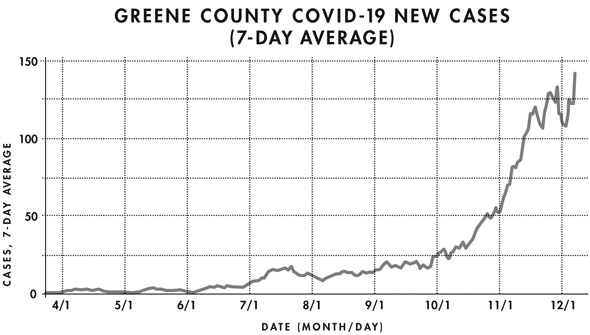

Greene County cases have continued to surge this month. The county added 955 cases in the first week of December, for a seven-day moving average of 142 new cases per day. On Tuesday, Dec. 8, Ohio posted 25,721 new cases, about 13,000 of which were a backlog of positive antigen cases dating back to Nov. 1. The county’s Tuesday case number of 255 was also affected by that backlog. (Chart Data from Ohio Department of Health)

Health Commissioner Melissa Howell— A closer look at area surge

- Published: December 22, 2020

Ohio saw a massive bump in COVID-19 cases on Tuesday, Dec. 8. That day, 25,721 new cases were reported, bringing the statewide case total well over the half-million mark since the pandemic’s start. About 13,000 of the new cases represented a backlog of positive antigen tests dating back to Nov. 1, according to state health officials.

But that still left about 12,721 new cases added in a single 24-hour period — by far Ohio’s largest day of cases.

Compounding the case data were record-breaking numbers of new hospitalizations and ICU admissions. Ohio added 657 new hospitalizations on Tuesday, including 67 patients admitted to the ICU. The hospitalization number was amplified by the antigen test backlog, which contributed about 100 additional hospital admissions to the total, state health officials said.

The backlog suggested that November — already the worst month of the pandemic — was even more dire than the state numbers had suggested. In addition, Tuesday’s case surge outside of the backlog was perhaps the first hint of the Thanksgiving fallout widely predicted by public health officials.

Greene County also saw a spike on Tuesday, with 255 new cases reported, the largest-ever number in a single 24-hour period. In the first week of December alone, the county added 995 cases, as well as 56 hospitalizations and 10 deaths.

Speaking with the News the day before, Greene County Health Commissioner Melissa Howell said the county had seen an uptick in family groups getting tested last weekend, 10 days after Thanksgiving. It was still too early to tell what the impact of Thanksgiving celebrations would be, she said on Monday.

“Our cases are still rolling in,” Howell said.

But the Tuesday case number seemed to provide a potent indication of what might be on the horizon.

Melissa Howell has led the county’s pandemic response as the Greene County Health Commissioner. (Submitted photo)

The News interviewed Howell and her Greene County Public Health colleague Don Brannen, the county’s epidemiologist, on Monday to hear more about the health department’s response to the pandemic that so far has sickened at least 7,024 people and cost 84 lives in the county. The interview covered county trends, hospital capacity, contact tracing, masking and health department actions in response to the virus.

County trends

As of Tuesday, Dec. 8, Greene County was adding new cases at a rate of 142 per day, based on a seven-day moving average. That average includes Tuesday’s case spike. The 21-day moving average was a somewhat lower 126 new cases per day.

The county added 3,086 cases in the month of November, or over 50% of cases added during the whole of the pandemic up to that point. With more cases added in the first week of December than in the first 12 days of November, Greene County seems to be experiencing an accelerating surge this month — even before the effects of Thanksgiving and the upcoming winter holidays are factored in.

Asked where outbreaks were occurring in the county, Brannen said that long-term care facilities, school settings and family gatherings remained contexts where county health officials were seeing clusters of cases. Howell emphasized that pinpointing the source of outbreaks was difficult, due to extensive community spread across the county.

Geographically, cases have been growing more rapidly in rural parts of the county in recent weeks, consistent with state trends, according to Brannen.

“We’ve seen a shift from more to less populated areas,” he said, referring not to absolute numbers but to per capita rates.

