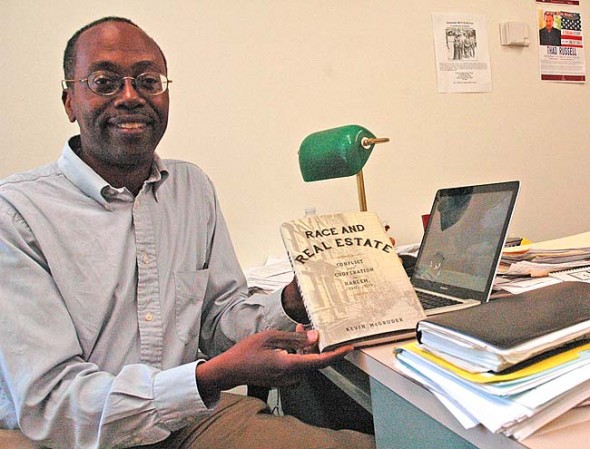

Kevin McGruder, assistant professor of history at Antioch College, will discuss his latest book, Race and Real Estate: Conflict and Cooperation in Harlem 1890–1920, on Tuesday, Aug. 4. at 7 p.m. at McGregor 113 on the college campus. He will also sign copies of this book, which was recently published by Columbia University Press. (Photo By diane chiddister)

Antioch College historian eyes race, community

- Published: August 6, 2015

When most historians have written about Harlem, they’ve focused on the hostility of early white residents when blacks began moving into their upper Manhattan neighborhood, and the area’s evolution into an African-American ghetto known for its violence and dysfunction.

But Kevin McGruder, assistant professor of history at Antioch College, has a different, more nuanced story to tell about the neighborhood he came to love as a resident, churchgoer, business owner and historian. Specifically, he tells the story of early white Harlem residents who appeared to hold diverse views of their African-American neighbors. And he believes that Harlem was originally a place of aspiration for the blacks who moved there, who created churches, neighborhood organizations and other components of community.

“The ghetto emphasis focuses on disarray,” McGruder said in an interview last week. “I’m not saying that didn’t happen, but there hasn’t been enough emphasis on community formation. What was the goal of people moving there?”

For the past several years, McGruder has studied old newspapers and historical documents to find answers to that question. And the result of that research, Race and Real Estate: Conflict and Cooperation in Harlem, 1890 to 1920, was published last month by the Columbia University Press.

McGruder will discuss and sign copies of his recently published book Tuesday, Aug. 4 at 7 p.m. at McGregor 113 on the Antioch College campus. The book is an extension of his doctoral dissertation.

The dissertation grew out of McGruder’s longtime interests in real estate, Harlem and African-American history, he said in a recent interview. Before getting his Ph.D. from the City University of New York’s Graduate Center, he had worked in community development nonprofits in Cleveland and New York City, along with serving as director of real estate of the historic Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, of which he’s a member. He was also co-author of a previous book, Witness: Two Hundred Years of African-American Faith and Practice in the Abyssinian Baptist Church.

Research for Race and Real Estate involved combing through many historical documents in the City Registry in New York, supplemented by stories in newspapers of the time, which he found on microfilm in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library, where he was scholar in residence during 2011–2012. Not surprisingly, as a historian, having access to so many original documents “was paradise,” McGruder said.

What McGruder found in his research was that Harlem at the turn of the century was a place of some fluidity for blacks, many of whom moved there from other African-American enclaves, such as Greenwich Village and the district now known as Chelsea, formerly the Tenderloin. Harlem was at the time on the edge of developed Manhattan and was surrounded by fields, so that the neighborhood provided a more expansive, country-like atmosphere compared to the inner city.

While the conventional history of the African-American migration to Harlem is that whites responded with hostility, McGruder was surprised to find that, while there was hostility, there was also evidence of cooperation between the races. For instance, bank loans were largely unavailable to blacks, so that those seeking to buy homes depended on getting loans from the white property sellers, who apparently didn’t resist selling to blacks. The evidence of fluidity and cooperation between blacks and whites indicates a time when race relations were considerably better than they became later in the 20th century, McGruder believes.

This complex relationship between the races at that time seems to belie the assumption that difficult social problems such as race relations inevitably get better with time, McGruder said. