BLOG – Kafka – “reading Kafka will make you smarter”/monstrous exaggeration

- Published: December 17, 2015

Part II of an impromptu series about Kafka, his life, and the scholars dedicated to understanding the Kafka enigma.

According to academic research, reading Kafka makes you smarter. The University of British Columbia and the University of California Santa Barbara did a study in 2009 that showed that the ‘cognitive mechanisms overseeing implicit learning functions functioned more acutely’ after readers read Kafka’s short story “A Country Doctor.” In other words, the brain is more powerful after reading Kafka.

In the story, a doctor makes a house call in the middle of the night. He travels on horses of mysterious provenance and ends up in bed with the patient and the patient’s gaping thigh wound. A horse pops its head through the window and shrieks horribly, and the doctor crawls home. And these are just the highlights – clearly it is the stuff of unsettling dreams, and like unsettling dreams, the story’s perplexing imagery begs the dreamer to come up with some sort of meaning, and this search for meaning kicks your brain into high gear.

In the study, some participants were given the text of the story and some were given a re-written version of the story that made more logical sense. Both groups were then asked to do a grammar-learning task that involved finding patterns in strings of letters, and then to copy the strings and place marks next to others that followed a similar pattern.

“People who read the nonsensical story checked off more letter strings – clearly they were motivated to find structure,” said Travis Proulx, a postdoctoral researcher at UCSB and co-author of the research. “The key to our study is that our participants were surprised by the series of unexpected events [in the story], and they had no way to make sense of them.” But after reading a story in which something “fundamentally does not make sense,” the brain is going to respond by looking for some other structure in the environment. Hence, they strived to make sense of something else, the string patterns. But what’s more important is that those who read the story were actually more proficient in recognizing patterns than those who read the more “normal” version of the story, Proulx said. They really did learn the pattern better than the other participants did, he said, and so the lesson I am choosing to take away from all of this is that Kafka readers are brilliant.[1]

Suffice it to say, that’s an outcome I’ll happily stand by.

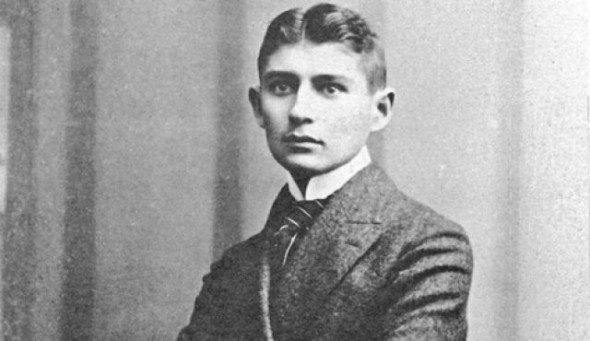

Although the above test seems to show that an active imagination can enrich the lives of others, academics and casual readers seem to think that because Kafka wrote stories like “A Country Doctor,” he was not a normal person. He had to be haunted, or at the least terribly morbid to compose something so frightening, and, as I mentioned last week, these assumptions color how his work is read. It seems an outdated and simplistic assessment, and as I also mentioned last week, modern scholars have done a lot to separate Kafka myth from reality. Modern understandings are much more in line with the Kafka that his friends, families, and partners knew – a polite, charming, and “obviously intelligent” man – but it seems that even this treatment of his life can’t exist without some embellishment.

In a 2008 book called Excavating Kafka, James Hawes, a British satirical novelist, does both of those things. The book paints a more realistic portrait of him and examines his interests and actions in a way that makes them seem much less abstruse; time and distance accord passing  interest in something a profound importance that may not actually be there. Kafka’s curiosity about Yiddish theater, for example, is portrayed as a something that interested him for entertainment, historical, and artistic reasons, in the same way that someone today is able to explore a casual interest without it necessarily reflecting some deep psychological rupture or identity crisis. Naturally every interest says something about one’s subconscious, but his point is that the Kafka mythos endures because it feeds on its own assumptions, clouding true understanding.

interest in something a profound importance that may not actually be there. Kafka’s curiosity about Yiddish theater, for example, is portrayed as a something that interested him for entertainment, historical, and artistic reasons, in the same way that someone today is able to explore a casual interest without it necessarily reflecting some deep psychological rupture or identity crisis. Naturally every interest says something about one’s subconscious, but his point is that the Kafka mythos endures because it feeds on its own assumptions, clouding true understanding.

