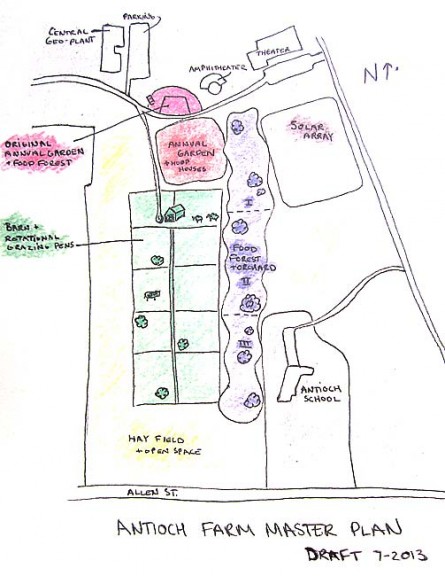

A conceptual rendering of the Antioch College farm by farm manager Kat Christen illustrates the multi-use plans the college envisions for the property long known as the golf course. Representatives from the college will present a revised land-use plan to Village Council on Monday, Aug. 5, with hopes of getting the zoning code to permit a certain number of farm animals on the property, to be used mostly for academic experimentation in sustainable agriculture. (Map courtesy of Antioch College)

Antioch College Farm raises animals, concerns

- Published: August 8, 2013

The six newly shorn lambs on the Antioch College farm huddled in the shade of their homemade hoop barn last week inside an electrified mobile fencing unit. About 20 yards away their feathered neighbors, 35 chickens and 15 ducks, clucked away in their own mobile yard, not far from the vegetable garden, a newly planted fruit orchard and a series of large compost bins. The activity on what is affectionately known as the Antioch golf course is just beginning, and it’s the heart of what Antioch College envisions for its sustainability program, one of the key components of the college curriculum.

Sustainability is a new program for Antioch and for the village as well, and it’s bringing with it marked change for what the community has for the past 90 years known as the Antioch College golf course — 30 acres of open field used by residents and Antioch School students for playing fields, pet walking and other recreational activity.

While the golf course is owned by the college and zoned educational, the college proposed at a Village Council meeting in July that farming with animals become a permitted use in that zone. What that zone will include in the future is yet to be determined, but the college is currently proposing the option of puting up to 1,400 pounds of animals per acre on the property (including poultry, sheep, pigs and possibly cows), for the purpose of educational practice and experimentation in food and land use sustainability.

The Village is still in the process of updating the zoning code and will consider the proposal at Village Council’s next meeting, Monday, Aug. 5, at 7 p.m., in Council chambers at the Bryan Center. Antioch Farm Manager Kat Christen and Glen Helen Ecology Institute Director Nick Boutis will be present to describe and answer questions about the college’s plans.

While the Village’s zoning update has driven the college to define what it envisions for the golf course earlier than expected, according to Antioch Chief Operations Officer Tom Brookey, the process has given the college an opportunity to broaden the dialogue with the community about the overall campus master plan. The college plans to hold a series of community meetings from August through November, incorporating drawings by Pittsburgh architects MacLachlan, Cornelius & Filoni, to communicate the plans with residents. And in August the college also plans to open a master planning board display in South Hall, where the public can stop by and study a map of the campus it envisions.

“We’re anxious to get our first thoughts out to see what everybody thinks,” Brookey said this week. “It’s a work in progress, but we want to just put out there ‘here’s what we’re planning; here’s the thought.’”

The farm

The Antioch farm was created chiefly as an educational learning lab for the college’s students, especially those interested in the sustainability curriculum. Christen, who started Smaller Footprint Farm, a community supported agriculture business, with her husband Doug in 2008, was hired by the Glen Helen Ecology Institute in 2011 to build and manage the farm.

The initial project included tilling a fourth of an acre just south of the science building behind the amphitheater to grow vegetables, fruit trees, and some native plants. The purpose was two-fold, to serve students in an academic manner and to serve the college kitchens with fresh, local food that would enable the college to walk the sustainability talk.

“We’re interested in sustainable farming here,” Christen said, which includes “practices that preserve or enhance water, soil and air quality…no synthetic fertilizers, only pesticides and herbicides approved by the USDA organic standards, and animal access to pasture most of the year.”

