Julia Reichert, known as the “godmother of American independent documentaries,” had a career in filmmaking that spanned more than 50 years. (Photo by Steven Bognar)

IN MEMORIAM | Julia Reichert’s legacy in truth, film

- Published: December 16, 2022

Update May 4, 2023: A memorial service for award-winning filmmaker Julia Reichert, who died Dec. 1, will take place Saturday, May 6, at 4 p.m., under a large tent to be erected in the “horseshoe” in front of Antioch’s Main building. The service was originally scheduled in December, but had to be rescheduled because of COVID.

The May 6 service will feature movie clips, speakers and music performed by the World House Choir. A reception will follow. Everyone is welcome. Some dedicated accessible parking spaces are available on Livermore Street near the horseshoe.

Longtime villager, filmmaker and activist Julia Reichert died Thursday, Dec. 1 at her Yellow Springs home after living with cancer. She was 76.

A documentarian with a career spanning more than 50 years, Reichert’s oeuvre includes more than two dozen works as director and producer. Her work in film will be remembered for holding a megaphone to the voices of women and the working class — a thematic thread that ran through many of her most important works.

Her debut film, “Growing Up Female,” was created while she was a student at Antioch College, in tandem with fellow student Jim Klein, with whom Reichert would go on to create several more documentaries. The film, released in 1971, followed five girls and women as they spoke about navigating the world in the face of societal expectations thrust upon them by the public at large and in their own relationships.

Considered one of the first films of the women’s liberation movement, “Growing Up Female” was selected in 2011 for the National Film Registry, an arm of the Library of Congress that names 25 films per year that showcase “the range and diversity of American film heritage,” according to the organization’s web site.

In 1976, Reichert made “Union Maids” with Klein and Miles Mogulescu. Produced in Chicago, Illinois, on what many filmmakers would consider a shoestring budget of $12,500, the documentary captured interviews with three women who fought to form industrial labor unions in the early 20th century. Reichert told the News in 2018 that the filmmakers were surprised when “Union Maids” went on to earn an Academy Award nomination for “Best Documentary Feature.”

“It was a huge hit in the women’s, socialist and labor movements,” Reichert told the News. “It was crazy. It must have been the least expensive film ever nominated for an Academy Award.”

Another Oscar nomination followed for 1983’s “Seeing Red,” which Reichert also completed with Klein and a $250,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. The film, which aimed to shed light on the politics of American Communists — particularly with regard to labor activism and reform — included interviews with more than 400 people. A New York Times obituary for Reichert called the film “arguably the most sympathetic portrayal of American Communists ever put on screen.”

Reichert’s next nomination came for the 2009 film “The Last Truck: Closing of a GM Plant,” which she created with her longtime collaborator and partner Steven Bognar. The film followed workers at a closing General Motors plant in Moraine, Ohio. The filmmaking pair returned to Moraine from 2015 to 2017 to again follow the lives of workers in the Moraine Assembly plant — only now, instead of housing GM, the factory housed Chinese company Fuyao.

The resulting documentary, “American Factory,” captured the cultural and political clashes between Chinese workers and supervisors and former GM employees, and their struggles to understand each other and adjust expectations about how to work together.

“This film sits in the shoes of those from different sides,” Reichert told the News in 2019, after she and Bognar won a directing award for the documentary at the Sundance Film Festival. “It leaves you confounded. It leaves you thinking.”

Film critics, whose reviews of “American Factory” were overwhelmingly glowing, agreed with Reichert’s assessment; many lauded the intimacy and vulnerability, the sometimes brazen moments of honesty and even cruelty captured by the film crew.

“The access the filmmakers secured was remarkable,” wrote Mahnola Dargis of the New York Times. “Bognar and Reichert spent a number of years making ‘American Factory,’ a commitment that’s evident in its layered storytelling and the trust they earned.”

The film, backed by Barack and Michelle Obama’s production company Higher Ground Productions and later distributed by Netflix, won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 2019.

Accepting the award, Reichert said: “Working people have it harder and harder these days, and we believe that things will get better when workers of the world unite.”