For example, the 45335 zip code, centered in Jamestown, has one of the county’s highest per capita case rates. The case rate is well over one-and-a-half times as high as the 45387 zip code, where Yellow Springs is located.

While Ohio is now reporting cases by zip code, there is currently no way for the local health department to track or report cases by the narrower category of municipality. So Greene County Public Health does not know how many cumulative cases there have been in Yellow Springs. In addition, the county health department is no longer updating a spreadsheet of local cases that previously alerted local first responders to the location of current (not cumulative) cases within their jurisdiction. That information is available from the state.

The News has previously estimated that the village has seen at least 40 cases. No updates to the Nov. 30 report of two active cases here were available as of press time.

Hospital capacity

While hospital capacity has emerged as a crisis issue for many parts of Ohio in recent weeks, Howell said area hospitals have so far been able to keep pace with COVID-19 cases.

In a Nov. 24 presentation to the Greene County Board of Commissioners, Howell stated that area hospitals were at two-thirds capacity, with an ability to further “flex” to accommodate more patients. For example, Soin Medical Center in Beavercreek had expanded its ICU capacity from 14 to 30 beds, she said.

Soin is one of two hospitals in the county; the other is Greene Memorial Hospital. Both are part of the Kettering Health Network. Early last year, Greene Memorial announced the closure of its ICU after a doctor group pulled out in February, leaving just the Soin ICU to serve the county.

With hospital leaders around the state warning the public about staffing shortages and the need to postpone nonessential surgeries, Howell said area hospitals are not in that position.

“They continue to say that they are OK in our area,” she said.

And care for COVID-19 patients has gotten more effective and efficient overall, Brannen pointed out. New treatments have improved outcomes, and patients are being safely discharged earlier once they’ve “made it over the hump,” he said.

Precise hospital capacity numbers are hard to pinpoint. Eye on Ohio, an investigative journalism nonprofit, has obtained hospital capacity figures for hospitals around the state through a public records lawsuit. That group’s numbers show that Soin Medial Center had five ICU beds available as of Dec. 4, out of 25 total indicated. That same day, the hospital had just three regular hospital beds available, according to Eye on Ohio. Both figures suggest narrowing capacity as compared to the estimates provided by Howell to the county commissioners two weeks ago.

A News request to a Kettering Health Network spokesperson for current hospital capacity figures and related data for our area was not answered by press time.

While not in crisis now, the area hospital situation could deteriorate rapidly, Howell cautioned.

In recent weeks, hospitals have been busier than they have been at any other point in the pandemic, she said. In the past two weeks, state data shows that Greene County added 87 new hospitalizations. By contrast, the county added 67 in the prior two weeks, and 62 during the month of October.

“Perhaps the worst is yet to come. Things could get serious very quickly,” Howell said.

Contact tracing

In another part of its pandemic response, the county has seen swift changes.

As cases surged here in November, local public health workers struggled to keep up with contact tracing and case investigations, two related tools for controlling the virus’ spread. By late November, the county was at least 800 contacts behind, meaning that 800 county residents who were potentially exposed to a confirmed case of the virus had not been contacted, and advised to quarantine, in a timely way.

Prior to the pandemic, Greene County had two communicable disease contact tracers. That work force has recently been augmented by the county’s volunteer Medical Reserve Corps and contact tracers from the Ohio Department of Health. And nearly all of the local health department’s staff of 67 has played some role in contact tracing, with some employees having pivoted to contact tracing close to full time, according to Howell.

“Literally almost everybody has played a role,” she said.

To handle the recent case surge, the health department used Hyper-Reach, Greene County’s emergency notification system, to call contacts, and an online survey to collect information to augment case investigations. Thanks to those and other factors, the county is now caught up, according to Howell.

Until recently, contacts have been asked to quarantine for 14 days and check in daily with the health department during that period. A recent guideline change from the CDC has reduced the quarantine period to 10 days from the time of exposure for those who do not have symptoms and do not get a test, as well as seven days for those who do not have symptoms and get a negative test result.

