BLOG — Book Round-up, part 2

- Published: November 12, 2015

A good way to decompress after reading a particularly weighty or involved tome is to read a good detective novel. Aside from the Detective Beck books by Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo, my choice detective books are the novels of Jonathan Kellerman. Although the books (and many like it) are arguably goofy, there is a lot more to them than a reader may realize. The technique is fascinating – what seems like a straightforward pulp story is actually something carefully calibrated to suck you in, and the subtleties of stock characters show the author’s attitudes to the grim issues often portrayed in the books.

In any case, what follows is an overview of one of Kellerman’s books, as well a bit about the annoying work that inspired me to take a break from needlessly pompous literature.

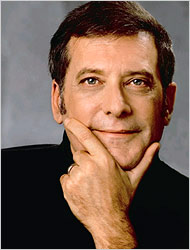

The first book of this column is the concisely-titled 2006 novel Gone, another stoic, monosyllabic entry into the thriller genre by perennial crime fiction author Jonathan Kellerman. The protagonist of most of his books is one psychologist-turned-sleuth Alex Delaware, and Kellerman’s academic credentials and years of practice as a psychologist seem to give Delaware voice a dose of legitimacy, in the same way that the novels of a former police officer or a former criminal prosecutor benefit from their authors’ respective experience. Kellerman authored heavy non-fiction tomes Psychological Aspects of Childhood Cancer and Helping the Fearful Child before his turn to writing fiction full time. Kellerman is known for his unending stream of murder mysteries (one, sometimes two, per year) as told through the eyes of the not un-Kellermanesque detective Delaware, who is similar to the author not just in appearance and presumed mannerisms. Kellerman writes what knows – the elements of psychological insight peppered throughout the books give credibility to the reader’s perception of Delaware as a psychologist, the verisimilitude heightened by an academic parlance the average reader would imagine criminal psychologists to use.

The first book of this column is the concisely-titled 2006 novel Gone, another stoic, monosyllabic entry into the thriller genre by perennial crime fiction author Jonathan Kellerman. The protagonist of most of his books is one psychologist-turned-sleuth Alex Delaware, and Kellerman’s academic credentials and years of practice as a psychologist seem to give Delaware voice a dose of legitimacy, in the same way that the novels of a former police officer or a former criminal prosecutor benefit from their authors’ respective experience. Kellerman authored heavy non-fiction tomes Psychological Aspects of Childhood Cancer and Helping the Fearful Child before his turn to writing fiction full time. Kellerman is known for his unending stream of murder mysteries (one, sometimes two, per year) as told through the eyes of the not un-Kellermanesque detective Delaware, who is similar to the author not just in appearance and presumed mannerisms. Kellerman writes what knows – the elements of psychological insight peppered throughout the books give credibility to the reader’s perception of Delaware as a psychologist, the verisimilitude heightened by an academic parlance the average reader would imagine criminal psychologists to use.

In this novel, fortunately bearing a much better title than cringe-inducing appellation of the first Kellerman book I read – Bad Love – two acting students (one of whom is bears the noteworthy and inspiring name Dylan) are found in the mountains of Malibu and claim that they were brutalized by some sadistic abductor. It is revealed that their abduction is a hoax, but it turns out that one of the two actually does get murdered. “A host of eerily identical killings” occur, and it is up to Delaware and best friend/grizzled gay cop[1] Milo Sturgis to figure out what “bizarre and brutal epidemic is infecting the city with terror, madness, and sudden, twisted death.”

With some background information helpful but not necessary, any book in the series can be picked up and be enjoyed as a standalone mystery or serve as an introduction to the world of Alex Delaware. This accessibility is reflected in Gone’s conventional-yet-comforting unfolding of events: in this particular installment of the series, almost everything that happens isn’t particularly surprising (or even noteworthy) and yet remains entertaining, in the same way that similar crime drama TV shows can suck you in until you know who the murderer is and if they get their comeuppance.

