|

|

Installment

4: 1883 to 1898

|

|

Photo Courtesy of Antiochiana

The American Hominy Flake Co. was located near Xenia Avenue and

the railroad tracks during its brief time in the village. Downtown

Dayton Street can be seen in the background of this photo, which

was taken some time after Hominy closed.

|

The

brief, and flaky, life of Hominy cereal company

It may be that Thanksgiving Day, 1890, marked the high point of the American

Hominy Flake Company’s short-lived reign as producer of Snow Flake,

the village’s most famous food export and perhaps the world’s

first prepared breakfast cereal.

On that day, the Hominy Flake band performed an outdoor concert to celebrate

the company’s award for a “superior” food item at the recent

National Food Exposition held in Philadelphia, the Yellow Springs Review

reported on Nov. 21, 1890. Company founder William Little had visited

the exposition, bearing samples of Snow Flake cereal, manufactured in

Yellow Springs.

In honor of the award, the Hominy Flake band performed the “Hominy

Flake” Grand March, and, according to the article, H. Adams gave

a trombone solo and the audience heard a Watson serenade the titled, perhaps

appropriately, “Sweetly Dreaming.”

And while orders streamed in for the new cereal, the company’s success

blazed in other ways as well. The Review said that “a new dynamo

of 100-light power will soon be in use in the Hominy Flake works, and

wires will be run into the new hotel for the purpose of furnishing light

to the large number of summer visitors which we expect to entertain.”

After the company incorporated in June 1890, business took off like gangbusters.

The Review reported only two months later that “the increasing business

of the Hominy Flake company requires a more abundant supply of water for

their mill and pipes are to be put down.” A month later, the newspaper

stated, “The constant increase in the demand for Snow Flake Hominy

has necessitated the purchase of a larger engine and boiler by the company,

more than double the capacity of the one now in use.”

The American Hominy Flake Company, located at the current site of Peach’s

Grill, 104 Xenia Avenue, rode the wave of a natural foods boom in the

1890s, according to local historical Don Hutslar, who said the flakes

were probably not marketed at the time as breakfast food, but rather as

a healthy snack.

An October 1890 Review article stated that since June the company had

produced more than 2.75 million pounds of the product. A full train-carload

of Snow Flakes had just been sent to California, the newspaper reported,

and other cars were bound for Texas, Georgia, North Carolina, Colorado

and Wyoming. The California-bound train was decorated with a “very

appropriate streamer indicating the contents and the name of the company

manufacturing the article,” the Review reported.

There were glitches, of course.

“The incandescent electric light in use at the Hominy mill, is quite

a novelty for Yellow Springs,” an Oct. 24, 1890 Review article said.

“As soon as some further improvements shall be made, it will work

more satisfactorily.”

“The Hominy Flake mill has a new and more melodious whistle,”

the Review reported.

Overall, the company led the way for what seemed a period of unlimited

prosperity.

“With the Yellow Springs House in full operation and crowded with

guests, the Hominy Flake Company operating their works to full capacity,

and the buggy works turning out the latest style rigs, the lower end of

Dayton Street will present a lively appearance this summer,” the

Review said on March 13, 1891. “Yellow Springs people are to be congratulated

upon the possession of such lively progressive and energetic business

men.”

However, like some other Yellow Springs flakes, the American Hominy Flake

Company eventually came to ruin.

The first sign of trouble may have appeared in a June 16, 1893, Review

article reporting that James Currie of Springfield had filed suit against

the company for $18,000, which, he claimed, the company owed him for his

hominy flake patent. The paper reported that the judge in the case decided

in favor of Currie, and that when the new owner attempted to reopen the

plant he had “considerable trouble in getting hold of the machinery.”

Finally, on Oct. 27, 1893, the Review stated, “The machinery of our

Hominy Flake mill is being torn down and loaded on cars for shipment to

Indiana. When this mill was in operation it furnished work for quite a

number of persons. We are sorry to see it go.”

—Diane Chiddister

Opera

House also served as the community hall

|

|

Photo Courtesy of Antiochiana

The Village and Miami Township governments worked together to build

the Yellow Springs Opera House in 1890.

|

If you had a bird’s-eye

view of Yellow Springs on a warm spring evening in the early 1890s, you

might have seen men and women from all parts of town dressed in their

best dresses and suits making their way to the corner of Winter and Dayton

Streets, the site of the Yellow Springs Opera House.

