate dividends

hurt the college’s investments. According to the 1880 Antiochian,

property investments would not bring more than 50 percent of the original

amount of purchase.

In 1877, trustee Murry Nelson was already appealing to the alumni, family

and friends of the college that “unless they put their shoulder to

the wheel, Antioch could not be maintained on the small number of students

it has now.” The next year the Antiochian reported that the college’s

finances were a “matter of deepest concern” and that “Antioch,

as well as other institutions, feels severely the pressure of the times.”

That Antioch reportedly had the third highest endowment among colleges

in Ohio tells the state of affairs for private schools in general. Antioch

faculty salaries suffered because the college refused to go into debt,

and their meager $1,500 yearly incomes were further reduced by $300 to

subsidize operating expenses.

Furthermore, in an agreement between the faculty and trustees in August

1880, Sanders wrote in “More of the Glorious, Spurious, Hilarious

History of Antioch,” faculty were to pay for the coming year’s

course catalogue and maintain campus facilities. In return, they were

allowed to “raid the Antioch woodpile for their stoves.”

Needless to say, many professors soon left their positions at the college,

and the next year’s enrollment dropped to 12 students, Sanders wrote.

After commencement in 1881, the Antioch trustees voted to suspend the

college for the coming year, prompting the Cincinnati Gazette to later

print the headline, “A College Gone Begging.”

But before the year was out, the “citizens of Yellow Springs met

and declared this should not be,” the Antiochian reported in 1882.

The Christian denomination and the college trustees negotiated throughout

the year and decided a group called the Christian Education Society would

reopen the college in the fall of 1882 if they could have input in administrative

decisions.

With Christians strongly influencing the school’s progress and the

Rev. Daniel Albright Long serving as president of the college from 1883

to 1899, Antioch turned out more students seeking positions in the ministry

than in any other period of its history.

—Lauren

Heaton

Antioch’s

’69 baseball team

|

|

Members of the 1869 Antioch baseball team: front

row, from left: Hod Frost, RF; Thad Carr, C; Hugh Taylor Birch,

P; H. Elliott, 3B; and Dan Stone, LF; Cliff Bellows, 2B; Sam Beals,

1B; Matt Corry, CF; and Edward Felthausen, SS.

|

Antioch’s base

ball team falls to the Red Stockings –– that’s right, Antioch

had a base ball team, in 1869.

Heading in to the final inning of play on May 15, 1869, players on the

Antioch College base ball (that is how they spelled the national game

back then) team found themselves down by only 20 runs, not that bad considering

their opponents were the Cincinnati Red Stockings, the first professional

base ball team in history. Led by pitcher Hugh Taylor Birch, the Antioch

Nine finished the game on the wrong end of a 41–7 trouncing at the

site of what is now the Grand Union Terminal in Cincinnati.

According to the game’s box score, the Antioch’s student team

was outhit 27 to 12. Because no existing description of the game details

the defensive effort by either team, it is unclear how the team that became

the Cincinnati Reds scored 14 more runs than they had in total hits.

A local newspaper article also describes the Red Stockings as having a

poor day at the plate, despite the 34-run final advantage. Scott Sanders,

the Antioch University archivist, said that the Red Stockings were impressed

by Birch’s pitching, but Red Stocking infielders George Wright and

“Innocent Fred” Waterman were the game’s only true stars.

Each player scored eight runs and was thrown out only once during the

entire game. Antioch’s Arthur Elliot of Miamiville, led the Nine

with two runs, and reached base three times.

A newspaper account of the game described Antioch’s team as wonderfully

improved and better dressed than they had been in exhibition games the

previous year. The paper describes the “Antiochs” as well-built,

tall and “in every aspect perfect gentlemen.” The Nine also

drew quite a bit of attention that day with their new uniforms. A famous

Cincinnati photographer found their all-gray attire, adorned with an Old

English “A,” so attractive that he had them sit for a photograph.

According to local historians, the game was, for much of the 20th century,

incorrectly referred to as the first game in professional baseball history.

In a 1983 article in the Journal of the Society of American Baseball Research,

Antioch alum Dan Hotaling explained that the game was actually a preseason

contest, the fifth the Red Stockings played before beginning a national

tour as the first team to pay all of its players. Antioch was scheduled

to host the first game of this professional tour on May 31, 1869, but

pouring rains and an unplayable field kept the Red Stockings inside the

Yellow Springs House until they left for Mansfield, where they would go

on to win the first professional regular season game 48–14.

So, while Antioch wasn’t a part of the first professional baseball

game, the college does hold claim to hosting the first ever rainout of

a professional ball game.

Not much is known about what became of the young men who took the field

for Antioch that day. According to Sanders, Birch never graduated from

Antioch. Even without a degree he went on to be the general counsel for

Standard Oil, making a fortune that allowed him to purchase and eventually

donate the land that is now Glen Helen. Thad Carr, Birch’s battery-mate,

went on to own and operate a piano business in Springfield. Left fielder

Dan Stone became a math professor in Peru.

