COVID-19 contact tracing— More cases, more contacts

- Published: November 25, 2020

If you get an unfamiliar call, answer the phone.

That’s one message from villager Kirsten Bean, an employee at Greene County Public Health, or GCPH. Since June, Bean has been working as a contact tracer for the local health department, in addition to her main job as a health education program manager. She’s seen COVID-19 cases in the county escalate from one or two per day to dozens to well over 100. And with that escalation comes a proliferation of “contacts” — people potentially exposed to COVID-19 through a friend, family member or coworker.

“We have more people to contact every day,” she said in a recent interview.

The local health department’s contact tracing team now includes nine people, including employees from the Ohio Department of Health, part of the state’s scaled-up contact tracing workforce. The team works seven days a week, and during a recent week made about 750 calls, according to Bean.

Sometimes people answer, sometimes they don’t. Contact tracers try each contact three times. Because some contact tracers are not county employees, Bean cautioned that the incoming phone number may not have a 937 area code.

As she describes it, contact tracing is a race against time. Health department personnel want to reach people potentially exposed to COVID-19 to encourage testing and quarantining before they go on to spread the illness to other individuals in their home, school, workplace or community.

“It’s really about breaking the chain of transmission,” Bean said.

Right now, Greene County’s contact tracers are on schedule — they are calling every contact within 24 hours of getting a name. In Clark County, by contrast, the health commissioner recently stated that contact tracing had fallen behind under the pressure of escalating cases and a ballooning work load. With contact tracers running behind there, people who test positive for COVID-19 in Clark County are being asked to contact those they might have exposed to the virus.

This is something Greene County encourages, too, according to Bean. And in fact, about 95% of people she contacts are already aware that they might have been exposed to COVID-19. Contact tracers confirm this potential exposure — though they don’t reveal the identity of the infected person — and provide specific instructions for testing, monitoring symptoms and quarantining.

A worsening surge

But in another way, Greene County is beginning to fall behind. Contact tracers get their list of contacts from the county’s case investigators — the employees who reach out to county residents who have tested positive for COVID-19. And with cases soaring, the county is adding case investigations faster than employees can follow up.

“We’re starting to get behind on calling initial cases,” Bean said. Various health department employees — even “the IT guy” — are jumping in to help, she added.

According to GCPH epidemiologist Don Brannen, the county health department was conducting 1,333 case investigations as of Monday, Nov. 17 — a moving target. The county isn’t caught up on those, he wrote in an email, “because it is a work in progress and there is an increase in cases.”

A delay in contacting an individual who’s tested positive also means a delay in identifying who that person might have exposed to the virus. And that in turn means that contact tracers, however promptly they call identified contacts, are already lagging behind the spread of the virus.

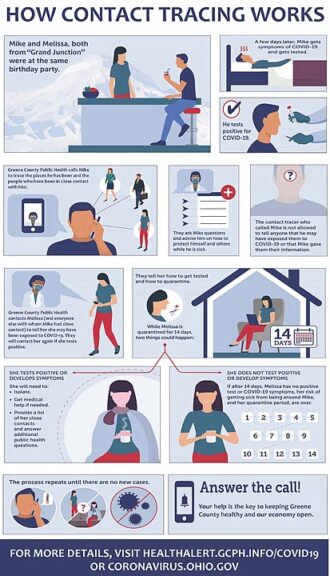

A graphic from Greene County Public Health provides an overview of how contact tracing works. Contact tracing is used by health departments to break the chain of transmission of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases by contacting people who may have been exposed to a confirmed infected person and encouraging them to quarantine for 14 days, monitor symptoms and get tested. (Graphic from Greene County Public Health)

Brannen emphasized the importance for anyone who tests positive for COVID-19 to self-isolate for 10 days. People with the virus — whether they have symptoms or not — should stay home and stay away from others, he said. And those who believe they’ve been exposed should quarantine for 14 days from the date of potential exposure.

Yet some in the county are not following those guidelines, he added.

“The impact of not isolating is apparent,” Brannen wrote. “We are seeing it in the surge of cases.”

That surge has worsened dramatically in November.

In the first 15 days of the month, Greene County added 1,322 new cases. That’s about 88 cases per day. By contrast, the county added 1,170 cases in the month of October, or about 38 cases per day. October was by far the worst month the county had seen — until November.

But timing and spread aren’t the only factors that can work against contact tracing, according to Bean.

