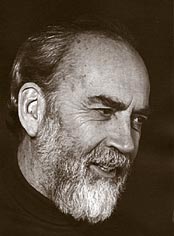

Meredith ‘Dal’ Dallas

- Published: November 11, 2010

On Nov. 1, shortly after 2 a.m., Meredith Dallas, surrounded by family, died peacefully at the Friends Care Center, where he had been living for the past year.

On Nov. 1, shortly after 2 a.m., Meredith Dallas, surrounded by family, died peacefully at the Friends Care Center, where he had been living for the past year.

The third child and second son of a factory foreman, Meredith Eugene Dallas, or Dal, as his friends and colleagues affectionately called him, was born on Dec. 3, 1916, in Detroit, Mich., to William and Ethel Dallas who would go on to have six children. When his older brother died at the age nine, the 6-year-old Meredith became the vessel of his father’s ambition — that his oldest son grow up to be a Methodist minister. This ambition dovetailed nicely with the influence Detroit’s Central Methodist Church had on the young Meredith. Of particular influence were people of social conscience and national renown, like educator and civil rights leader Mary Bethune, who would on occasion speak to the congregation. Through the church, Meredith was active in the Young People’s League, an organization that examined issues of race and labor in America (an organization that would later be labeled by Joe McCarthy as a Communist front). Politically and philosophically influenced by these activities, Meredith became a pacifist by the time he completed high school.

Meredith had not considered going to college, but when a recruiter from Albion College, a Methodist school, visited Central and asked the minister if he would recommend a potential student, the minister recommended Meredith. When his older sister, Beatrice, a nurse, offered financial support, Meredith enrolled in Albion. It was there that Dal (the nickname was born at Albion and stuck) met George Dewey, who would become a close friend for the next 60 years. It was also at Albion that Dal met Willa Louise Winter. Dal, a philosophy and speech major, was asked in his senior year to take over a freshman philosophy course when a professor took ill. Willa was a student in that class. Both student and teacher were soon smitten.

After graduating from Albion in 1939, Dal pursued a graduate degree in divinity at Union Theological Seminary. At Union he joined a group of activist seminarians that believed that Christ’s work was best learned as practiced in the trenches, rather than studied in the safe confines of the ivory tower. They created a settlement house in the slums of Newark, then another settlement house in Harlem. They took in homeless people and drunks off the street, fed them, clothed them and tried to find them work. Already infected with the zeal of service, and deeply in love with her beau, Willa was eager to leave Albion when Dal asked her to join their Christian commune in Newark.

In 1940, at the beginning of World War II, Dal was one of eight seminarians who refused to register for the draft. As seminarians they were exempt from service; as pacifists they felt compelled to make a public stand. How they would be charged in federal court was not known; if found guilty of treason, there was even talk of death sentences. The day the “Union Eight” were sentenced to serve a year and a day in the Danbury, Conn. federal penitentiary, they were front-page news in The New York Times. Dal and Willa wanted to marry before Dal was sent away, but because Dal was a felon, they couldn’t get a license in either the state of New York or Connecticut. They were able to get a license in Detroit, but the elders of Central Methodist would not allow the ceremony to take place in the church. So the minister of Central performed the ceremony in his home. When the newlyweds left the parsonage, photographers literally jumped out of the bushes. The next morning their wedding photograph was on the front page of the Detroit Free Press.

At the Danbury penitentiary, the Union Eight, through acts of civil disobedience such as deliberately sitting in the black section during meals, helped integrate the prison’s dining hall. For these acts they were frequently put in solitary confinement.

While at Danbury, Dal learned basic nursing skills and worked as the prison’s operating room nurse. Upon his release, the prison authorities registered him for the draft. When his number came up, Dal refused to serve. Again he was arrested. This time he was sent to a boy’s detention center in Ashland, Ky., to head up the facility’s infirmary. Wanting to be near Dal, Willa and their young daughter, Barrie, born in 1942, moved into Willa’s parents’ house in Portsmouth, Ohio. A peace conference in 1943 drew Willa to the village of Yellow Springs, a hundred miles to the north. She liked the place enough to move there, and in 1945 Dal was paroled to his family in Yellow Springs.

Dal’s first job in Yellow Springs was doing blood chemistry analysis for the Fels Institute. A year later, Dal became assistant to the dean at Antioch College. He soon found himself an avid thespian with the Antioch Area Theatre. In pursuit of a career in theater, Dal was awarded a full scholarship with stipend to the masters program in theater at Case Western Reserve, so the family, which now included their second daughter, Patti, moved to Cleveland for two years. After his graduate work, Dal accepted a faculty position in Antioch’s theater department. Dal and Willa’s last two children, Wendy and Tony, were soon born in Yellow Springs.

