New documentary by Aileen LeBlanc—Ethiopian Jews seek spiritual home

- Published: November 15, 2012

It was part Mission Impossible, part Exodus: a pair of covert plans veiled with code words from the Old Testament.

On Nov. 21, 1984, a squadron of Israeli airliners, dubbed Operation Moses, landed in famine stricken Sudan and evacuated 8,000 Ethiopian Jewish refugees to Israel. Seven years later, in a follow-up 36-hour mission — Operation Solomon — 34 Israeli cargo planes and airliners landed in Ethiopia and airlifted an additional 14,000 Ethiopian Jews to the Promised Land.

Those are the old headlines. But the story continues. And while thousands of Ethiopian Jews were finally settled in Israel, thousands more were left behind, caught up in bureaucratic limbo.

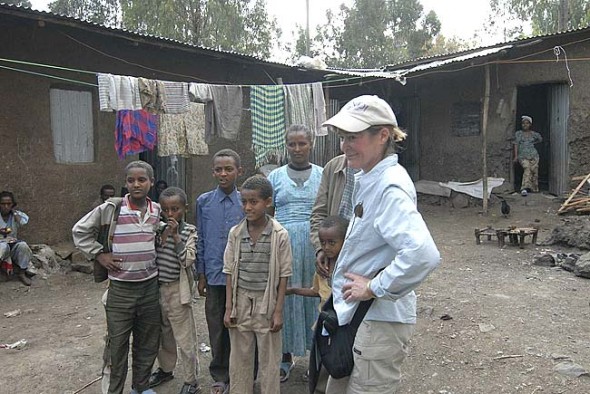

Yellow Springs filmmaker Aileen LeBlanc picks up the saga of those stranded Ethiopian Jews, the Falash Mura, in her recent documentary “Take Us Home.” The 70-minute film follows the lives of several of those families who abandoned their villages and relocated to a small Jewish community in Gondar, a picturesque city in northwest Ethiopia. For the Falash Mura, Gondar was supposed to be a staging ground, the first leg of a long held dream to finally reach Jerusalem. But the families have been isolated in Gondar, enduring years of political hurdles that have frustrated their efforts to stake their claim for a place in the Jewish homeland.

The film will premiere on Thursday, Nov. 15, at the Dayton Art Institute. The event sponsors are the DAI, WYSO, Jewish Cultural Arts and Books Festival and FilmDAYTON. The event will begin with a reception at 7 p.m. and include the screening and a Q&A with filmmakers and stars of the film. Tickets are $5 and can be reserved at daytonartinstitute.org.

LeBlanc’s approach to telling the story of the Falash Mura was in line with the way she’s consistently framed her work during her career in public radio and television.

“My approach to telling this story is for you to get to know these people on a very personal level so that you then care about what they’re having to deal with,” she said.

“If I bring up all the issues at first and I say things like ‘Ethiopian Jews’ to Americans who don’t know anything about them, they’re going to tune out because they can’t immediately relate to it. And that’s because a lot of Americans who are not Jewish don’t know about this issue. They see the Ethiopians as victims of the famine. And that’s what they relate to in their minds.”

LeBlanc was approached about the project in 2006 by Karen Levin of the Levin Family Foundation in Dayton. Levin had traveled to Ethiopia because her foundation was asked to fund Operation Promise, an organized effort to help Ethiopian Jews immigrate to Israel. After spending time in the country and learning about the plight of the Falash Mura, Levin asked LeBlanc to produce a documentary. The Levin Family Foundation has provided the major funding for the documentary.

The documentary got underway in February 2007, when LeBlanc began shooting in Ethiopia. In all, she and her crew made five trips to Ethiopia, staying various amounts of time—the first for three weeks. The trips usually involved jumps from Ethiopia to Israel. For the next two years, LeBlanc and crew, including co-director Orly Malessa, an Ethiopian Jew who has lived in Israel most of her life, followed the ordeal of several Falash Mura families.

“We really didn’t know how the story was going to end,” LeBlanc said. “We had no idea.”

LeBlanc’s initial trip to Ethiopia was a bit of a jolt.

“It was immediately shocking to see how people lived,” she said.

“I was almost afraid to say anything because I was overwhelmed with being so totally out of my comfort zone in every way possible.

“But it’s a beautiful country and the people are dear. They’re extremely polite, extremely gracious. You don’t walk by people on the street and look at your feet. You acknowledge them. You greet everyone.”

