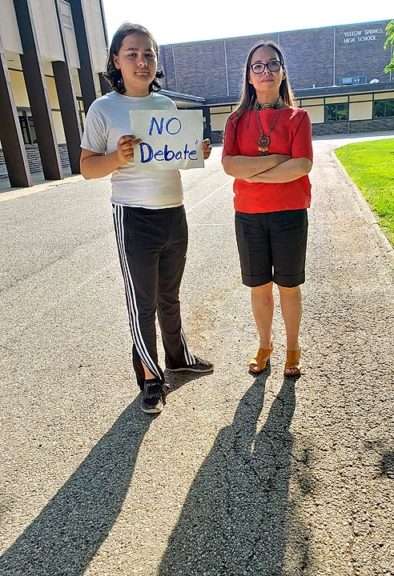

Jennifer Knickerbocker and her son, McKinney eighth-grader Theo, stood in protest of a planned debate in a Yellow Springs High School 10th grade social studies class in which students were to argue for and against the use of Native American names and imagery for sports teams. The debate was canceled this week and students were given a new assignment, while YSHS/MS is developing plans to expand its coverage of indigenous issues and perspectives in the future. (Submitted Photo)

Native American mascot controversy— Schools learn limits of debate

- Published: May 30, 2019

There’s the Cedarville Indians, the Wayne Warriors and the Wapakoneta Redsk—s.

Should schools use Native American images and names for sports teams?

Yellow Springs High School 10th-grade social studies students were set to debate the pros and cons of that question next week before a panel of community member judges.

But over the last week, YSHS staff, school parents and villagers wrestled with a different question — should the issue of Native American mascots and nicknames be up for debate?

To villager Jennifer Knickerbocker, who is Anishinaabe of the White Earth Nation, the answer to that question is a clear no.

“The debate is long over,” Knickerbocker said, citing, for one, the U.S. Commission on Human Rights ruling on the issue, which called the use of such mascots insensitive, disrespectful and offensive.

“They are particularly inappropriate and insensitive in light of the long history of forced assimilation that American Indian people have endured in this country,” the commission ruled in 2001.

Knickerbocker also urged the school to cancel the debate because of the possible trauma it might cause her son, who is in the class. She said he was upset by the planned debate, especially since he could have been assigned the “pro” side of the debate.

To Knickerbocker, that students would debate the issue without hearing an indigenous perspective on the matter was wrong.

“Teaching people that you have a right to debate this issue without representation of Native Americans on the issue, is an underpinning of white supremacy,” she said.

Several other villagers shared their concerns in emails sent to YSHS administration and the class’s teacher, Kevin Lydy, over the last week.

Finally, 10 days after the debate was announced, YSHS principal Jack Hatert made the decision to cancel it on Sunday, May 19.

Hatert said that upon reflection, moving forward with the debate would be wrong because of its potential for harm.

“It’s important that the intention was never to be hurtful or harmful, and when we recognized that it would be, we had to make a change to do what’s right,” Hatert said this week.

“It’s not a topic that should be debated,” Hatert added. “Reflected upon, discussed, but not debated.”

Lydy explained that the debate was to culminate a five-week unit on the struggle of Native Americans for equality, a curriculum that included resources on Indian removal, boarding schools, the Wounded Knee Massacre the American Indian movement and more.

Lydy said it was his intention from the beginning to show that the “pro” side of the argument was an indefensible position.

“To me the evidence is overwhelming [against the mascots],” Lydy said. “The debate was meant to enlighten those issues.”

Debates can be useful as part of an inquiry-based method of teaching in which students come to the conclusions themselves, Lydy added. But he also understands that hosting a debate might legitimize the “pro” side, which is why he agreed to cancel the debate.

“It would provide a venue — a forum — for people who support Native American mascots,” he said. “We heard members of our community voicing opposition, saying that mascots are dehumanizing, and we want to be receptive to that.”

Hatert believes the experience was a moment of learning for all involved, and a demonstration for students of right action.

“Canceling this debate is modeling for our students doing what is right and it is the first step in empowering them to take appropriate action,” Hatert wrote in an email. He added that feedback from the community has helped him and Lydy “grow as people and as educators” and apologized for “any pain and trauma the planned debate may have caused.”