The rest of the team led a path that countless baseballers have traveled

since. Theirs was the path that begins with a photograph, capturing a

youthful love for a youthful game, and ends in quiet anonymity, with faded

memories of every “first” game and the ghosts of rainouts.

—Brian

Loudon

WCTU

battled the ‘nurseries of crime’

|

|

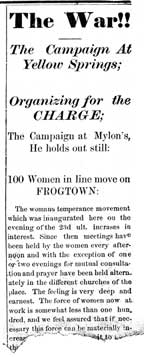

The headlines, above, were published over an article

on the local temperance movement in the ‘Yellow Springs Ledger’

on March 7, 1874.

|

In the decade following

the Civil War, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union fought its

own battle against the “Demon Rum.” The power of prayer pulsated

with particular vigor in Xenia, where the temperance movement in America

began.

Whether the tavern keepers of Yellow Springs knew it or not, they were

dancing right outside the lioness’s den.

Alcohol consumption during the early 19th century was on a quick trip

to the highest level in American history, leading one historian to refer

to the period as the “alcoholic republic,” Robert Kennedy wrote

in Harper’s Weekly. Temperance advocates in many states were lobbying

for prohibition laws, and by 1869 the Independent Order of Good Templars

had grown to 400,000 members.

In December 1873, after a temperance rally in Hillsboro, 70 women rose

from prayer at the Presbyterian Church, marched down to the saloons and

settled in on their doorsteps, singing “Give to the Winds Thy Fears.”

“Every day they visited the saloons and the drug stores where liquor

was sold. They prayed on sawdust floors or, being denied entrance, knelt

on snowy pavements before the doorways, until almost all the sellers capitulated,”

Helen Tyler wrote in Where Prayer and Purpose Meet.

Based on this model of peaceful resistance, two months later temperance

advocates in Xenia managed to scare 13 saloon owners in three weeks to

close their doors voluntarily.

In March 1874, the Yellow Springs activists got their turn. Women in the

village organized meetings every afternoon at alternating churches. They

circulated petitions among local citizens against the sale and consumption

of alcohol and expressly sought the signatures of physicians, druggists

and saloon owners, who were essentially the gatekeepers to the evils of

the drink.

Then hearing of the influential methods of imposition employed in surrounding

towns, the Yellow Springs Ledger reported on March 7, 1874, women descended

on a saloon owned by William Moylan and sang hymns in the name of purity

and abstinence.

Thus began the Temperance Crusades of 1873–74, which succeeded in

driving liquor out of 250 communities mostly in Ohio, but also in New

York, Michigan, Illinois and Indiana.

The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union was established in Cleveland

in November 1874, and the Greene County chapter organized in Xenia a year

later in February, according to M.A. Broadstone’s History of Greene

County, Ohio.

Six years later when the Yellow Springs Review was started, the Yellow

Springs chapter of the WCTU was submitting its own announcements to gather

public support for prohibition legislation. The Ohio Anti-Liquor Alliance

had organized in Columbus in 1880 to “crusade the state legislature

for a stringent ‘Local Option Law,’ ” giving townships

the right to decide their own laws concerning alcohol consumption.

An item in the Review urged clergy of all denominations to preach about

the issue to herald the arrival of petitioners coming to gather local

signatures. “Let the people make an earnest, united, persistent effort

this winter to release our beloved state from the cruel oppression of

the Rum Power,” the appeal said.

Right next to the announcement sits an advertisement for Chas. Ridgeway,

the local pharmacist at the corner of Xenia Avenue and Corry Street, selling

drugs, chemicals, brandy, wines, and liquors, “for medical purposes

only.”

The next week in the Review the union called itself the WCTU of Miami

Township and pushed more urgently for support.

“The greatest weapons against rum are the prayers of the righteous

and — the ballot box,” the group said in an announcement. “Five

nurseries of crime in one village are just five too many. Awake! And go

to work in earnest to promote the temperance cause.”

Even the Antioch College “infidels,” as the students were known,

strictly prohibited the use of alcohol on campus during the time. The

school’s laws and regulations in the 1870s stated clearly under general

conduct code number 29, “students who shall be convicted of having

in the College Buildings, or of using, except by order of a physician,

intoxicating liquors, shall forfeit their membership in the Institution.”

The goal of the women’s crusade had at its core “protection

of the home” and strived to keep the family intact. The WTCU’s

agenda to keep prohibition at the legislative forefront gave the organization

political clout that eventually worked to ratify the 18th Amendment in

1919, making the manufacture, transport and sale of alcoholic beverages

illegal.

Locally, the goal to prohibit alcohol consumption succeeded in 1905 when

Yellow Springs residents voted 197–175 to close local establishments

selling alcohol.

—Lauren

Heaton

Installment

1: 1803 to 1853

Installment 2: 1853 to 1868

Installment 4: 1883 to 1898

|