As the college has grown, so has the farm, which now has a half acre vegetable operation, a half acre food forest, including some fruit and maple tapping trees, medicinal herbs, and a large composting station used to recycle the food waste from campus (and including some manure from the Riding Centre to amend the farm’s soil.) Last year, the college also began raising 50 chickens and ducks for food, slaughtering two batches and keeping the rest for eggs. And this year the college added to the property six lambs, which it will slaughter in the spring for food.

The animals are kept in electrified pens made of flexible nylon fencing and moved every few weeks to ensure they get adequate access to fresh grass and bugs and to prevent overgrazing or overmanuring any particular area of the field, Christen said. The rotation of the pens is key to allowing the animals to live off the land in a continuous way, providing nutrients for the soil in the form of manure and then moving the animals to a new spot and giving time for the soil to absorb the nutrients and the grass to grow back. Such sustainable practices naturally alleviate the risk of bad odors and air and water pollution, according to Christen, who has seen the effects on her own Smaller Footprint Farm on Fulton Road in Miami Township, where she has raised goats and pigs.

The density of the animal population will vary as the college grows and continues to define its needs, but the more flexible the zoning is, the more easily the college can maneuver, Christen said. Though she couldn’t say how many animals the farm eventually hopes to host, because the operation aims to be diverse, there will never be as many of any one kind of animal as the density limits suggest, Christen said. In technical terms, Christen is proposing that the upper limits for animals be up to 1,400 pounds per acre, with additional per-acre limits of two pigs, or 1.4 cows, or 17 sheep, or 35 chickens. And given that only a third of the farm is slated for barns and grazing pens, the animals could be confined to less than 10 acres, with a minimum 100-foot buffer from any residential properties. (See the concept map).

The farm also serves a host of other needs on campus, according to Tom Brookey. According to the campus master plan, the golf course will also be home to the main geothermal wells that will heat and cool the Antioch gym, the science building and other buildings without the use of fossil fuels, as well as a solar array in the northeast quadrant to supplement the college’s power needs. The college plans to use the northern corner of the golf course for annual garden and hoop houses, the western quarter for animals, and a long narrow section from north to sound for food forest and orchard. The plan also includes keeping an open field just north of the Antioch School, as well as a hay field and open space along Allen Street.

The zoning

Earl “Pete” Hull recalls a time in the 1940s when villagers regularly kept chickens, horses, milking cows, and pigs in the village. Hull lived at the corner of High and Davis streets next to a Mr. Thompson, who raised chickens and a couple of pigs for annual slaughter. Garnet Williams had pigs too, which he took to Mr. Berley’s house on Walnut Street to be butchered. And Cassius Bell on Marshall Street had a work horse he used to haul barrels of waste for a living. According to Hull, though the homes were relatively close together, the smell of even the pigs was only really strong when it rained.

“When it rained it stunk up the neighborhood because it made the manure rot quicker,” he said. “But it didn’t last long.”

But residents did complain regularly, he said, and since the 1950s the Village has outlawed large farm animals within Village limits, except on land zoned for agricultural use, including the Glass farm and a few other open fields at the northern edge of the village, according to Village Manager Laura Curliss’s reading of the code. Now with the zoning code update, the Village is proposing to eliminate agricultural zones within Yellow Springs altogether, Curliss said.

The Antioch farm lies within the educational zone that encompasses the college campus. Under the current Village Zoning Code, animals are not a permitted or a conditional use in the education district. But in the current draft of the updated code, the Village proposes making farm animals a conditional use in education districts. However, because conditional uses require the property owner to reapply with a public hearing before Council for each land use change as it arises, the college had hoped to simplify the process by having its land uses, once and future, be defined and permitted. The proposal Council will consider this Monday is one that makes “farming with animals” a permitted use with the aforementioned maximum animal densities.

Animals under a weight limit of 200 pounds are currently allowed within the village. That regulation has allowed many homeowners around town to acquire chickens. And as long as the poultry provision doesn’t violate the Village’s nuisance law or elicit complaints from neighbors, chickens and other small pets are allowed, according to Curliss’s interpretation of the code.

Brookey wants villagers to be aware that though the college would like to define the provisions for the farm, neighbors and villagers will always have the force of the nuisance ordinance behind them.

“We’re trying be good stewards, and we don’t want to offend anybody, so there will be many protections for the neighbors,” Brookey said. “We want to let everyone know where we’re heading and what our long-range plans are.”