Kafkalogy’s old guard may have been reticent about but ultimately capable of coming around to the new perception of Kafka had Hawes not made an enormous fuss about the supposedly astonishing information he uncovered and featured in the book. His information, he said, was so scandalous that it would change our perception of Kafka forever. Kafka fans held their breaths for the book’s publication. Finally, the big reveal: Excavating Kafka details (what Hawes claimed was) Kafka’s use of “pornography” and rampant sexuality. Hawes said Kafka subscribed to upmarket porn and went to brothels.

The book was released to a storm of controversy. Mention of “Kafka’s pornography” featured into all coverage of Excavating Kafka. Hawes’ portrayal Kafka as some kind of lubricious maniac was considered a corruption of their prophet, or so the media made the reaction out to be.

While I understand the serious academic debate new readings of a topic engender, I can’t help but roll my eyes at the book’s obvious marketing ploy and the completely exaggerated claims made by Hawes. (Not to mention that the real debate in Kafka scholarship was primarily with the broader conceptual changes mentioned above. Excavating Kafka’s genuinely awesome treatment of these topics was totally overshadowed by the sensationalism of the sex obsession.)

In reality, Kafka’s “porn” amounted to strange illustrations in a literary magazine he subscribed to called “The Amethyst,” and his rumored satyriasis was based on rumors that he visited brothels. The illustrations were, at their most realistic, nudes appearing to be from an artist’s sketchbook, or, at their most frequent, kind of odd, like a frog interacting with a certain something growing out of a flower. Were the images sexual? Yes, in that they featured a depiction of something related to sex. Did Kafka have a pornography obsession because a literary magazine happened to feature drawings of animals with oversized units amid slightly racy poems and stories? No. Does this mean that Kafka exhibited an unusual or all-consuming obsession with sex? I guess it depends on the motivations you want to ascribe him, and where it falls within the boundaries of relative morality, but I will venture a guess and say that no, it does not.

Whether sensational new claims or stodgy old perceptions, people seem to have a hard time accepting that Kafka was just a regular guy. He lived to pursue his hobby, he hated going to work; he had issues with his family, he went out with his friends. He had lovers and long term relationships; he liked to exercise, he loved to read; he was afraid of commitment but very caring, and he made excuses for himself, because, like many people, owning up to his true feelings and telling them to the person they are certain to hurt is much more difficult than waffling around forever, which seemed to be his tactic for a while.

Kafka was, at the heart of it, a personable, sensitive, fastidious, and enormously talented human being – this evidently hard-to-process combination has stymied scholars for years because they can’t reconcile the dynamism of Kafka’s person and imagination with the fact that he was capable of existing as a regular, flawed human, beset by relationship problems, an overbearing dad, and the annoying necessity of working. Divorced from all fanciful notions, Kafka exhibits all of the qualities of a pretty standard young man. Given the weight accorded to Kafka’s thoughts and behaviors, how many other people alive, then and now, might be elevated to Kafka’s status for the same reasons, were they only to write some unusual fiction?

Tune in soon for the final installment of this series, in which I discuss an American Kafka scholar’s incredible contributions to Kafkalogy. Profound love, a lost cache of priceless documents, narrow escapes, and a globe spanning treasure hunt – NEXT!

[1] The universities conducted a second study to test this hypothesis. People were made to consider how their past actions are often at odds with the consistency they accord themselves. The second test elicited the same results as the first. The subjects were better able to replicate the patterns in letter strings after experiencing something that doesn’t seem to make sense: humans, when confronted with the truth that they aren’t the bastions of logic and consistency they think they are, are so baffled by this contradiction that their brains go into overtime trying to make up for it by finding more stable patterns in the world.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.