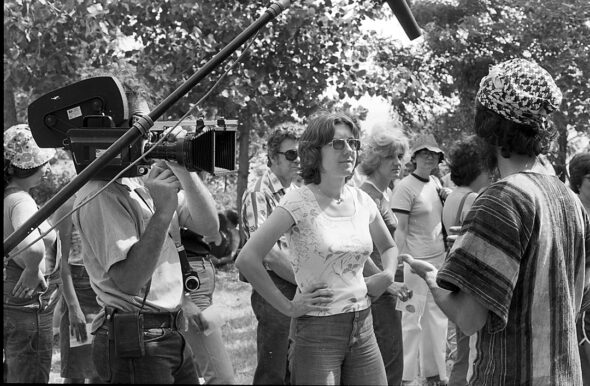

Julia Reichert, known as the “godmother of American independent documentaries,”

had a career in filmmaking that spanned more than 50 years. She’s pictured in 2006

while filming “A Lion in the House.” (Photo by Steven Bognar)

The beginning of a life’s work

Reichert came to Yellow Springs in the 1960s to attend Antioch College. The daughter of a working-class family from Bordenton, New Jersey, Reichert told the News in 2018 that she didn’t know anyone in her hometown who went to college other than educators and the local doctor. Nevertheless, she was attracted to Antioch because of its co-op program, which would allow her to earn money while she studied, and see the world in the process.

A Republican from a family of other Republicans when she entered college, Reichert found that her fellow students were involved in the anti-war and women’s liberation movements. Reichert said her own politics shifted after long conversations with her roommate, a Jewish woman whose parents were members of the Communist party.

“You switch fast when you hit the big world,” Reichert said.

Her time at Antioch also changed her views on her own background. Though many of her fellow students came from college-educated families with money, her own father was a butcher — a fact she initially obscured from her classmates. Soon, however, her studies taught her more about the historical importance of the working class in bringing about social change and the cultural and structural obstacles faced by women.

“You realized it wasn’t just you — it was the system,” Reichert said in 2018.

At the same time, Reichert began cultivating interests in photography and radio, spending time in the darkroom and hosting a weekly WYSO radio show, “The Single Girl,” often credited as the nation’s first feminist radio program. These interests dovetailed into filmmaking, and led to the creation of “Growing Up Female” with Jim Klein, with whom she collaborated often on film projects while both were students and whom she later married. The film, Reichert said, was simply meant to document the experiences and feelings of its five female subjects without introducing abstract ideas.

“It wasn’t a film about the women’s movement,” she said. “It was just probing these women, asking them how they felt.”

“Growing Up Female,” released following Reichert’s graduation from Antioch College, became a success not only because of the skill and care exhibited by the filmmakers, but also because of their hard work in getting the word out about the film. Eschewing the traditional route of hiring a distributor, which would deplete their financial resources and lessen their control over their own work, Reichert and Klein advertised “Growing Up Female” via posters they made themselves and by sending film reels off to interested theaters from the local post office.

Based on their own experiences with self-distribution, -Reichert and Klein, along with fellow feminist filmmakers Amalie R. Rothschild and Liane Brandon launched New Day Films, a film distribution cooperative in 1971.

“The whole idea of distribution was to help the women’s movement grow,” Reichert and Brandon wrote for the New Day Films website. “We could watch the women’s movement spread across the country just by who was ordering our films.”

The cooperative continues to this day, with 140 member-owners. Klein wrote on the New Day website that though Reichert will be remembered for her “wonderful films,” her work building connections and opportunities for independent filmmakers will also “live on.”

“Before DIY became a thing, Julia lived the idea,” Klein wrote. “She even wrote a manual titled ‘Doing it Yourself’ in 1977 that helped generations of filmmakers get their work out.”

Educating future filmmakers

Following the releases of “Union Maids” and “Seeing Red,” Reichert and Klein, by now the parents of young Lela, began teaching film and production classes at Wright State University. While their marriage dissolved a few years later, the two continued working on each other’s films and team-teaching at Wright State; Reichert’s tenure there would span 28 years.

Stuart McDowell, professor emeritus and former chair of the film department at Wright State, said this week that Reichert’s impact on students’ lives would be felt forever.

“The world is such a better place because of Julia’s contribution — her teaching, her love of life, her love of family and students and alumni and fellow filmmakers,” McDowell said.

Remembering his time studying under Reichert, Jonathan McNeil, a Wright State graduate and current manager of The Neon movie theater in Dayton, said Reichert showed students a different side of documentaries.

“For so many of us that were going to film school, documentaries were foreign to us — they were on PBS and about nature,” McNeil said. “Julia introduced documentaries as reflections of humanity, she taught us to question and explore; to do that, you had to be honest with yourself. You had to know about yourself before you could ask questions of others.”

McNeil said Reichert’s teaching ethos expanded beyond the courses she taught on documentaries. Reichert would sit in on editing sessions, give feedback and work to build connections between students and people in the film industry.

“She was always there,” McNeil said. “It wasn’t any kind of glamorous position. It was important to her to see students through to the end.”