Over and over again villagers flocked to the Opera House, where they were

entertained by minstrels, plays, Uncle Tom shows and lantern-slide shows,

or mobilized by temperance speakers to fight the demon rum.

One of the tallest buildings in town, the three-story Opera House was

“the image of many others scattered through the towns and villages

of Ohio and Indiana.

The buildings all have massive facades in the brewery-Gothic style, elegant

auditoriums, with seats that are decorated with elaborate iron fretwork,”

Paul H. Rohmann wrote in an article on the opera House, “Wig, Mask

and Hunting License,” which appeared in a 1954 issue of The New Yorker.

If you visited the Opera House on May 6, in 1892, you would have seen

“A Demorest Medal Contest,” according to that day’s issue

of the Yellow Springs Review. The evening included a flute solo, a prayer

by the Rev. H.C. Middleton, a vocal solo by Stella Tufts and, competing

for the medal, an assortment of prohibition speakers, including Ollie

Cox addressing “The Bible and the Liquor Question,” Hattie Sidenstick

speaking on “The Rumseller’s Legal Right,” and Gretta Berg

of Clifton discussing “The World on Fire.”

The next week’s paper announced that Berg prevailed, and took the

medal home.

A well-loved and much-used part of the Yellow Springs landscape in the

1890s, the Opera House was built in 1890 after a special act of the Ohio

State Legislature was passed two years earlier to allow the Township and

Village governments to jointly sponsor a $15,000 bond issue to finance

the construction of the building, the Yellow Springs News reported in

a special Yellow Springs centennial publication in 1956.

The Opera House served as the community town hall and was built as a multipurpose

facility for community events and administrative offices of both the Township

and Village.

However, like many other Yellow Springs institutions, the Opera House

was born in controversy. According to the News article, the rumor circulated

that after all votes had been cast on the bond issue, the vote counters,

who supported the construction project, announced the results by sticking

their heads out the window and shouting the win, then stuffing all the

votes into a nearby stove. There was no recount.

Controversy again stalked the Opera House in 1891, when a dance school

rented space in the building. An outraged letter writer said in the Yellow

Springs Review that dancing was morally wrong because “the anatomical

construction of woman does not permit her to engage in the violent exercise

of the dance without incurring severe penalties.”

While the dancing school’s fate is unclear, the Opera House prospered

during the next several decades. Activities in the Opera House in 1905,

according to a research paper by Keith Overton, included meetings of The

Farmers Club, the Veterans 44th annual reunion, the Grand Concert for

the Living Vine Club of Springfield (which cost 10 cents), the play Quo

Vadis, a performance by the Ithica Male Quartet, a concert by Olidence

and Houks Minstrels and a sermon on temperance by the Rev. G.D. Black.

The Opera House was the cultural center of the village and, in the 1930s,

housed both the Yellow Springs Summer Players and the Antioch Players.

About that time those groups’ performances became known for unannounced

visitations by the building’s full-time residents, bats.

“Along about the third or fourth play of our first season, a bat

made his stage debut and established a standard for appositeness that

no other bat, and few actors, ever equalled on that stage,” Rohmann

wrote.

“In the old stock favorite, Death Takes a Holiday, the character

Death was accompanied at his first entrance by a bat who swooped over

his shoulder, circled the stage, then darted out of sight,” Rohmann

said. “It was a masterly piece of dramaturgy — sharp, restrained,

authentic.”

However, subsequent bat appearances were less appropriate, according to

Rohmann. “If that bat had then been content to retire, all might

have been well. But, apparently stage-struck, he, or another like him,

had to keep coming back, whether it was his kind of scene or not. He fluttered

brazenly into a Park Avenue penthouse, zigzagged through one of O’Neill’s

tramp steamers, and blundered into boudoirs and barrooms, hospital wards

and prison cells,” he wrote.

After a while, according to Rohmann, the actors determined that, during

any given performance, there was a one-in-five chance of a bat appearance

and a one-in-nine chance that the bat would “distract the audience

with fancy flying.”

