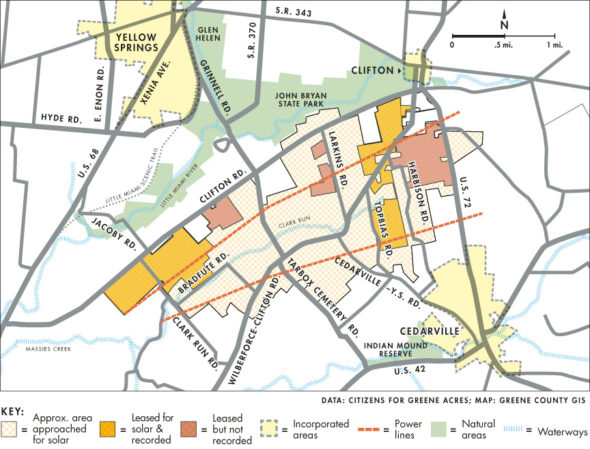

Australian company, Lendlease, has been approaching landowners in the rural area between Yellow Springs, Clifton and Cedarville for longterm leases to build a 175-megawatt utility-scale solar array. The darker-shaded areas represent properties where leases with Lendlease have been recorded with the county. Less shaded are properties that Citizens for Greene Acres has confirmed to be leased but that have not yet been recorded, and the larger area shows properties where solar leases were requested but either denied or not yet signed. The company says they selected the area in part due to its proximity to two power lines that run through it (pictured), while neighbors are, in part, concerned about the impact of the array on area waterways and recreational amenities (also pictured).

Township solar project divides neighbors

- Published: July 25, 2019

This is the first of two articles.

In the countryside southeast of Yellow Springs, an area of rolling farmland dotted with homes and barns may someday be the site of a massive solar array.

The Kingswood Solar Farm, if built, would span more than 1,200 acres in Miami Township, Xenia Township and Cedarville Township. And at an estimated 175 megawatts, it could be among the largest solar arrays east of the Mississippi River.

Some area landowners are now signing longterm leases with the Australian firm developing the array. They say the monthly payments of $1,000 per acre per year offered by the company, Lendlease, are too good to pass up. Farmland rents for between $200 and $250 per acre in the area.

Others are declining to sign up their land, and instead organizing in opposition to the project, citing concerns about the loss of prime farmland and rural character and potential negative impacts to wildlife, waterways and property values.

The quiet, rural area between Yellow Springs and Cedarville now finds itself at the center of a debate about solar energy and its tradeoffs, leaving the community, in the words of one resident, “torn apart.”

Lendlease has secured 43-year leases on almost 1,000 acres in the project area, according to organizers with Citizens for Greene Acres, the neighbor opposition group. It has yet to apply for a permit to build from the Ohio Power Siting Board, the state’s permitting authority for large-scale solar.

As the project gains steam, Citizens for Greene Acres is organizing a public meeting Friday, July 19, at 6:30 p.m. at Cedarville High School, 194 Walnut St., Cedarville. Speaking at the meeting are Dale Arnold, director of energy policy at the Ohio Farm Bureau; Matt Butler and Scott Elisar from the Ohio Power Siting Board, and Mike Schumacher, cofounder of the Little Miami Watershed Network.

This week, the News spoke with multiple neighbors and is presenting two representative viewpoints on the issue, along with a comment from Lendlease. A future article will cover the context and process for utility-scale solar, the pros and cons of large solar arrays and what residents can do to affect the outcome.

‘Not a good fit’

Lifelong farmer Joe Krajicek is one area resident who has raised his voice against the solar array. A small sign, “Say NO to solar farms,” stands at the end of his driveway on Tarbox-Cemetery Road, where the 62-year-old still farms and raises beef cattle.

“Its application here is not a good fit,” Krajicek said in a recent interview.

Krajicek farms a total of 1,100 acres in the area, 450 of which he owns. As more houses were built and the cement quarry in Fairborn expanded, he has seen the nature of the area change.

“We’re running out of greenspace in Greene County,” Krajicek said.

Krajicek declined to lease his land, and said he was disappointed with neighbors who chose to do so.

“It’s their property, but it has an impact on adjoining neighbors and the whole community,” Krajicek said. Some relationships have been strained by the situation, he added.

“The community is torn apart,” he said.

Krajicek was careful to say that he is not against renewable energy, but that he takes issue with the project’s placement on productive farmland, large size, corporate ownership and environmental impact.

To Krajicek, the soil in the area, with its high levels of organic material, should not be lost to solar. There are alternatives.