Reichert’s impact on students lived both inside and outside of the film department. Looking to teach across content areas and lift the voices and contributions of women, Reichert proposed classes such as “Women in Film,” a class that served both film students and students from the Women and Gender Studies Department. Kelli Zaytoun, coordinator of Women and Gender Studies, said Reichert had “extraordinary vision.” According to Zaytoun, Reichert would arrange virtual visits from filmmakers for her students — before Skype or Zoom.

“Reichert’s work as a teacher was like her filmmaking: invested, hands-on and collaborative,” Zaytoun said. “She modeled what it means to be guided by a sense of ethics in both work and in daily living.”

For Reichert, the end of her mentorship was not graduation. In a statement on behalf of the film school, Joe Deer, artistic director of the Department of Theatre, Dance and Motion Pictures, said Reichert was a “rare, generous, force of nature,” who engaged her students long after they were in her Wright State classroom.

“As I look at the credits for her films with partners Steven Bognar and Jim Klein, I see names of hundreds of then-current and former students, staff and teaching colleagues in key production roles,” Deer said. “That hands-on practical apprenticeship meant that the Dayton film community was constantly engaged with the highest level films.”

Julia Reichert, center, was photographed on site interviewing subjects during the filming of Seeing Red, a documentary about current and former U.S. Communists, which she co-directed with Jim Klein in 1983. (Photo by Tony Heriza; used with permission)

A hometown artist

The kind of success that Reichert found with her films might have convinced another filmmaker to pull up her stakes and settle in Hollywood — but Reichert stayed in the Miami Valley for the rest of her life, holding up her lens to the lives of people in the Midwest.

“We need filmmakers, radio people, whatever — activists in the Midwest,” Reichert told WYSO last year. “We need people who are interested in examining and changing the world. We need to put down roots so we can be a voice where there is no voice.”

Her film work in the new millennium, much of which she created with her collaborator and partner, Steven Bognar, speaks to her passion for amplifying voices near her home: The 2006 film “A Lion in the House” follows five children with pediatric cancer and their families, along with doctors and nurses at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. The film won a Primetime Emmy for Exceptional Merit in Nonfiction Filmmaking in 2007. Following the release of “The Last Truck” in 2009, Reichert and Bognar produced the 18-minute film “Sparkle,” about Dayton Contemporary Dance Company dancer Sheri Williams, and the 2016 film “Making Morning Star,” about the Cincinnati Opera.

Yellow Springs audiences were often some of the first to view Reichert’s work, and were always enthusiastic supporters when her films debuted at the Little Art Theatre. Jenny Cowperthwaite Ruka, former owner and executive director of the Little Art, wrote to the News this week that she first met Reichert when she began working at the theater at the age of 16 and the theater screened “Growing Up Female.” Cowperthwaite Ruka noted that Reichert and her collaborators were almost always on hand to interact with audiences at local screenings through Q&A sessions.

“In fact, my favorite times with Julia and Steve were when they’d screen their latest work-in-progress at the Little Art to a select audience to obtain their honest feedback and see what was working in the film and what was not,” Cowperthwaite Ruka wrote. “The fascinating complexity of filmmaking and storytelling was always revealed to me during these screenings.”

Cowperthwaite Ruka added that Reichert was a “deep and emphatic listener” and a “compassionate, ‘ear to heart’ filmmaker.”

“She truly cared about the issues and the people in her films, and she never embellished or manipulated her work — her staunch integrity wouldn’t allow that. She was an honest filmmaker,” she wrote. “She was deeply revered, loved and respected throughout the filmmaking community and earned the well-deserved title ‘The Godmother of Independent Documentaries.’”

In April 2022, local community members who had filled the seats of the Little Art over the years watching Reichert’s films found themselves not only in the auditorium, but on the big screen. A multiple-night run of “Dave Chappelle in Real Life,” which Reichert and Bognar filmed in Yellow Springs in summer 2020 during the height of the pandemic, opened with a free, invitation-only screening of the documentary. The film brought applause and cheers from those in the audience who recognized themselves, their friends and their neighbors in the documentary.

On the film’s opening evening, Reichert told the audience that she and Bognar were “very proud” of the film, but noted that the documentary was especially important to her, as it would likely be her final work.

“This was a work of love and respect,” Reichert told the audience. “And we are just so glad to finally bring it to our hometown.”

A memorial service for Reichert will be held Friday, Dec. 9, beginning at 5 p.m., at First Presbyterian Church, with a reception to follow. Masks are encouraged. At the service, the World House Choir will sing the song “My Story,” which was commissioned by Reichert for “Seeing Red” and written and originally performed by composer, activist and founder of a cappella group Sweet Honey in the Rock, Bernice Johnson Reagon.

Interment will be at Woodland Cemetery in Dayton on Saturday, Dec. 10, at 10 a.m.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.