An Antioch alum’s journey to the bench

- Published: July 25, 2019

Growing up poor in New York City, the daughter of a teenage single mom, the Honorable LaShann DeArcy Hall didn’t expect to become a federal judge.

“If you looked at my bio as a child … no one could have thought I’d be here today,” she observed last Friday in a frank public talk at Antioch College. About 80 alumni and villagers attended, many visibly moved by her remarks.

The 1992 Antioch graduate described her journey to the federal bench as the second annual speaker for the Honorable A. Leon Higginbotham Jr. Distinguished Seminar Series Presentation. The series honors federal judge and civil rights activist Leon Higginbotham Jr., a 1949 Antioch graduate who broke barriers for African Americans in public service and the law.

“We stand on the shoulders of giants,” DeArcy Hall said at the outset of her talk, referring to Higginbotham’s contributions.

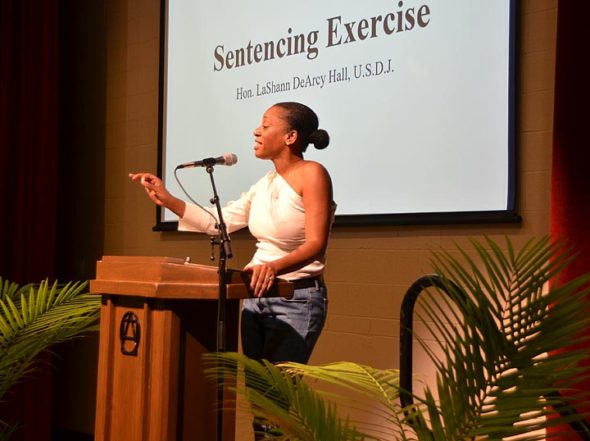

Her remarks blended personal history and reflections on the challenges of being a federal judge. She offered audience members a taste of one of those challenges in a “sentencing exercise” that highlighted all the factors judges weigh in setting sentences for those convicted of federal crimes. DeArcy Hall also spoke about the importance of her time at Antioch.

“Boy, am I glad I came,” she said, repeating the phrase with obvious emotion.

“Antioch was where I learned to have a voice,” she added, describing a pivotal moment after the Rodney King beating in 1991 in which she and others on campus turned a sense of powerlessness into the resolve to organize a protest march. Antioch students joined with those from Wilberforce and Central State University to march from the Antioch campus to downtown Xenia, she recalled.

“That day, I truly came into my own. It was profound for me,” she said.

DeArcy Hall also paid tribute to her mother, who had a partial high school education and faced steep challenges as the single parent of two daughters.

“My mother had to fight through circumstances that would have broken most people,” she observed.

Yet, because of her mother’s strength and support, DeArcy Hall grew up with the sense that “I could have and be anything that I wanted to be in this life,” she recalled.

When DeArcy Hall was 25, she changed her original surname of Jones to DeArcy, her mother’s last name, to honor the woman who raised her. Hall is her married name.

If Antioch gave DeArcy Hall a voice, it didn’t necessarily give her a direction, she reflected, laughing heartily. After Antioch, she pursued a career in dance, taught English in South Korea and served for three years in the U.S. Air Force. Her time in the military broadened her perspective, according to DeArcy Hall.

“I wasn’t as open to seeing all perspectives when I joined the military,” she admitted. “I was misguided about the individuals in the military,” she added, making a distinction between the nation’s military policy and the diverse individuals who actually serve.

She ultimately found her way to the law, a field she hoped would satisfy her intellectual curiosity and allow her to “do some good.” DeArcy Hall entered Howard University Law School, a historically black institution, graduating with honors in 2000. For the next 15 years, she worked in commercial litigation, often defending Fortune 500 firms. Her career in “big law” was not as “inconsistent” with civil rights goals as it might have seemed to some of her fellow Antioch alumni, she said.

As one of the very few African American women in commercial litigation, she was often alone in a room of “gray-haired old white men who didn’t expect me to be there,” she recalled.

“That’s breaking a barrier,” she said.