The neighbors

To date, most people Christen has spoken to are interested and supportive of the farm, and many families have visited the chickens and the sheep with great enthusiasm, she said. But talk about expansion of the current operations has many villagers thinking about how the farm could affect them and the village as a whole in the future.

Randi Rothman, whose home abuts the northern end of the golf course, is very supportive of the college and excited about its efforts to grow. And so far, the roosters she hears in the morning and the few sheep she sees in the field have been fine. But the idea of adding more chickens, cows and especially pigs to what is essentially her back yard has her a bit concerned, she said this week. While the current level of noise is mild and even melodious at times, a larger group of animals could threaten to raise a cacophony unsuitable for the lifestyle she and her family signed up for when they purchased their home over a decade ago. And the smell that pigs can produce would not be welcome, she said.

“My initial impression is I don’t mind waking up to roosters, the sheep are very cute, and the garden is lovely,” she said. “I think pigs would be a problem.”

Other concerns she has are about what the animal excrement could do to the groundwater and the fly population, and who will be responsible for consistent, long-term care of the animals.

“Will there be milk cows? Because milk cows need to be milked!” Rothman said. “It’s a big responsibility to run a farm, and it seems like Antioch has so many needs to get back on its feet … I hope it wouldn’t turn into an extra burden for the college.”

Another golf course neighbor, who wished not to be named, agreed that the current level of vegetable gardening and a few small animals is rather charming, especially as part of the college’s resurgence. But it is a change she hadn’t expected when her family purchased their home not too long ago, and she feels a little uneasy with the current level of unknowns about the farm.

Acknowledging that the golf course property belongs to the college, she still hopes that the neighbors can have some input, and that the community won’t have to give up the entire open field for the farm.

“We have no idea what they’re going to do. We saw that they’re allowing cows and pigs — that’s a bit difference from chickens and goats,” she said. “We didn’t anticipate living next to a large working farm … I would like to feel that the community and the neighbors at least had a say, even though it’s not our property, but we all have to live together and work together.”

Several other neighbors said they didn’t know much at all about the farm, its purpose or Antioch’s intention for the future of the property. And they would feel more comfortable, they said, if there was at least an invitation to talk about it.

“It should be a conversation with the Antioch School, YS Kids Playhouse, the neighbors, and the community,” Rothman said. “The golf course has sort of belonged to the village and been a multi-use space for years, and the change will affect that use.”

What students have gained

The farm’s other significant neighbors are the Antioch students, who, according to Christen, love the farm.

“Students say, ‘it’s really cool, I harvest greens in the morning, put them in the sink to soak, and by lunch I was eating them,” she said.

According to first-year student Sam Cottle, who co-oped on the farm last term, the college also incorporates the academic program into the living laboratory by, for instance, focusing one of the interdisciplinary global seminars on food. Throughout the course, students study how different methods of food production impact the world economy, hunger, politics, energy and the environment, then they go out and practice the sustainable kind of food production that’s good to the community, the earth and the human body. Students feel empowered by the opportunity to practice the values their sustainability program preaches, Cottle said.

“We can walk out and see what we’re talking about — the fact that we can bring in 40 pounds of beans in peak season with zero food miles and zero chemicals, that is very cool,” Cottle said. “It benefits the environment, it benefits the students, and it gives the chef something cool to work with.”

Cottle said that much of the proof of the health of the organic farm is in the food itself, which tastes and feels leagues better than the commercially-grown food he was used to eating back home in Perrysville.

“I’ve never eaten this healthy in my life,” he said.

Environmental science professor Linda Fuselier uses the farm as a lab for soil composition studies, the anthropology class experimented with an ancient variety of corn, and philosophy professor Lewis Trelawny-Cassity took students out to plant while discussing Decartes’ idea of plants having souls, Cottle said. And students themselves have used the farm to make and test biochar (a porous soil amendment made of pyrolized biomass), tap maple trees for syrup, and experiment with medicinal herbs, Christen said. And the students in professor Sara Black’s visual art and 2–D design course plan to design and build a barn on the farm.

“It’s an exciting experiential opportunity for students, which has been a long-time Antioch mission,” Christen said of the college’s tradition of mixing classroom academic theory with practical applications. “The main purpose of the farm is an educational learning lab.”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.