Taking the attitude that “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em,”

according to a later Yellow Springs News column by Louise Betcher, the

producers decided to mount a production of Dracula. However, during that

play’s run, not a single bat appeared.

—Diane Chiddister

|

|

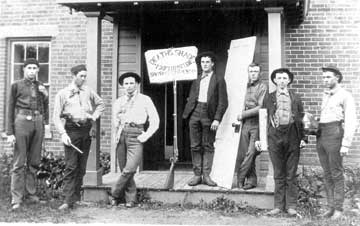

Photo Courtesy of Antiochiana

Top guns at Antioch, ca. 1884

Unidentified Antioch College students display firearms outside South

Hall, despite a regulation prohibiting guns on campus. The sign,

which says ‘Death’s Shade,’ possibly satirizes the

Latin mottoes students would give the many literary societies on

campus.

|

Yellow

Springs schools integrated in 1887

When the Union School

House opened in 1872, it was meant to house under one roof all the schoolchildren

in Yellow Springs. Everyone except for black children.

Most local black children weren’t publicly educated at all until

an African American school opened in 1871. Even in Ohio, it took legislators

22 years after the Civil War to get it straight, when the State approved

a law desegregating public schools in Ohio.

As early as 1804, the State began passing the Black Laws that edged away

at blacks’ civil rights, first to enter Ohio tax free, then to establish

residency and to vote. According to a student paper written in the 1960s

by Antioch college student Hugh Wylie, by 1831, blacks were prohibited

by law from attending public school.

Meanwhile, at the beginning of the 19th century, the public school system

was fragmented at best until 1825, when Miami Township divided into four

school districts and relegated part of the tax fund for building schools.

That year the first school in the township was built on Clifton Pike,

which today is State Route 343, after which 10 others gradually sprouted

in other districts in the village and the township.

In 1853 the Ohio legislature passed a law requiring local school boards

to establish schools for black students when the number of black children

exceeded 30. Almost two decades later Yellow Springs established its first

school for black students on the south end of Dayton Street. Then in 1874

the school was relocated in the old village school on the southeast corner

of West South College and High Streets.

Wylie reported that the late News editor Kieth Howard recalled interviewing

a black woman who attended an all-white rural school on Bryan Park Road

sometime in the 1870s. Though technically it may have been illegal, exceptions

may have been made for a few black students in more remote areas. The

woman remembered being ignored by the other students at first. However,

she said she became imminently more popular when the other children saw

her prowess on the baseball field.

Things began to change for schoolchildren in the village around the time

of the Civil War. Under the leadership of Benjamin Arnett, a bishop in

the African Methodist Episcopal Church who served as a State Representative

from Greene County, the Ohio Unionist Party gradually began repealing

the Black Laws. Arnett, who lived in Wilberforce, introduced the bill

in 1887 repealing the last of the Black Laws that would make racial segregation

of public schools illegal.

Yellow Springs resident Lucy Wolford, who was a student at the Union School

House school in the 1880s, told Wylie, “I’ve seen Bishop Arnett

many times. When he got in a buggy there wasn’t any room left.”

A powerful black man representing a white constituency, Arnett got his

repeal passed on Feb. 22, 1887, but he didn’t stop there. He and

a Reverend Jackson traveled around the area educating communities about

the bill’s provisions. Jackson came to speak in Yellow Springs a

month after the bill’s passage, likely influencing local resident

Silas Wills to campaign throughout the village in support of the cause.

Several years before, Wills had been denied his right to vote, legally

given to blacks in 1870, and had bought property in the village with the

proceeds from a lawsuit he won against the State.

Still devoting energy toward equal treatment of blacks in the village,

Wills, on the eve of integration in town, went to all the black homes

urging parents to send their kids to the Union School House.

Many were afraid, his son, J. Walter Wills, told Antiochiana in an article

in 1964, but “Silas kept saying that the time had come when a man

had to stop being a Negro and had to become an American. Nobody can take

your children through the door of that school but you. If you don’t

do it now, you may never get the chance again.”

Wills said that on the first day of school in September 1887, his father

stood at the door and counted the number of black students that came.

All of them attended school that day, he said.