After sending numerous emails to YSHS staff, speaking with Lydy in person and considering a federal Title VI civil rights complaint against the school, Knickerbocker was relieved that the debate was eventually canceled, saying she’s glad the school “took a pivot in the right direction.”

“This was the perfect example of marginalized voices coming to together to say, ‘don’t do this,’” she said. Knickerbocker is now hopeful that the schools do more to engage indigenous people who live in the area.

“For far too long Native Americans and Indigenous people have been invisible and this is the central issue,” she wrote in an email.

This week, those who weighed in about the debate spoke to the lessons learned and next steps to bring indigenous perspectives and awareness of the issues they face into the local schools.

The debate proposed

It started with an email YSHS history teacher Kevin Lydy sent on May 10 to community members to ask them to judge an upcoming debate. He reached out to some villagers with Native American heritage to serve as judges, including Knickerbocker, Shane Creepingbear, who is a member of the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma, and Sommer McGuire, who is Puerto Rican with indigenous ancestry.

Students would be assigned “for” or “against” positions on the issue, while judges would assess the students’ debate presentations, score them, and provide “constructive feedback to the students on their performance,” Lydy explained in an email.

Lydy said in an interview that he chose the mascot issue for the debate because it would allow students to see issues concerning Native Americans “right next door.”

“For students, it’s an entryway into the larger issue that people think [Native Americans] only exist in history,” Lydy said.

Lydy added “right next door” means the Cedar Cliff School District, which goes by the name Cedarville Indians and uses for its logo an image of a Native American man in profile wearing feathers.

According to a 2018 Dayton Daily News article, there are 19 schools in the region with Native American nicknames and imagery. For instance, the Stebbins Indians (Riverside) and the Wayne Warriors (Huber Heights) use logos of indigenous males in headdresses. The Lebanon Warriors’ slogan is “Fear the Spear.” And the Piqua Indians’ student-run TV station bills itself “Indian Nation Station.” North of the Dayton area, schools in Wapakoneta, Fort Loramie and St. Henry still use the racist slur “redsk—s” as their nickname.

Ohio is ranked either first or second in the nation for the use of Native American mascots in high school and college sports teams, according to various sources, with more than 200 public schools in Ohio still using such mascots and nicknames, according to a Cincinnati Enquirer article last year.

The debate opposed

On the same day that Knickerbocker received the email, she responded to Lydy to say that she could not participate as a judge and asked him to not continue with that debate topic.

“The imagery and stereotypes have real and dangerous consequences for me and my people and it’s been proven that the epidemic of abuse of Native people is inseparable from these stereotypes,” Knickerbocker wrote. “I and other Native people have a lot of trauma related to these mascots and feel powerless, tokenized and mocked.”

In her initial email, she drew a parallel to an issue concerning African Americans.

“One would not ask a black person to sit in on a debate about blackface because, socially, this issue has been resolved as wrong even though the folks in Ohio haven’t caught up yet,” she wrote.

The American Psychological Association, or APA, has acknowledged the harm that Native American mascots can cause, calling for their retirement in 2005. According to the APA, when Native American youth are exposed to such “racial stereotyping and inaccurate racial portrayals,” their “social identity development and self-esteem” are harmed. The stereotypes also have an impact on non-indigenous people.

“The symbols, images and mascots teach non-Indian children that it’s acceptable to participate in culturally abusive behavior,” according to the APA position paper.

Last weekend, other community members weighed in too, including Creepingbear, who wrote that the debate would “give a platform for white supremacy.”

“I’m disappointed that after hearing the traumatizing nature of this topic you have chosen to move forward with this racist debate,” he wrote. “Moving forward with a debate on this topic signals to your students that an argument for racist mascots has validity,” Creepingbear added.

McGuire also sent an impassioned appeal on the debate over the weekend, saying that there is no “pro” position on the mascot issue and encouraged another topic such as pipelines, which has connections to issues such as environmental racism, tribal sovereignty and missing and murdered indigenous women.

McGuire also relayed a frustrating experience as a judge of last year’s debates in the same class.

While McGuire was thrilled to learn of the class’ unit last year on the struggles of Latino-Americans and Asian-Americans, she bristled at the debate question — should English be established as the official language of the U.S.? As a Latina, it was “tough” to hear some of the arguments on the pro side.

