Classroom climate — How do YSHS students learn?

- Published: July 18, 2019

A YSHS/news collaboration

Editor’s Note: This is the final article in a collaboration with Yellow Springs High School. Written by students, the articles covered the critical issues YSHS students say they face. All the published articles are available at ysnews.com. Send any comments on the articles to jday@ysschools.org.

By Phillip Diamond

In education, presenting information is only half the battle. The classroom environment, both physical and social, and the way information is presented also has an impact on student learning.

As part of a project for John Day’s 11th grade psychology/sociology class, our group — Phillip Diamond, Olivia Snoddy, and Sayre Hudson — posed the question, “What is Yellow Springs High School’s approach to classroom climate?”

We gathered data via a schoolwide survey, which asked students how project-based learning, distraction and the physical environment impacted classroom climate. We also interviewed YSHS Principal Jack Hatert.

Hatert said he wanted students to enjoy their time in the classroom, regardless of whether they enjoy the content presented. This classroom enjoyment is largely dependent upon the dedication of teachers, he added.

“A kid doesn’t care how much you know until they know how much you care,” Hatert said. “It’s about establishing that trust, that support, that I, as an adult, care about you, as a kid,” he continued.

Research supports the idea that students’ perceptions of class are largely dependent on their teachers.

Hatert also stressed the need for teachers to engage students.

“If I just stand and speak, then [students] aren’t interacting with content at all,” Hatert said. “If they’re hearing about it, reading about it, talking about it and doing something with it, then the level of interaction is much higher.”

Interaction with content serves students on multiple levels. Instead of simply being presented with material, they confront it and must interpret it. Distractions are also minimized by pacing lessons quickly. Finally, content that resonates with students will be most effective in helping students learn.

“Relevance reduces restriction,” Hatert said. “If what kids are learning becomes relevant, then they’re going to be much less likely to push back against that learning and much more likely to just jump in and want to learn it.”

One teaching method designed to incorporate both engagement and relevant content is PBL, or project-based learning. YSHS has used PBL in its curriculum for the last seven years.

According to a male, ninth-grade YSHS student, PBL allows students to experience their learning, rather than simply memorize information. Another ninth-grade male stated that, in PBL, “I collaborate more with people, and I think more [than when in traditional school].”

Hatert referenced a middle school lesson where students compared protests in the 1700s with modern protests. Students in a traditional school may have been simply presented with information, but PBL students compared that information to a relevant topic, increasing their interest and engagement.

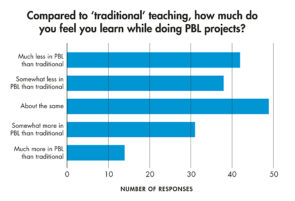

Despite the apparent benefits of PBL, an online survey of 177 9th–12th grade students — out of about 220 total students — conducted in April, reflected mixed student opinions.

Twenty-eight percent of respondents felt that PBL did not significantly improve their learning, reporting that they learned “about the same” compared to traditional schooling. Forty-six percent of respondents felt they learned somewhat less or much less than in traditional schooling, while 26% reported they learned “somewhat more” or “much more” in PBL compared to traditional.

A 10th-grade male student interviewed by group member Sayre Hudson described how he thought PBL classes were “too unstructured,” and not focused enough for quality learning to take place. However, an eighth-grade female student said that she prefers PBL because “we get to do a lot of different [activities] and it’s more interesting.”

Many of the interviewed students also mentioned that PBL experiences differ from class to class and project to project. The results suggest that PBL is only effective when done correctly, and may not resonate with all students.

Another important part of student-content engagement is limiting distractions. The survey also asked high schoolers about various facets about their daily lives, and revealed a high level of student distraction. About 90% of high school respondents were distracted at least once every period — about 80 minutes — with 57% reporting being distracted multiple times per period.

Students cannot learn effectively if they are distracted, even if content is being presented to them from multiple angles. To combat this, “The best classroom management tool is a well planned lesson,” Hatert said.

“Pacing is really important. If an activity is taking too long, kids’ attention for it diminishes, and then they become distracted,” he said.

Student responses to informal surveys conducted in the hallway echoed this.

“[I prefer] teachers that stay on topic the whole class,” said student Sulay Chappelle, implying more attention will be given to teachers with a distinct lesson plan. YSHS’s level of student distraction may decrease if teachers focus on interaction and pacing.

Another factor that impacts student distraction is the physical environment. However, according to the schoolwide survey, only around a third of high school respondents were often, sometimes, or continually distracted by the physical environment of their classroom.

Group member Olivia Snoddy focused specifically on physical classroom environment, and found that it also played a significant role in YSHS students’ preferred classes. Many stated that a classroom’s layout, or physical environment, was what made it their favorite. Snoddy also investigated which types of seating arrangements helped students learn, and found that they mainly preferred seats arranged in u-shapes or in clusters, and tended to not prefer seats in rows, potentially giving teachers valuable insight into how to engage students.

Varying views on project-based learning

By Sayre Hudson

The word among Yellow Springs High School students is that they don’t enjoy, and actually dislike, project-based learning. In a survey of students, one interesting finding is that perspectives on PBL vary by grade.

Overall, about 28% of the students who took the survey said there was little difference in their learning compared to the traditional style, about 26% of students said they learned more in PBL than traditional style, and about 46% of the students said they learned less in PBL than traditional.

YSHS freshmen have a more positive attitude towards PBL than older grades. When asked the question, “Do you think PBL has a better effect on your learning than traditional education?” freshmen tended to respond with helpful and kind feedback, which also showed a positive attitude toward PBL.

“Yeah, I think it does. It’s nice to experience what you’re learning. Some do it better the traditional way, but I prefer PBL,” one freshman responded.

YSHS sophomores seemed to have a more negative attitude when asked this question. One student gave the typical response: “I think it would if it were done right,” they said.

Juniors and seniors, meanwhile, seemed exasperated and annoyed when the subject was mentioned. They said that PBL is too unstructured and certain classes shouldn’t use it at all.

One curious finding that group interviews revealed was if the students were asked this question while they were among a group of friends, they all seemed to agree with whatever it was the first friend to answer would say. If the first friend said they liked PBL, the rest would agree. If the first friend said they didn’t like PBL, they would agree and follow up with the same reasoning as the first friend.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.