Wolford, who was white, and a black man named Will Henry, had slightly

differing memories as students during those early days of integration,

according to Wylie’s paper. Wolford recalled a general sense of incredulity

among Yellow Springs citizens that integration would actually come to

fruition. A.E. Humphreys, editor of the Yellow Springs Review, wrote an

editorial anticipating that some families would pull their students out

of the school in protest.

The paper published another editorial at the beginning of the school year:

“Young America’s fathers and mothers are watching this opening

with special interest and not a little anxious. The striking of the word

‘black’ from the Ohio Statutes has removed the obstacle that

prevented Colored children attending the White schools, but it did not

remove the prejudice that exists in the minds of white parents against

mixed schools. . . we can only hope for the best and see what we shall

see.”

But Wolford insisted that integration in the school happened without incident.

Boys and girls sat on opposite sides of the room. The boys played together

at recess, though the black girls played separately from the white girls,

she recalled. The boys shared a bathroom, but the black and white girls

had separate toilets.

“Don’t let anyone tell you we had trouble like in Little Rock

and those places,” Wolford said. None of the students left the school

in protest of the new arrangement, she said.

Henry recalled that on the first day of classes all the black children

were sent home because a local minister and two school board members were

protesting at the school.

He also recalled that black students had to sit behind the white students,

at the back of the room. But he concurred with Wolford that, in his memory,

none of the students objected so much that they had to leave the school.

Wolford’s husband, J.N. Wolford, a former editor and publisher of

the News, remembered hearing that Cedarville schools integrated smoothly,

except that the blacks were taught in a separate crowded room for several

years, according to Wylie.

Bessie Totten, the late curator of Antiochiana, remembered a cousin who

attended the Union School House at the time of integration had been stoned

by a group of black boys, and that there were some people who just didn’t

accept the change, according to Wylie. Some also felt that integration

put black teachers out of a job, and that mixed schools weren’t acceptable

unless black teachers were hired.

—Lauren Heaton

Early

downtown shops destroyed in fires

|

|

Photo Courtesy of Antiochiana

First published by the ‘Hustead News,’ this photo shows

the destruction of the May 6, 1895, fire, in downtown Yellow Springs.

|

During the 1890s,

several big fires devastated downtown Yellow Springs, destroying many

of the buildings that housed early local businesses.

The fires highlighted a serious problem for the village in the late 19th

century: It did not have a fire department, leaving Yellow Springs to

rely on bucket brigades, lawn hoses and help from Springfield and Xenia

to fight fires here.

Several early downtown businesses on Dayton Street were destroyed in a

fire on Nov. 6, 1891, though there is little information available on

the blaze. The fire did prompt the organization of a fire department,

but the department apparently did not last long, the News reported in

a special section celebrating the centennial of Yellow Springs in 1956.

That fire, however, was small compared to the one that hit Yellow Springs

four years later. The Yellow Springs Torch, which is a predecessor of

the News, called the fire a turning point in the village’s history.

“The big fire of Nov. 6th, 1891, which devastated Dayton Street,

has been eclipsed, and the conflagration of May 6th, 1895, will hereafter

be the historic point from which to reckon all other local events,”

the Torch reported on May 10, 1895, in a long article on the fire.

“The greatest conflagration that ever visited Yellow Springs came

in devastating fury last Monday,” the Torch said, “leaving in

its track a desolated mass of ruins, blackened chimney stacks, ghosts

of trees stripped of the fresh tender foliage of Spring, and yawning holes

filled with twisted and seared iron roofing and heaps of smoldering ashes

to mark the place where a whole block of buildings stood. . .”

Started around 11:30 a.m. in the Little Elevator, a large grain elevator

near Dayton Street and the railroad, the fire destroyed nine buildings

in one block “bounded on the west by Corry Street, east by Xenia

Avenue and the railroad, north by Dayton Street,” the Torch reported.

The destruction included a hotel, a grocery store, a livery stable, a

restaurant and the old Methodist Church building, which the Torch described

as the first structure “erected this side” of the Yellow Springs

Creek, around 1840.

Because the village did not have a fire department at the time, requests

were made to Springfield and Xenia. The Springfield squad was the first

to arrive, by rail, around 1:30 p.m., and Xenia firefighters got to the

scene about 15 minutes later.