“While it was heartening to see some students truly support diversity and inclusion by recognizing that people come to our country with language and cultural traditions that should be honored, it was tough to hear kids parroting the rhetoric of [President Trump] and the culture that this administration has created,” she said.

In the end, the “pros” prevailed in four of the seven debates, McGuire recalled, and she wondered whether the students learned much about the deeper issues of immigration, cultural assimilation and integration. She believes the debate may have done more harm than good.

“We need to not only be as impactful as we could be, we need to also not be harmful, because that is the last thing our kids need right now,” McGuire said. “There is already a lot of hurt out there. They shouldn’t find it in the classroom.”

The impact of the planned debate on her son was one reason driving her vocal opposition, Knickerbocker said.

“Watching how this has impacted my son has been hard,” she said.

The debate canceled

Knickerbocker was relieved the debate was canceled. But this week she also expressed frustration at the slow pace of change in the state. Since moving to Ohio a year and a half ago, Knickerbocker has had a difficult time with some prevailing attitudes toward indigenous peoples. Because there are so few indigenous people, they become “invisible,” she said.

“Ohio is a hard place to live for a Native American,” she said. “I have felt very out of place.”

A 2014 analysis by FiveThirtyEight found that Native American “mascoting” is more prevalent in states where fewer Native Americans live. Ohio has no federally recognized Native American tribe and a native population among the lowest in the nation — at 0.3 percent, according to U.S. Census data — after most Native Americans were forced to leave the state in the 1800s.

When the school didn’t immediately decide to cancel the debate, Knickerbocker reached out to several colleagues and students at Antioch College, where she works as the director of foundation and corporate relations. A group of Antioch students said they would protest, while some instructors and administrators provided support in other ways.

“When you don’t have tribal representation, it’s helpful to have a gut check,” she said of reaching out to others on campus.

For example, Luisa Bieri provided the high school with resources that explained the differences between debate, discussion and dialogue. She wrote in an email to the News that at Antioch, several instructors are leaning toward dialogue over debate.

“The underlying values of debate reinforce supremacist thinking of ‘winning’ and ‘losing’ sides of an issue rather than working to acknowledge and understand differing viewpoints,” Bieri wrote.

Dialogue, by contrast, aspires toward “connection instead of competition” and emphasizes “deep listening, self-awareness and cultivating a sense of curiosity towards others’ lived experiences and perspectives,” Bieri added.

Antioch spokesperson James Lippincott weighed in on the role of those with privilege to “speak truth, and to stop the further spread of damaging bias, stereotypes, false narratives and racism.”

“I sincerely hope that this becomes a teachable moment for students at Yellow Springs High School — and for the community at large — about how privilege can cause us to not recognize the pain of others,” he wrote in an email.

This week, Hatert said the discussion has been a learning experience for all, including students. Although some students were looking forward to arguing the “con” side, others were relieved the debate was canceled in case they were assigned the “pro” position, Lydy said.

Hatert now wants the school to do more to cover indigenous issues.

“We do have a desire to do more to connect with the Native American people in Yellow Springs,” he said.

In addition to commemorating National Native American Heritage Month in November, Hatert hopes that indigenous perspectives can be incorporated into social studies curricula school-wide.

“I don’t love the idea of celebrating it for only one day,” Hatert said.

On Tuesday, Lydy and Hatert had lunch in Antioch’s Birch Hall with instructors of a relatively new course, Dialogue Across Difference, to learn more about their pedagogy, as well as to hear from Antioch staff and students who are indigenous.

To Knickerbocker, doing so is in line with Native American practices, and portends well for future collaborations.

“Sitting down to a meal together to talk about how we can collaborate for good is a very Native American way that we often call: the good way. … I am very happy that we are seeing each other and there is so much respect all the way around.”

After the meeting, the social studies students were given a new assignment. On Wednesday, they were to start drafting a letter to advocate for the removal of Native American mascots that will be sent to area school leaders, media or others.

“The students will have voice and choice regarding the recipient of their letter, based on whom they feel they will be able to impact the most,” Lydy wrote in an email.

“I feel this helps students end this unit with a sense of accomplishment and empowerment,” he wrote.

Contact: mbachman@ysnews.com

Comments are closed for this article.