In reading this book and enjoying movies based around a criminal’s exploits, I’ve often wondered why something so terrible is so fascinating and fodder for cheap thrills. John M. Reilly, in the monster encyclopedia Twentieth Century Crime and Mystery Writers, assesses the difference between the fictional and truthful accounts of crime:

“The account of a crime in, say, a newspaper article contrives to establish raw fear of criminal violence. In other words the conventions of reportage function to diminish the distance between  readers and the threat of actuality. In contrast, mystery fiction thrills rather than threatens, because such motifs as the perversity of human invention when bent to violence, or the evident similarity of motives shared among likely suspects and the guilty, are contained within a design of plot in which we arealways sensitive to the author’s hand. Theme, event, character – all these affirm the literary form rather than reconstruct reality. Crime and mystery literature, thus, displaces the subject of violence with patterns of story-telling that, even in tales of mean streets, work against our receiving them as direct commentary on real life.”

readers and the threat of actuality. In contrast, mystery fiction thrills rather than threatens, because such motifs as the perversity of human invention when bent to violence, or the evident similarity of motives shared among likely suspects and the guilty, are contained within a design of plot in which we arealways sensitive to the author’s hand. Theme, event, character – all these affirm the literary form rather than reconstruct reality. Crime and mystery literature, thus, displaces the subject of violence with patterns of story-telling that, even in tales of mean streets, work against our receiving them as direct commentary on real life.”

The same could be said for true-crime books whose subjects are real but whose prose reads like the lurid, outrageous, violent parables and characters that form our cultural landscape. Are they fascinating because they are so rare, or because they are so commonplace?

Violent stories may seem less so because they are not considered close to reality, but even so, perhaps because of his actual experience as a psychologist, Kellerman’s books are noted for being relatively free of the deliberately ghastly, oftentimes exaggeratedly violent crimes that characterize other best-selling suspense fiction. Occasionally gory scenarios arise out of necessity, but given the author’s own admitted intolerance of violence, the brutality of the crimes is kept somewhat in check as to not seem overly sensationalized. Similarly, though crimes against children are a necessary component of detective fiction (and unfortunately not an unfair topic due to the fact that crimes against children do occur in real life), Kellerman doesn’t exploit his knowledge as a child psychologist to give his books that much more of a grim edge, or to create villains with a more developed aura of perversion.

Not that his books are PG, but they are kind of uncool. Kellerman’s books are narrated not with a show of gritty street slang or cool criminality but with the avuncular next-door neighborliness of a good family doctor. It’s exactly the tone that a professional and not too cool (but cool enough) bachelor would adopt, which is exactly what Delaware is. Dialogue that has the obligation of capturing the tough, sexy, manipulative, and/or vindictive voices of the rough-edged people that populate the novel comes across like a not-tough guy trying to write really tough characters. Consider these lines:

“I passed out. Maybe I’ve got a concussion.”

“Your head was stationary and if you had a rudimentary knowledge of neuropsych you’d know that severe concussions result most often from two objects in motion colliding.”

and

“You into fishing?”

“I’m into eating.”

“Virtually the same, huh? said Marcia Peaty. “More like twins than cousins.”

“Cousins can be real different.”

Obviously the storytelling is sometimes unintentionally amusing; the prose is “effective but hardly memorable,” as one detective fiction encyclopedia notes in its entry for Kellerman. Nevertheless, they are fun criminal romps, and the prose reminds the reader of this. The detachment comes not from being inured to violence but because the writing doesn’t make this the forefront of the experience.

Are Kellerman’s books dispensable tales for the beach, as more “sophisticated” readers maintain? Or are they actually deep sociological meditations on authoritarianism, poverty, sexuality, and violence? Are the prerequisites of crime fiction a “public sympathy for law and order and the creation of official police,” and is a bootlicking reliance on authority furthered by novels of this sort? Or are books such as Kellerman’s, and those of many other million-selling thriller writers, simply entertainment? For all intents and purposes, it is irrelevant: whether guilty pleasure or legitimate entertainment I make no judgment, as I operate under the simple credo that a good library is a varied one.

[1] The only reason his “orientation is pointed out is because casual readers seem to note its (unusuality), but in reality, a fictional gay detective is nothing out of the ordinary. “350 gay and bi sleuths appeared in novels, plays, and films over [a] fifty-two year period,” according to Drewey Wayne Gunn’s The Gay Male Sleuth in Print and Film, but it may be of interest to note that Milo Sturgis was the first openly gay police detective to appear on TV, as he did in 1986 in NBC’s adaptation of Kellerman’s first novel When the Bough Breaks.

****

And speaking of Gone’s use of neologisms to both lambast and admit a resignation to the influence of culture (…), we come to a seminal twentieth century novel by Witold Gombrowicz. “To irritate, Gombrowicz seems to say, is to conquer,” says Susan Sontag in her introduction to the Polish classic Ferdydurke. The extent of the conquering done through irritation is up for debate –  thanks to the books’ complex, playful, and somewhat obnoxious twists and turns the book has inspired much political and critical controversy, and has been equally panned for this reason as well.

thanks to the books’ complex, playful, and somewhat obnoxious twists and turns the book has inspired much political and critical controversy, and has been equally panned for this reason as well.