Though the firefighters could not save the nine buildings, newspaper reports

indicate that the fire crews and others were able to keep the blaze from

spreading. They were also helped by the wind, which shifted the fire away

from the post office and Xenia Avenue. Antioch College students formed

a bucket brigade and passed 120 buckets of water “in less than no

time,” the Sun reported, helping to save “lots of property.”

Many items were also saved by villagers who piled the material in yards

and on the streets around the burning buildings. “Never was so much

done so well by both the men and women,” the Torch said about the

firefighting effort.

The cause of the fire was unknown, the Torch and the Springfield Sun reported.

The blaze caused an estimated $12,000 to $18,000 in damages, most of it

covered by insurance. The Torch reported that all the buildings destroyed

in the fire, except for a carriage factory, would be rebuilt.

On this fire’s heels came another large blaze that broke out on July

25, 1895, on downtown Xenia Avenue. The fire started in Adsit Bakery on

the east side of Xenia around 3 p.m., the Torch reported. The fire spread

both north and south down that side of the street, destroying about six

buildings, including the bakery, a hotel and an office on Glen Street,

according to the Torch.

A bucket brigade was able to keep the fire from spreading farther north

along the street. The “bucket men,” as the Torch called them,

with the help of the Xenia and Springfield fire departments, were also

able to save the Winters Hotel, which may have been located on Glen Street.

The Sun reported that the fire caused about $10,000 in damages.

In response to the two fires, the Yellow Springs council started debating

local fire protection efforts. But despite the tragic events, it appears

some were apprehensive about paying for protection.

A special election was held in August 1895 on a $7,000 issue to purchase

a fire engine and build a reservoir, but it failed, the News reported

in its 1956 special. Another special election was held a month later on

a plan to build a $23,000 waterworks, but it was also voted down. At the

same time, the council approved new building regulations to beef up fire

protection efforts.

Then in January 1896, another large fire broke out on Xenia Avenue and

Glen Street, destroying several houses. The Xenia fire squad refused to

help, while Springfield sent a crew by railroad car.

In an article on the fire, the Sun criticized Yellow Springs for its lack

of fire protection services. Carrying a headline that read in part, “Poor

Old Unprotected Yellow Springs Again Fire Swept,” the article said

that the village was “not protected by fire apparatus of any kind,

save several sections of lawn hose.” A few days later, several horses,

farm apparatus and 5,500 bushels of grain were destroyed in a barn fire,

according to the News.

The council purchased a hand-drawn chemical engine in February 1896. A

month later, a fire company was formed, and on April 19 voters approved

a $2,500 bond issue to purchase the fire engine and five water cisterns.

It was not until 1907 that the Yellow Springs Volunteer Fire Department,

which would later reorganize and become Miami Township Fire-Rescue, was

formed.

—Robert Mihalek

An

ex-slave, Gaunt started annual charitable tradition

|

| |

Though he was born

into slavery, Wheeling Gaunt was able to buy himself and two relatives

out of slavery and build an extensive estate, part of which he would donate

to the Village when he died.

Little is known about Gaunt’s life, so it’s unclear why he would

give the Village nine acres of farmland and start a tradition — the

delivery of flour and sugar to Yellow Springs widows — that continues

today.

In 1812, Wheeling Gaunt was born into slavery on a tobacco plantation

owned by a John F. Gaunt on the Ohio River in Carrollton, Ky. When he

was 4, Wheeling Gaunt’s mother was sold to a slave trader who was

headed south, and Gaunt never saw her again. Every day he worked in the

fields for his owner, harvesting the crop for his owner, drying the leaves

for his owner, planting the new tobacco seeds for his owner. But he had

a vision.

It is unclear how long Gaunt had to work or how much he made for “blacking

boots and peddling apples,” as local historian Phyllis Lawson Jackson

wrote in a research file on Gaunt. But somehow, after devoting 32 years

of his life to a man known as his master, he managed to save enough money,

$900, to buy himself out of slavery and on June 20, 1845, Wheeling Gaunt

was a free man.

