Luisa Owens’ poems bear witness, honor dead

- Published: June 4, 2015

Many of the original poems Luisa Owen will soon read in public spring from her childhood. But they’re not poems of innocence. Rather, they’re poems that describe a teenage girl gone mad after being raped; of an old woman’s body left on the ground for days before being removed; of a young girl whose mother has vanished. They’re poems that describe the terror and inhumanity of daily life in the concentration camp in Yugoslavia where Owen lived with her family shortly before the end of World War II, from the ages of 9 to 13.

While the poems address some of the worst things that humans can do to each other, Owen doesn’t seek retribution. Rather, she wants to bear witness.

“It’s a book of songs about the need to see our humanity,” she said in a recent interview. “Whatever is human needs our understanding.”

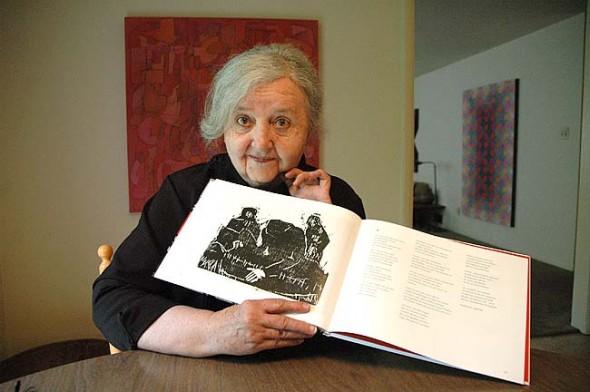

Owen will read from her book, Des Bischof’s Kleid (The Bishop’s Cloak), on Friday, June 5, at 7 p.m. at the Epic Bookstore downtown. The book, which was published by the Serbian publisher Banater Kuttur-Zentrum in 2013, features woodcuts from the illustrator Robert Hammerstiel.

Owen wrote the poems in German and she will read them as they were written. To her, writing in her native language is “reclaiming my language, my voice.”

And while it may seem the poems indicate a revisiting of her childhood, Owen says there is no such thing as revisiting, because the experience has embedded itself in her being.

“I’m not going back because this is always with me,” she said. “It’s part of who I am. I don’t know who I’d be without it.”

Owen recently recalled her early childhood in a bucolic village in Yugoslavia, where several ethnic groups lived peaceably with each other. But that all ended during the fall of 1944, described by historians as the “Bloody Autumn,” when the Yugoslavian dictator Josip Tito and other Communist leaders rounded up ethnic Germans who lived in the country. Some were assassinated, others forced into camps.

Owen remembers that autumn as “rainy, rainy, rainy,” and the villagers who chose to flee traveled muddy roads with their belongings in overfull wagons. Her family stayed, until late one night they were rounded up by strangers, who told the family they had to leave their home in five minutes. Owen and her mother and grandparents were taken to another village where 20,000 were forced into space where 3,000 once lived, with 40 people living with Owen in a three-room house. The village was surrounded by barbed wire, food was scarce and the ethnic Germans were treated as animals, according to Owen.

“We were starving,” she said.

Her family survived, and not long after their internment, came to Cincinnati to live with relatives. When she grew up, Owen, an artist, married, raised a family, and taught at Wright State University. She has lived in her Corry Street home for more than 40 years.

While Owen led a mainstream American life as an adult, she couldn’t look away from her history. When the Bosnian/Serbian conflict of the early 1990s erupted, the images of suffering people in her homeland sparked powerful memories. She wrote those memories down in her first book, “Casualties of War,” a memoir.

Owen wrote that book in English. She and the book’s publisher, Texas A&M University, expected that someone would translate the book into German, but no one did. So when she began writing her recent book, Owen felt compelled to delve herself into the language of her childhood.

This book was sparked by a 2006 trip back to her homeland, to the village where she and her family were incarcerated. Owen was invited by the trip’s sponsors, a reconciliation organization, to give a reading of “Casualties of War” to her 120 fellow travelers, who traveled from Austria down the Danube River to Budapest and from there to the former concentration camp site. While Owen had previously visited the village, this trip included a visit to the site’s mass grave, where an estimated 10,000 Germans had been buried.

The visit to the grave site prompted powerful feelings, Owen said. Only one other traveler out of the 120 had actually lived in the camp, so Owen felt surprisingly lonely, with almost no one to share her memories. And she expected to feel hatred for the Serbian officials who accompanied the group as a way to seek retribution for all those who died, she said. While initially Owen did feel intense anger, she was soon surprised by the complexity of the experience.

“Then I remembered that these men were children back in 1992, and I felt overwhelmed by love,” she said. “I was ready to hate them but I couldn’t. It didn’t matter that they were the enemy. I’m not religious but it felt like a piece of grace.”

Owen’s new book examines her experience during the 2006 trip back to the concentration camp site, and also revisits her own memories of living there, along with earlier childhood memories. And while the subject matter is similar to that of “Casualities of War,” the end result is quite different, Owen believes, because this time she chose poetry to express herself, and because she writes in her native language.

Poetry felt right as a way of going deeply into the experience, Owen said, but she had little experience writing poems. Still, she delved into the project, and ended up feeling amazed at the process.

“I didn’t write the poems,” she said, “The poems wrote themselves.”

Owen feels satisfied with the end product, brought to life by the haunting woodcuts of Robert Hammerstiel. The book feels like a love song to her childhood home and to her native language, she said. And she hopes that it helps in some way to remind others of her people’s suffering, to give voice to the dead, so they will not be forgotten.

One Response to “Luisa Owens’ poems bear witness, honor dead”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

I greatly appreciate Luisa Owens’ courage in activating the painful memories of her years from age 9-13 in her book “Casualties of War,” and now her poems. Her book was very moving and well-written. If my German was adequate, I’d be sure to attend her reading this evening. Writing and other artistic expression has a healing impact as one struggles to come to terms with trauma. She does not give in to the temptation to withdraw and avoid triggering these traumatic experiences. Her writing converts them to memories so that she is less likely to endlessly re-experience them. Thank you Louisa; and to you Diane for this article. Esther Battle