“Other solar areas are more isolated and thinly populated, with less productive farmland,” Krajicek said.

Although project details have not been released, Krajicek foresees environmental disaster with similar proposed projects.

Large fences, in the range of 8 to 10 feet tall, slated to surround the panels, will cut off wildlife from roaming freely, he said. Weed management under and around panels will likely require large, regular doses of chemical herbicides. And the use of gravel, the compacting of the soil and the change in the microclimate under the panels will have a long-lasting effect on soil productivity, Krajicek added.

“It will throw the whole ecosystem out of how it operates,” Krajicek said.

Despite remediation plans at other approved and pending solar sites in Ohio, Krajicek remains skeptical.

“What is the likelihood of getting the people responsible to put it back? It will never be as it was.”

In the end, Krajicek sees that his community will suffer the consequences while the benefits of green energy accrue to a large multinational corporation. He says that he would be in favor of community solar, by contrast.

“Any negative impacts stay here, but the benefits go out,” he said of the proposed large-scale project.

Solar, not development

Another lifelong farmer in the area made a different decision when he received a lease agreement in the mail two years ago.

Lamar Spracklen, who lives on Clifton Road, has farmed since 1958 and now farms about 3,000 acres in Greene, Clark and Madison counties. His family has lived in the area since the 1790s.

After learning that several neighbors had signed up their properties, Spracklen ultimately decided to lease a 65-acre parcel of land he owns on Larkins Road for the array. He said he did so because he didn’t want to miss out on an opportunity to support his farm and family with a payout several hundred percent more than what farming yields.

“The income will support the rest of the farming operation and my family and help my grandkids go to college,” Spracklen said of his rationale.

Historically low commodity prices were a factor in the decision, Spracklen added.

“Grain prices are barely enough to make a living on,” he said. “The big money in agriculture is made on buying and selling farms — it’s not grain.”

But Spracklen won’t sell his land for development, leaving him fewer options for keeping up with rising costs.

“I do not sell farmland for development. I think it should be preserved,” Spracklen said.

Compared with residential development, the fields used for the array will at least be able to be reclaimed as farmland at the end of the project, Spracklen said.

“If people want to build a house in the country, that’s their right. But most of those people built on good farmland, which will be gone forever unless you remove the cement,” he said. “Solar panels can be pulled out and farmland can be reclaimed.”

Spracklen said the project has created tension in the community and stress among some families, including his own. For instance, both Spracklen and his farmer son will lose some land they now farm to the array. His daughter-in-law has also spoken out against the project.

But in the end, Spracklen believes that the environmental effects and property value impacts of a solar array won’t be as significant as some neighbors fear. He doesn’t think that the area will “run out of farmland.” And because of the chemicals used in farming, many residential neighbors may end up preferring solar.

“Would you rather have a solar panel in your backyard or pesticides, herbicides, phosphate and nitrate?” he asked.

Company response

As the debate plays out in Greene County, Lendlease, which recorded $15 billion in revenues in 2016, continues to develop plans for the local array, its second solar project in process in the state.

Reached for comment this week, the company declined to specify exactly how many acres it is seeking in the area or to respond to neighbor concerns about possible negative environmental impacts.

But in a statement, Lendlease did respond to a question about why it selected the area for its project.

“We examine all options when it comes to siting solar arrays, and we selected the Cedarville area due to its favorable location for electric interconnection and positive response from landowners,” the statement read.

Lendlease also drew parallels to other solar arrays in the area, including smaller ones at Cedarville University, Antioch College and the Village of Yellow Springs, which are in the range of 1 to 2 megawatts, or about 100 times smaller.

“The project will be similar to other existing arrays that are currently in Yellow Springs and Cedarville, albeit at a larger scale, and will be electrically close to several coal plants that are in the process of being shut down.”

“We believe that installation of large-scale solar is a critical component of the transition to a renewable energy economy,” the statement concluded.

Lendlease’s other solar project is the Nestlewood Solar Farm, an 80MW array in Brown and Clermont counties in southern Ohio. That project is currently pending with the Ohio Power Siting Board, one of three pending utility-scale solar projects in the state. Six more large-scale solar arrays have been approved recently in Ohio.

One Response to “Township solar project divides neighbors”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

Let’s make this work. Conventional agriculture on the lands of interest includes many crops genetically modified to resist herbicides. Typical solar installations include low-growing, native grasses. These are available for grazing, such as sheep. There’s room for a mutually beneficial compromise here. The proposed project, although very large, is unlikely to negatively impact the historic farmland use.