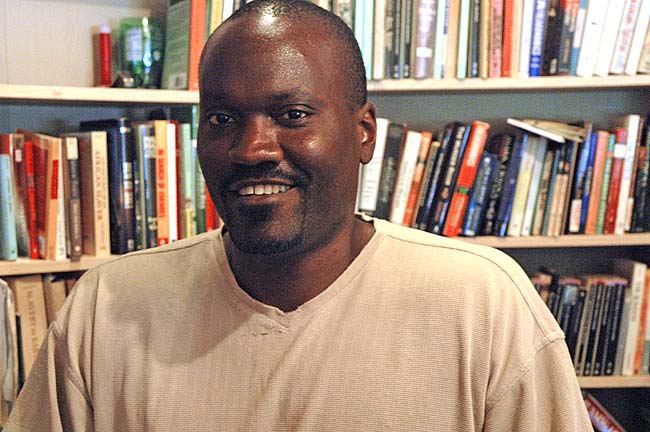

Wright State professor Opolot Okia— Reexaming slavery

- Published: October 4, 2012

In certain eras, it has perhaps been easier to say that slavery and forced labor are wrong than to live that principle. At least that’s how the British appear to have seen it as they went about colonizing East Africa in the 19th and early 20th centuries. According to newly published research by local resident Opolot Okia, the British did in fact continue a practice of forcing Kenyan citizens to work for both public and private endeavors well after slavery was outlawed. Okia’s book on the subject, Communal Labor in Colonial Kenya: The Legitimization of Coercion, 1912–1930, was published over the summer by Palgrave Macmillan. And his research on the subject is far from complete.

It has heretofore been accepted among scholars of colonial African history that forced labor ended when the practice was outlawed by the British in 1927 and then again by the International Labor Organization of the League of Nations in 1930. But if that were true, Okia reasons in his book, his encounter with stories such as the one he uses in the introduction would not have been commonplace. The story concerns a missionary named Walter Owen who in 1929 observed five women and an elderly man performing repair work on a major road near the town of Maseno in western Kenya. The workers had been assigned by their chief to perform the “community service,” which was neither voluntary nor negotiable, and Owen reported the incident to the district commissioner because it was illegal.

Okia came across enough stories like this on paper that he thought it worth gathering more in person to add evidence to their status as the prevailing practice at the time. So in 2007, as a Ph.D. student at West Virginia University, he received a Fulbright Fellowship to move with his wife Simeon Kresge-Okia and their son, Oluka, to the Nyanza area of southwestern Kenya to teach at Moi University and complete the research. There he found many elders of the popular Luo ethnic group who testified to the compulsory work they had been expected to perform for several hours or days each month for little or no pay in the name of community service — service that had indeed been an East African “tradition” but which was being exploited by the British occupants for their own gain, Okia argues. Many of those he interviewed said that if they refused to come to work, they were dragged from their homes and beaten.

Adding insult to injury, Okia points out in his narrative, the British justified their labor practices by fabricating the theory of the “lazy African” whose character was said to improve if forced to work more.

“Forced labor became a prescription for the ‘lazy African,’” Okia explained. “It tells you something about the way the colonial powers tried to define what were the acceptable terms for African development.”

Having spent a good part of his childhood in Uganda, another former British colony, with African-American ancestry on his mother’s side, Okia has a personal interest in how forced labor has shaped the history and culture of many parts of the world. His father grew up in colonial Uganda, which, like Kenya, had suffered nearly a century of forced labor practices before and after it gained independence in 1962. After Okia was born, his father brought his mother, who hailed from Louisiana, to Uganda, where the family lived until the early 1970s, when the country fell under the violent military government of President Idi Amin. The family then fled back to the United States and settled in Alabama, where Okia finished his secondary education amid the racial discrimination that has historically plagued the South. Seeing patterns and similarities between the two distinct African cultures, he became interested in exploring their shared history of using African labor for monetary gain.

While in Kenya, Oluka, now a Yellow Springs High School student, attended traditional Kenyan grade school. According to Simeon, Kenyans take education very seriously and offer rigorous academic programs even in schools with dirt floors and minimal infrastructure. But she was also troubled by the severity of the school’s disciplinary policies, which included corporal punishment for academic failure and other unacceptable behavior. While she liked living in Kenya, the cultural differences would have been difficult to adapt to permanently, she said.

So when the fellowship ended, Okia applied for a teaching position at Wright State University, where he is currently an assistant professor of history, specializing in African history.

While his most recent book focuses on Kenya up to 1930, Okia feels that more needs to be written about the pervasiveness of coercion as a tacitly accepted practice throughout colonial Africa well into the independence era of the 1960s and beyond. His next research project will take him back to his ancestral region in Uganda, where the oral tradition might unearth some previously untold stories about slavery and what led to a long-held practice of “bounded labor.”

2 Responses to “Wright State professor Opolot Okia— Reexaming slavery”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

Perhaps miracles do happen, but there were serious accidents from Maseno to Luanda due to the bad condition of the road over there.

I wonder if that road near Maseno is any smoother today.