Obscure Author Quarterly – Fent Noland, author of the Pete Whetstone letters

- Published: January 15, 2016

The following concerns the life of Charles Fenton “Fent” Mercer Noland, an Arkansas humor writer born in 1810, whose works are largely forgotten. I came across him by chance when I was looking into Arkansas’ literary history as part of a larger project I’m working on. I was immediately drawn to the fact that he killed someone in a duel and went on to become a politician, swampland commissioner, and fairly popular writer at the time. Noland authored the Pete Whetstone letters, humorous letters about frontier life written from the point of view of Whetstone, a fictional colonel.

Noland’s story, including his tenure in some fairly unexciting jobs, is full of adventure of the kind that simply doesn’t exist today. He lived in world where territories shifted, trading posts were frequented by all kinds of intense characters, and delivery of a state’s constitution entailed riding on horseback from Arkansas to DC, which Noland did, though he found that another copy had already arrived by mail well before he did.

Anyway, here is a little bit about this interesting character. I’ve written a more extensive biography as part of the aforementioned project, so please get in touch if you are interested or if you happen to know more about Noland’s life!

On February 5th, 1831, two men stood ready to resolve a dispute the only way they reasonably could – a duel. The honor of William Fontaine Pope, the nephew of Arkansas’s territorial governor, had been greatly aggrieved in print by Charles Fenton Mercer Noland, author of a newspaper piece claiming Governor Pope had sullied his office by selling liquor on the side. It was a grave public insult, but the younger Pope was used to addressing such affronts. He had already been in one duel that year, dueling with a Dr. Cocke over the contents of a newspaper article. Three shots were exchanged in the Cocke-Pope affair but none caused any injury, and the matter was considered closed since they had at least tried to shoot it out.

A portrait indistinguishable from that of every other man from his time period

And so perhaps emboldened by his semi-success in the first duel (ie he didn’t die), Pope found himself in another duel, this time defending the honor of his ‘one-armed and aged uncle,’ the alleged liquor-slinging Governor. Pope published a reply to Noland saying that anyone writing such egregious lies was looking for a fight, and that he, Pope, was ready to give it to him. Noland owned up to writing the article and a duel was arranged. This time Pope wasn’t so lucky. Noland’s first shot blasted him in the hip, and Pope succumbed to the injury a few months later.

Such was the life of a young man in a young Arkansas. Charles Fenton “Fent” Mercer Noland was twenty-one years old at the time, and had arrived in Arkansas by way of Virginia a few years earlier. He had been dismissed from West Point in 1826 for ‘deficiency in mathematics and drawing’ and was trying to figure out what to do with his life. His father had taken a job in Arkansas and Noland went to join him. It was an auspicious move – Noland was an adventurous sort and the Arkansas Territory was just the place for a plucky young man to see what he could get into. There was ample horse racing, one of his favorite pursuits, and he soon began palling around with old time settlers, hunting and learning the skills of a real woodsman. Noland’s accumulated experiences amounted to a fantastic cache of stories, and in 1836 he began writing letters to a New York newspaper about the huntin’ n’ fishin’ frontiersmanship of the Arkansas territory, told from the point of view of a fictional colonel named Pete Whetstone.

The Whetstone character was a sort of good-natured cad, brawling and racing and boasting his way across a heavily enrivered area in north-central Arkansas called Devil’s Fork. The rollicking letters solidified the idea that the typical Arkansan was a “sort of professional hunter who fought for fun and drank by instinct.” Pete – not ‘Peter,’ as he points out – is a salt of the earth guy resembling Noland’s deepwoods friends and a side of himself that Noland was very proud of. The letters were a regular, popular feature in a fairly respectable national sporting newspaper called The Spirit of the Times.