She joined the law firm of Morrison & Foerster LLP in 2010, and was made partner in 2014. Then in late 2014, she was nominated by President Barack Obama for a federal judgeship. She was confirmed by the U.S. Senate to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York in late 2015. As a federal judge, she handles criminal and civil cases under federal jurisdiction, including those that involve the U.S. government, the U.S. Constitution and federal law.

There are currently 677 U.S. District Court judgeships in the country, according to Ballotpedia. The U.S. District Court system is two layers beneath the U.S. Supreme Court in the federal judiciary.

African Americans hold just 85 of all federal judgeships, DeArcy Hall noted in her remarks.

“That’s not a lot,” she said.

As a black woman, she makes a point to bring all aspects of her identity to the bench each day.

“I cannot shed any part of who I am,” she said. “I must get on the bench as a black woman who grew up poor in New York City.”

She invoked a traditional African-American ideal instilled in her at Howard University: “We must lift as we climb.”

“If I don’t help the next young person, it doesn’t matter that I’m here,” she said of her presence on the federal bench.

DeArcy Hall said she finds the work of a federal judge rewarding and challenging. In civil cases, one of her most important roles is giving defendants, particularly those not represented by lawyers, “the opportunity to be heard.”

Regardless of the case’s resolution, “it makes a difference in their lives that someone in my position just listens to them,” she said.

Criminal cases present another level of challenge.

“My work there is tough,” she said. “The fact that I am who I am informs how I deal with people who come before me.”

She spoke in detail about her relationship with one defendant under federal supervision. She worked with him closely to get him to the date after which he would be released from oversight. On that day “he came into my courtroom and we embraced,” she recalled.

The hardest part of her job is sentencing, DeArcy Hall reflected. Federal judges have tremendous discretion to set sentences for those convicted of federal crimes. While a few crimes have mandatory minimum sentences, in most cases, it is the judge who determines the type and length of a sentence. Judges refer to sentencing guidelines, but are not bound to follow them, she explained.

“The authority is not something you enjoy,” she observed.

After handing down her first couple of sentences, DeArcy Hall retreated to her chambers and played Gospel music to recover from the experience.

“I needed Jesus in my chambers,” she recalled with a laugh.

She still keeps her schedule clear following sentencing in order to process the experience and deal with the emotional toll.

“It doesn’t matter if the crime is awful, atrocious,” she said. “Behind [the defendant] in the gallery is their mother, brother, sister, spouse. And too often their child.”

To dramatize the challenges and intricacies of sentencing, DeArcy presented a partially fictionalized scenario involving armed robbery by a former convicted felon, then elicited feedback from audience members on how to appropriately set the sentence for the crime. The exercise spurred discussion of a range of factors a judge typically considers, including characteristics of the crime, the defendant’s prior criminal history, the defendant’s personal history and upbringing, the need for the sentence to reflect the crime’s seriousness, the need to protect the public, the need for the sentence to act as a deterrent to future crimes and the kinds of sentencing options available.

One audience member meted out a lighter sentence than the recommended range of 97 to 121 months for this particular crime, while another questioned the efficacy of any jail time.

DeArcy Hall noted that she has taken to heart the wisdom of a mentor in the judiciary: “If you start to get comfortable with sentencing, you shouldn’t be doing it.”

Separate from her talk, DeArcy Hall was awarded the 2019 Walter F. Anderson Award by the Antioch College Alumni Association. Nivia Butler, ’88, presented the honor, which recognizes those who have shown “fortitude and effectiveness in promoting diversity within the Antioch community and beyond.” Walter Anderson was a longtime music department chair at Antioch, and the first African American department head at a historically non-black college.

2 Responses to “An Antioch alum’s journey to the bench”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

Hi Courtney, Thanks for correcting that date. I’ve updated the article accordingly. –Audrey

CORRECTION

Actually, Judge DeArcy Hall made partner at Morrison Foerster in January 2014 and a few months later, was interviewed by Senator Gillibrand

to see whether she was seasoned enough to serve on the federal bench (of course she was).

After the White House interview, she was nominated in late 2014 by President Obama.