As if the monumental task of purchasing his own freedom didn’t mean

anything unless he could share it with his family, he remained in Carrollton

to work and save money to purchase two other slaves. Because he was free,

Gaunt was able to move up the labor ladder, and he drove wagons as a teamster

and continued to work on others’ farms.

In April 1847, Gaunt paid N.D. Smith $200 for a 21-year-old relative named

Nick on condition that Smith was “not responsible for the health

or soundness of said slave.”

Three years later Gaunt bought his wife, Amanda, for $500. When he later

realized she was technically his property, he filed manumission papers

to set her free, Scott Sanders, the Antioch University archivist, said.

All the while Gaunt was amassing property throughout Carrollton. In 1847,

the same year he purchased Nick, he bought his first property with a home

on it. According to Sanders, by the time Gaunt was ready to move on, he

had acquired perhaps 10 properties, some in Carrolton’s commercial

district.

Even as a landowner, Gaunt was still considered by some to occupy a lower

rung in society. An 1850 national census report on Gaunt’s estate

lists two presumably white tenants ahead of the Gaunts themselves.

The family came to Yellow Springs some time in the 1860s, perhaps because

they’d heard of the racial tolerance of Antioch College or the community

of freed slaves Moncure Daniel Conway had brought to the village. Gaunt

built a two-story green revival brick home on a sizable property near

the corner of North Walnut and Dayton Streets. He then added three to

four small cottages and called them “Gaunt cottages.”

Gaunt was a pious man and a member of the Central Chapel A.M.E. Church.

He also supported the kind of education he himself likely lacked, donating

money to Wilberforce University and the Payne Theological Seminary. He

also ran for the Yellow Springs school board in February 1887, the year

racial integration occurred in the public schools.

At some point Gaunt acquired the tract of land on the south side of West

South College Street, just east of what today is called Wright Street,

and had it farmed.

And though little information about his activities in the last 30 years

of his life is available, he may have been known outside of Yellow Springs

because just before Gaunt died the Cincinnati Commercial Gazette ran an

article summarizing his newly formulated will and calling him “our

wealthy colored citizen.”

At 82, Gaunt fell sick with Bright’s disease. In January 1894 he

bequeathed his entire estate, estimated at a value of $30,000, to his

second wife, donating property to Wilberforce College. He also left the

nine-acre tract on West South College to the Village, stipulating that

proceeds from the rent be used to buy flour for the “poor and worthy

widows” in Yellow Springs.

According to a letter from a researcher named C.W. Boyer to the late Read

Viemeister in 1976, the Village council in February 1894 had to consider

a resolution to accept the conveyance of Gaunt’s land, which, according

to council rules, had to be read on three separate days in order to pass.

But Gaunt wasn’t showing any signs of recovering, and the council

members didn’t know how much longer he would live. One evening council

agreed to make an exception and read the resolution three times in one

night. It passed unanimously.

The Yellow Springs Torch, which during this period was also called the

Review and the Weekly Citizen, published numerous announcements around

the time of Gaunt’s death in May 1894. The Torch, which titled its

articles “Our Colored Folks,” said that Gaunt was “known

to every distinguished man of his race, from Fred Douglass to Bishop Payne,”

as one of our “most highly respected” and “noble, generous

and kind-hearted citizens.”

The paper also reported that Gaunt had so many friends from Wilberforce,

Springfield and Xenia assembled at his memorial service that Central Chapel’s

High Street church was “filled to suffocation.” Gaunt is buried

in Glen Forest Cemetery.

The year Gaunt died, on Christmas Eve as he requested, the Village delivered

69 sacks of flour to 23 of the most “needy and deserving” widows

among the 50 or more who applied. Though the management of Gaunt’s

estate caused the rent to fall short of an expected $90 that year, council

member George H. Drake donated $20 out of pocket to make up the difference

and allow an even distribution of flour among the recipients.

Years later the delivery was expanded to include sugar, and the Village

continues the tradition of delivering flour and sugar to all local widows.

In 1955, the Village named the land after Gaunt.

When he died the Review said of Gaunt: “Many wealthy men have died

in this community but none perhaps will be remembered so long and so gratefully

as Mr. Gaunt.”

—Lauren Heaton

Installment

1: 1803 to 1853

Installment 2: 1853 to 1868

Installment 3: 1853 to 1868

|