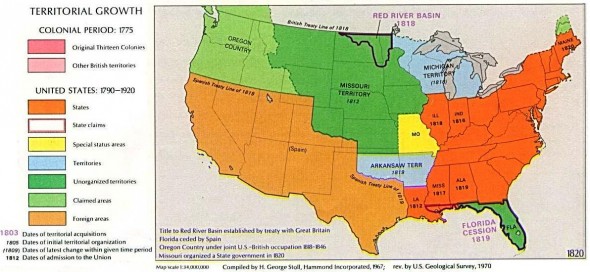

Note the Arkansas Territory, Noland’s stomping grounds

Over the course of the letters, there are bear hunts, marriages, a guy getting bitten by a goose, and Whetstone’s experience trying “sham pain.” Col. Pete Whetstone and his cohorts caroused and gambled and traveled across Devil’s Fork, where they often butted heads with their rivals from Raccoon Fork. Practically every other letter features some account of drinkin’ and fightin,’ which was usually the outcome of a horse race gone wrong, or very well. A few of these fights even turn into knife fights but the characters take their injuries in stride, as if getting one’s nose slashed was a pretty common occurrence. Letters advise readers against getting too bent out of shape about his exploits, advising that “if you don’t like the smell of fresh bread, you had best quit the bakery.” Such was the timbre of the time. It seemed that if Noland was exaggerating through Whetstone, it wasn’t by much.

The letters are full of raucous humor, but they are also an important document of life in the Arkansas Territory. The letters showcase games, dances, popular songs, courtship rituals, horseracing culture, political concerns, and food typical of the time. At one point Whetstone gives a political speech at a “logrolling,” a large gathering based around stacking the logs and branches left after building a house. Whetstone gets elected to the state legislature and the letters follow his career there, lampooning real politicians and issues. The satire was especially mordant, as the letters were written when Noland was a legislator himself. There are numerous jokes about a real politician named Tom Benton and his “stiff cravat,” though whatever this meant was so topical that nobody has been able to figure out the humor behind the insult.

Noland’s winning personality and hardy demeanor also served him well in his interest in regional politics, a pursuit apparently as equally bumptious as life out in the wilderness. Noland was elected to the state senate in 1836, where the House Speaker killed a representative in a knife fight during a session of the Arkansas General Assembly. Noland served as a pallbearer at the Representative’s funeral.

Noland wrote forty-five Whetstone letters over the course of nineteen years, and sports articles and editorials for even longer. Whetstone’s last letter, published October 10th, 1856, is an account of he and frenemy Dan Looney’s ‘big fight.’ Readers could take comfort in knowing that life would as normal on the Devil’s Fork, as the letter didn’t end with an emotional farewell but, of course, a brawl.

A modern collection of Noland’s letters. Noland’s editor died shortly after he did, which meant no compilation of his letters existed until more than 100 years after Noland died

In the larger context, because of his fictional Whetstone letters, Noland plays an unheralded role in the development of a larger American literary voice. He was part of a brief cadre of writers that existed in the first half of the 1800s, many of who wrote similar pieces for newspapers, in which a goofy lout recalls the larger-than-life events he’s witnessed. Their stories were very contextual, drawing humor from events of a time marked by tremendous change. He and his contemporaries comprise what is sometimes referred to as the “Big Bear School of Humor” and they captured the early 1800s zeitgeist to such a degree that their efforts have been dubbed an “Unofficial American Literature.” The characteristics of Pete Whetstone’s letters, the dialect, the keen eye, the nuanced characterizations, and the consistent quality of the writing, are qualities that have named Noland and his contemporaries precursors to Mark Twain and William Faulkner.

Whetstone’s entertaining missives granted Noland a minor national celebrity, but despite the popularity of Col. Whetstone – a British sports paper claimed Noland was the only American they would publish – Noland died in relative penury and the Pete Whetstone character faded into obscurity with him, existing only as a footnote in the casebook of American letters. A complete collection of the Whetstone letters was published in 1979 but not again until 2006, when the collection was reprinted with a new forward. Academic articles concerning Noland will appear once in a while in history quarterlies or as part of larger regional overviews, but the most modern editor of his letters, probably the country’s foremost Noland resource, was tragically killed in a car accident the early 1980s.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.