Although LeBlanc’s primary focus is on the day-to-day struggles of the Falash Mura, the documentary offers some interesting historical insights.

At one point, we meet Micha Feldman, an Israeli, who works with Ethiopian Jews who have settled in Israel. In an interview he says one of the biggest problems facing the Ethiopians who were rescued in Operation Moses was starvation and family disruption.

“There was no one family without losing someone, burying someone in those refugee camps,” he said. “They arrived like skeletons. And one of the big problems was that there was almost no family that came [to Israel] complete.”

LeBlanc also interviewed Asher Naim, the Israeli Ambassador to Ethiopia at the time of Operation Solomon. Naim says that prior to the evacuation the Ethiopian government, immersed in a protracted civil war, demanded Israel provide them with guns in exchange for the Jews. But the Israeli government refused.

“Then they said give us $100 million, otherwise we will not give [them] to you,” Naim says. “And we had to negotiate and we ended up with $35 million.”

LeBlanc’s film also highlights one of the biggest obstacles confronting many Falash Mura languishing in Gondar: Although most of them can trace their Jewish ancestry back for hundreds of years, many of their recent 19th and 20th century ancestors converted to Christianity, thus making them ineligible under Jewish law to emigrate to Israel.

LeBlanc was born in Detroit, grew up in Winchester, Ky., and earned a bachelor’s degree in theater design and technology from the University of Illinois. After graduating, she taught technical theater and lighting and eventually landed a job with the University of North Carolina’s theater department in Wilmington.

While working there, she was offered a position at a local TV station, where she learned the fundamentals of video and audio recording. In Wilmington, LeBlanc ended up managing a couple of local TV stations—an ABC affiliate and then a CBS affiliate—and then made the jump into public radio. At the public radio station in Wilmington she took over a half hour slot called “Sounds Local.”

“All of a sudden I had half-hour features to fill every week,” she said. “I did that show for seven years and then brought it to Yellow Springs. LeBlanc became news director at WYSO in 1999, where she worked for three years.

LeBlanc said that the Jewish community has been the biggest supporter of the project.

“They see the film as a Jewish film, whereas I see the film as a much broader story,” she said. “I see this as a story about, very simply, who gets to belong to what group, and who decides those things and why — which to me is extremely universal, and it’s something that happens in neighborhoods, in churches, in communities.

“You know we have people who are stuck [in Gondar]. They’re waiting because of nothing that they did, nothing about them. When they were back in their villages they had a better life. They had land. They had access to water. They could grow things. They could build their houses.

“But as soon as they moved to Gondar for the possibility of going to Israel, they lost their ability to work, and to a huge degree their dignity because their kids are sitting around doing nothing. A lot of the parents can’t get work so they’re relying on their families in Israel to send them money and that’s great for a month or two. But not for 10 years. But even with all that, they’re still hopeful.”

When asked if the efforts to bring thousands of Falash Mura to Israel has been a successful venture, LeBlanc equivocates.

“What’s the motivation for bringing the Jews there? If it’s the very basic one — to strengthen the Jewish state, to follow the mission of bringing all our brethren home — then it certainly has been successful from the point of view of the Israelis. And it certainly has been very expensive. It’s a lot easier to absorb — and that’s their term — a Russian Jew or wealthy American. But has it been good for the Ethiopians? From the point of view of the Ethiopians, I think they’re all happier in Israel than if they weren’t there. There have been very, very few who have gone back.

“But that is not to say that they haven’t lost a lot by leaving their culture and their way of life. But we’re talking basic human existence here. So when it comes down to whether or not I have running water and food and something over my head I’m going to pick that. Even if it’s not perfect.”

One of the most poignant moments in the film comes at the end. Worku Abe, a young Falash Mura recently settled in Israel, flies to New York with his student choir group to perform and tour the city. After seeing all the sights, from Times Square to Ellis Island, Abe reads a poem he wrote, “A Dream Comes True,” that celebrates the legacy of the Falash Mura:

Thousands of years ago I dreamt to go to Jerusalem.

I didn’t lose hope. The difficulties passed.

We will not lose hope till we prevail.

My dream came true.

After my trials, I thank God that I saw Jerusalem.

There were those who also dreamt.

And didn’t realize their dream.

They tried by foot and didn’t make it.

They died on the way or they disappeared.

My Jerusalem, this is for you.

To see you and to reside in you.

I dreamt a dream and it materialized.

In my heart I painted Jerusalem.

And now I still dream.

Till everything comes true.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.