It is well-known that Gombrowicz intended to deliver an irreverent thumb to the nose through Ferdydurke at the eternally snooty cliquishness that is the writers’ circle, the posturing of all artists, and the arbitrariness of Culture: one theme of the novel is a disjointed celebration of what is called ‘immaturity.’ It is not an immaturity of solely the childish kind (although this is certainly celebrated as well), but a kind of self-aware flaunting of the established rules of art and society.

The book certainly reads with derisive, playful abandon, like someone mocking experimental poetry by writing a poem chock full of haphazard line breaks or attempting to mock modern art by gluing a bunch of junk together and splattering it with paint, yet all the while holding some hope of success because they secretly believe that in their mockery, they too possess the same pretentious madness required to produce a successful work.

The book chronicles protagonist Joey’s return to adolescence thanks to the wiles of a Professor Pimko. Joey is placed back into a school yard where he is subject to various childish mockeries, games, and derisions (ie a funny-face battle) and as such has no choice but to become “immature” again himself. Couched in this is a lesson about “the nature of mechanisms that create one’s image and emerge from human interactions,” as Elwira Grossman notes, translating to a critique of any sort of social influence and thus socialized behavior.

The edition I acquired was the most recent translation by Danuta Borchardt, and much has been said of the expertise and accuracy of her translation, inasmuch as the playful language of the original can be translated. The original Polish of Ferdydurke is brimming with linguistic tomfoolery and any translation (almost by design) falls woefully short of the experience Gombrowicz intended. Unfortunately I am completely ignorant of Polish and so cannot appreciate or vouch for how well the linguistic games are transmitted via English, but it is sufficient to say that critics and scholars seem to be in unanimous praise of Borchardt’s accomplishment (and all the more so because the previous English translation was itself translated from versions of Ferdydurke in Spanish and French).

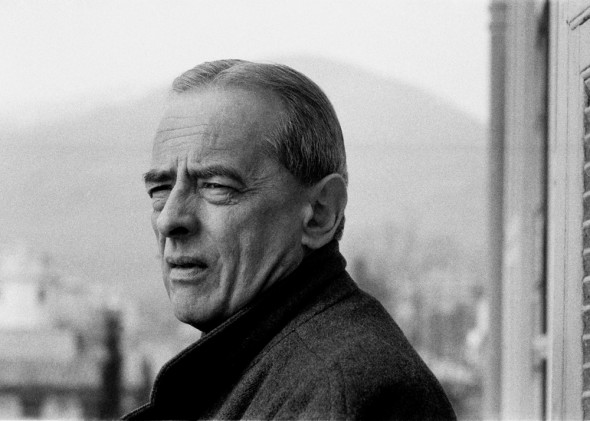

Gombrowicz fled Poland to Argentina as a correspondent on a pleasure cruise hours before it fell to the Nazis – he arrives, Poland falls, and he wasn’t able to return to Europe for twenty-four years. He lived in relative obscurity and penury in South America until his novels were rediscovered and subsequently re-banned in Poland in the years following World War II.

The novel was naturally banned by both Nazi and Communist authorities doubtlessly because anything beyond the comprehension of mindless government thugs is considered subversive: I am imagining a frustrated fanatical censor feeling that the book is mocking his intelligence, and as a revenge for confusing him he deems the author an enemy of the state. (More truthfully it was banned by the communists because Gombrowicz was the son of a rich landowner.)

An amateur scholar by the name of Christopher notes in an online discussion of the novel that “a novel about the debilitating influence of convention could hardly be conventional; it is idiosyncratic to the point of an obsession.” Granted, but is this always a worthwhile approach? Ferdydurke is one of those novels whose love-it-or-hate-it personality is an integral part of its being; many readers give up in frustration sixty pages in while others tout the enlightening rewards of soldiering on. The reader has to ask herself – do I need to read something so maddening to realize that the ‘normal’ conventions of real life are themselves maddening parodies of what life can actually be?

I personally can take only so much of this manner of critique. I appreciate the sentiment but am completely annoyed by the novel. Is that the point? Is the book done in a “new and revolutionary form” and is it really, as one critic notes hyperbolically, “a fundamental discovery”? Is the existence of the book, readable or not, a challenge to Culture in and of itself, despite or perhaps because of its unreadability? Or is it simply an author mocking art because he is frustrated at his inability to make a genuine contribution to it?

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.