Howell said she feels hopeful that the change will increase compliance and get people back to work or school faster, but she is also cautious about the possibility that people will take quarantine less seriously. The full 14 days remains the safest time period to quarantine, she emphasized.

Asked about quarantine compliance, Howell said it has fluctuated at different times during the pandemic and among different groups of people. For example, young people aged 20 to 29 were showing about 30% compliance, which in some instances led to further cases among so-called “secondary contacts,” a second layer of contacts beyond the person originally exposed to an infected individual.

“People who follow the guidelines don’t have secondary contacts who are sick,” Brannen said.

Most people who quarantine don’t go on to develop the illness, which can cause the public to disregard the guidance, especially those who are asked to quarantine multiple times, Howell noted.

Of the 750 individuals in quarantine in the county during November, 45 developed the illness, or about 6%.

“There’s a risk there — the risk is not zero,” she said.

Public health actions

Appearing before Greene County commissioners two weeks ago, Howell cautioned that the county was headed toward a stay-at-home advisory, as has been imposed in neighboring Clark and Montgomery counties.

“Our trajectory is toward a health advisory,” she said, citing unprecedently high case numbers at the time.

The neighboring counties’ 28-day advisories ask residents to leave home only for essential activities such as work, school, medical care and getting groceries. Analogous to summer heat advisories or tornado watches, they do not carry enforcement provisions, however.

Yet Greene County hasn’t taken that step so far. According to Howell, that’s partly because the county is committed to using “the least restrictive methods” to control the spread of the virus.

In fact, a stay-at-home advisory is a relatively mild measure available to the health department. Local health districts in Ohio are empowered by law to take a variety of measures up to and including ordering a retail business shutdown. Such an action seems to be mostly off the table in Greene County.

“We’re not looking at closures,” Howell said.

Addressing the county commissioners, she acknowledged in response to a question that a business shutdown might be considered if area hospitals were to become overwhelmed by a surge in cases.

“For us, it’s going to be what happens in the hospitals,” she said of the trigger for stronger action.

In place of a stay-at-home advisory or other imposed measures, county health leaders in recent weeks have met with elected officials, business groups and civic organizations to urge greater compliance with masking, social distancing and other protective measures proven to work against the virus.

“We reached out to do an immediate pivot on the numbers,” Howell explained.

She believes the outreach is working. She’s been encouraged by reports of greater mask compliance in retail settings countywide over the past couple of weeks, after a dip in mask-wearing earlier in November. The greater compliance follows the governor’s reissuing of a strengthened mask order on Nov. 13.

In response to a News question, Howell acknowledged that the state mask order and other aspects of the pandemic response have been controversial among some county residents. But she stressed that her agency’s mission was protecting public health based on valid science.

“Social media has politicized the virus. But we are not a political entity,” she said.

Asked why Greene County Public Health seemed to pull back its online messaging about COVID-19 through much of the fall as cases surged, Howell said that the department “changed our strategy” as a result of negative social media activity.

“We’re not going to feed that animosity,” she said of comments on the department’s social media platform.

The retooled strategy focuses on one-to-one outreach to local groups, and targeted messaging in partnership with schools, mayors, business and civic groups and others, she said.

Of the shift away from social media, Howell added that some public messaging has the potential to feed anxiety and PTSD among county residents, noting the pandemic’s ongoing “physical, economic and psychological implications.”

“This is also a disaster,” she said of the pandemic, likening it to a tornado or other traumatic event.

But there’s light at the end of the tunnel, she added.

Greene County Public Health is currently coordinating with the state on the distribution of the first doses of new COVID-19 vaccines. Approval for two new vaccines is expected from the FDA this week, with distribution among priority groups slated to begin in Ohio on Dec. 15, Gov. Mike DeWine announced at a press briefing last Friday.

Early vaccine doses will cover some, though initially not all, residents and staff at nursing homes and other long-term care facilities, frontline health care workers, first responders and other priority groups. Younger and healthier residents should expect to wait until as late as this summer to be vaccinated, according to Howell. Some protective measures will need to remain in place until that time, she added.

“This pandemic is coming to an end,” she said. “We’re not there yet, but it’s coming.”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.