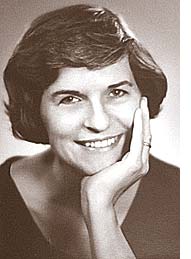

Willa Dallas

- Published: June 21, 2012

Willa Louise Winter Dallas was born Oct. 12, 1919, in Portsmouth, Ohio. Her father, Frederick Benjamin Winter, was a mason who operated a feed store on Front Street and served as a river watcher, monitoring the level of the Ohio River. Her mother, Roma Belle Matteson Winter, was a music teacher and choir director. While a freshman at Albion College in Michigan, Willa came to know Meredith Dallas, a senior, and a teacher’s assistant in her philosophy class. When at the beginning of the term the philosophy teacher took ill, Meredith took over the class. They were soon both smitten, he with her good looks and agile prowess on the hockey field.

After he graduated, Meredith went on to Union Seminary in New York City. In the summer of 1940, he asked Willa to join him and other pacifist divinity students and their partners in what they unofficially called the “Newark Ashram.” Inspired by Gandhi and Catholic worker communities, they strove to live a more meaningful Christian life. They took jobs in factories, pooled their money, and took in homeless people and teenagers in trouble, putting them up in the ashram and taking them out to a farm in New Jersey for the wholesome environment of picking apples and generally operating the farm. David Dellinger, Bayard Rustin and A.J. Muste are the more famous names of their associates during this early commitment to pacifism and social justice. Eight of the students at Union Theological Seminary lived their pacifism by refusing to register for the draft, even though as seminarians they would have been exempt from service. The “Union Eight,” as they became known in the New York Times, were sentenced to a year and a day in Danbury Federal Prison. Willa and Meredith got married Oct. 26, 1940, two weeks before Meredith began serving his term. Willa continued to live and work at the Newark Ashram. Friendships forged in Newark lasted decades. Willa’s experience with the ashram transformed her into a lifelong social activist.

Their first child, Barbara (Barrie), was born in Newark in 1942, and when Meredith again refused to register for the draft, he was sent back to prison, this time to Ashland, Ky., where the warden asked him to set up the medical clinic at a youth detention camp, across the Ohio River from Willa’s family home in Portsmouth, Ohio. In 1944, Willa attended a Quaker conference in Yellow Springs. She was so taken with the village she moved there and arranged for Meredith to be paroled to Fels Institute; he later migrated to the dean’s office at Antioch College. During this time, twins Patricia and Pamela were born (Pam died ten weeks later), and Meredith, now “Dal,” became involved with the Antioch Players at the Opera House. In 1946 they moved to Cleveland for one year, while Dal earned his M.A. in theater at Western Reserve. The family returned to Yellow Springs when Dal was hired to teach theater at Antioch — which he did for the next 30 years. Willa had originally thought she was going to be a minister’s wife, but as partner to a drama professor, she played a similar role, nurturing students and many others with teas, backyard cookouts, dinners and parties — serving up great quantities of sloppy joes and Spanish rice at final technical rehearsals and cast parties. Wendy Rae was born in 1948, and Tony in 1951.

Willa packed up the household when Dal took work in summer theaters in Martha’s Vineyard, Hyde Park and Wellesley; one summer, the entire family was hired to work at an Easter Seal camp in Boulder Creek, Calif. In 1958 the family moved to Brooklyn for a year while Dal, on sabbatical from Antioch, worked as an actor with Shakespeare in the Park and the Phoenix Theatre.

Willa was prodigious in her ability to connect people, and she was an ace at finding temporary housing and forming friendships wherever she was. She loved to sing. On car trips with the family, the car would float down the highway on rousing renditions of camp and folk songs. And for a number of years in the 1950s, “village sings” were held in the Dallas’s back yard, often led by Walter Anderson, and what seemed like half the town would gather around a bonfire in the glow of mayonnaise jars with lit candles hanging from trees, singing folk songs and spirituals.

Willa’s involvement with the civil rights movement included, for a number of years, raising money and collecting clothing for the poor in the Mississippi Delta. She was at the 1963 March for Freedom and Jobs in Washington, DC. In 1964 she was a regular picketer of Gegner’s barbershop. And when over 100 students from Central State, Wilberforce and Antioch created a human blockade sitting in the middle of Xenia Avenue and were wrangled up by Greene County deputies and shoved into paddy wagons, Willa was there to do her bit. She stood by the paddy wagon door: when officers turned around to grab up more students, she would pull students who were already in the paddy wagon off. When she spied an officer bending a student’s arm behind his back, she told him, “You don’t have to do that!” He responded, “You, too, lady,” then threw her into the paddy wagon. That was not the last time Willa spent a night in prison.

In 1965, she, along with Dal, Wendy and Patti, participated in the march from Selma to Montgomery. Following the Selma march, Willa considered moving the family to Alabama. Wherever the moral fight was, she wanted to be on the frontline. Instead, as part of a project co-sponsored by the Southern Student Project Committee and the American Friends Service Committee, she found homes for six African-American high school students from Alabama in Yellow Springs so they could experience for one year a multi-racial education. This was thought to be part of the groundwork for rebuilding a South in racial transition. Two of those teenagers moved into the Dallas household. Willa was instrumental in creating the annual Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. march in Yellow Springs. With the “Alternatives to Violence” program, she organized and carried out nonviolence training in prisons. She spent many hours on the telephone encouraging people to come to the concerts to benefit Friends Music Camp, or to participate in Oxfam rice and beans dinners; she made sure that Senior Center bridge tables would have four players; and in the 1980s Willa and Dal started the Dayton chapter of PFLAG (Parents and Friends of Lesbians And Gays). Willa’s decades of community and advocacy work earned her entry into the annual Greene County Women’s Hall of Fame, and her work with PFLAG earned her the Human Rights Commission Award. Once when asked what was most important to her, she replied, “Helping one another.”

Willa is survived by her children, Barbara Dallas Grenell and her husband Peter; Patricia Dallas and her partner, Marianne McQueen; Wendy Dallas and her wife, Anne Block; Tony Dallas and his wife, Migiwa Orimo; grandchildren Paloma Dallas and her husband, Juan-Si Gonzalez, Nathania Dallas, and Alexander Grenell; great-grandchild Camila Dallas-Gonzalez; and nephew Kenneth Winter.

A memorial program will be held at the Glen Helen Building on Sunday, September 30. In lieu of flowers, donations in Willa Dallas’s memory may be made to any number of organizations that work for the causes that were so dear to her: peace, justice, human potential and human rights.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.