Through theater and teaching, Dal found his purpose in life. Having given up on the ministry (because God, he said, had never spoken to him), Dal found his church in the Antioch Area Theatre. Dal, along with Paul Treichler and Arthur Lithgow (known around Antioch in the 1950s as “The Triumvirate”), went on to shape Antioch’s theater department into a world-class program. Dal was a founding director and actor with Antioch’s Shakespeare Under the Stars, which opened in 1952 — its stage built off the massive stone steps of the Main Building. Between 1952 and 1958, a company of professional actors, students and villagers presented all of Shakespeare’s plays. This was the first time in the world that all of Shakespeare’s plays had been presented one after the other in one location. Then in 1961, using a similar mix of professional actors and students, Dal spearheaded six years of plays in the Antioch Amphitheatre — presenting five shows a summer, ranging from the Greeks and Shakespeare to Genet and Beckett. Dal usually directed three of the shows and acted in a fourth — sometimes directing and acting simultaneously.

As an actor and director Dal was superlative. The two parts for which he is most fondly remembered are Willy Lohman, in Death of a Salesman, and Malvolio, in Twelfth Night, a role he first performed for Shakespeare Under the Stars, then reprised in 1958 in Central Park for Joseph Papp’s Public Theatre, then later in the amphitheatre. As a director, actor and teacher, Dal had lasting influence on scores of students who went on to professional careers in the field and were instrumental in starting up the Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park; the Actors Theatre of Louisville; the American Conservatory Theatre; the Virginia Stage Company; the Shared Experience Theatre Company in London, England; Otrabanda and Talking Band.

In the 1970s, influenced by the works of Carl Rogers, Fritz Pearls and others, Dal became involved in the human potential movement. Looking towards a second career upon retiring from Antioch, in 1976 he was granted a PhD in Gestalt therapy through the Union for Experimenting Colleges and Universities. Along with counseling individuals and couples, Dal combined psychotherapy with theatre for dream workshops, in which participants plumbed the gestalt of their dreams by casting and directing others in “staged” versions of their dreams. Dal worked as a psychotherapist for the next 20 years of his life.

Dal was an authentic man who thought deeply about the meaning of a life, and in that vein struggled to walk his talk. His impact as an artist and human being was substantial and spanned decades. He was deeply loved by many, and by many he is already deeply missed.

He is survived by his sisters Marjorie Kammer and Eunice George and a large extended family; his widow, Willa Dallas, and their children and partners, Barrie and Peter Grenell, Patti Dallas and Marianne MacQueen, Wendy Dallas and Anne Block, and Tony Dallas and Migiwa Orimo; grandchildren Alex Grenell, Nathania Dallas and Paloma Dallas and her husband, JuanSi González, and their daughter, Camila Dallas González.

A memorial to celebrate the life of Meredith Dallas will be held in the Glen Helen Building on June 19, Father’s Day, the last day of the Antioch College Reunion, at 2 p.m.

2 Responses to “Meredith ‘Dal’ Dallas”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

My first term at Antioch, Dal casted me in the Trial of the Catonsville nine about the Bergen brothers and seven others pouring blood on selective service files. That was 1971 and the War in Viet Nam was raging. That play had many performances in the community followed by discussion about that War. I was emotionally struggling with separating from my father and needing him to become more demonstrative of his love fo me. I met with Dal and was tearful and explained that I didn’t think I could do the role in which he had casted me for that night’s performance. He explained that it had been his decision to cast me and that he believed I could do it. That night I channeled those raw emotions into my character and for once acted.

I knew that our play was significant but only after reading that Dal went to prison for being a conscientious objector, did I recognize the extent of its significance.

I am with my 17 yo son at a soccer tournament in Cincinnati, trying to arrange a visit with Dal on our way back to Kalamazoo, MI when I learned of his passing. When I turned 18, I had applied to be a CO, but the draft lottery gave me a safe number so never appeared before the Selective Service Board to explain/defend my beliefs. Months later the War escalated and I joined the protest at Wright-Paterson AFB and spent five day in jail. Fortunately that police record didn’t prevent me from attending medical school and obtaining licensure.

Dal, thanks for casting me and teaching me some important life lesions.

James Voigt, MD

(269)220-9169

Peace