Overall pandemic fatigue, misinformation and the reality that lots of people who are asked to quarantine for 14 days following a COVID-19 exposure won’t go on to develop the illness are factors that weaken the effectiveness of contact tracing — because they lower people’s willingness to comply with quarantines.

Bean said it was “hard to gauge” how many contacts asked to quarantine were actually doing so. While the public health department has authority under the Ohio Revised Code to enforce quarantines in some situations, GCPH is not taking a heavy-handed approach. Rather, the county uses a text-message-based system to prompt contacts to report symptoms each day. Nurses monitor reports of developing symptoms and reach out to individuals who may need to get tested for COVID-19.

But regardless of whether contacts get tested, they still need to maintain their quarantine to ensure they’re not passing the virus onto others, according to Bean.

“We really try to get people to comply. It’s in their best interest and the best interest of their community,” she said.

Yet in some instances, quarantining may be difficult or untenable, Bean acknowledged. For employed adults without paid sick leave, taking two weeks off may not be financially possible.

“Many people can’t afford to,” she said. “We’ve seen so many cases of people going to work symptomatic.” That’s a situation that contributes to community spread, especially where employers are lax about employee protections, she added.

Sources of transmission

Right now, about 70% of people being contacted by Greene County contact tracers are being exposed by an infected person in a K–12 school setting, according to Bean. Somewhat counterintuitively, however, that doesn’t mean schools are settings where lots of people are contracting the virus.

School case data bears that out, with fewer cases at area schools than many feared at the start of the school year. In Yellow Springs, which so far has opted for remote learning, one student is currently positive, and a total of 10 students and two staff are in quarantine. The case and most of the quarantines are not related to school exposure.

“Most of [school] contacts are not becoming positive,” Bean explained of contact tracing investigations conducted at schools.

Rather, she added, schools are one type of setting in which lots of people “interact in low-risk ways” — provided social distancing and masking are being practiced. An infected person in a school setting may trigger multiple contact tracing investigations and quarantines, with few or no contacts ultimately becoming positive.

“Where we’re seeing spread is not necessarily where we’re seeing the most contacts,” Bean said.

Transmission at extended family gatherings or within households seems to be a major driver of virus spread in Ohio, state and local officials have repeatedly said. About one-third of people who’ve gotten the virus in Greene County were infected by a household member, Greene County officials have stated in recent weeks.

It’s not always clear, however, where the person who introduced the virus into a household got exposed to the illness. Contact tracing is not about pinpointing the infected person’s prior exposure, but about preventing future exposure to other individuals.

“We don’t always know where we got it, but we do know how to prevent spread,” Bean said.

Ohio is beginning to gather more information about the source of an infection in a process known as backward, or reverse, contact tracing, according to a recent report on Cleveland.com. Such contact tracing goes back further than the customary two to three days to examine an infected person’s movements and contacts over the prior 14 days, the time of incubation for the virus. That is not the form of contact tracing practiced by Greene County, and may not be practical for overburdened local health departments.

Per CDC guidelines, contacts identified for the purpose of contact tracing reach back two days from the time an infected person developed symptoms or tested positive. And contacts — also called “close contacts” — are specifically defined under CDC guidelines as individuals who have been within six feet of an infected person for 15 minutes over a span of 24 hours. Those 15 minutes don’t have to be consecutive to constitute exposure, per a recent CDC guideline shift. Masking or its lack is not considered as part of the “close contact” criteria, the CDC states.

Yet it’s also true that masking and social distancing combined are highly effective at curbing transmission. That’s the refrain sounded by public health experts for months, and reinforced last week by Gov. Mike DeWine with a strengthened mask order that applies to Ohio businesses.

Brannen wrote in an email that such measures dramatically reduce people’s chance of contracting the virus in the event of COVID-19 exposure.

“If [people] are wearing a mask and social distancing, this will decrease the rate of transmission by up to 70%,” he said.

While effective, these simple, nonpharmaceutical measures “simply are not being adhered to by enough people consistently,” GCPH’s latest COVID-19 situation report from Nov. 13 states.

And that may be because the virus still seems abstract to some area residents, despite soaring county and state cases, Bean speculated. For members of the county’s contact tracing team, however, COVID-19 and its impact on families and communities “feels so real.”

“All of us have talked to people who’ve passed away [from the virus],” she said.

And though the workload piles up as cases scale up, Bean expressed gratitude for the chance to help a community through a crisis.

“It’s a large volume of work,” she said. “But it’s also really a privilege to do this work.”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.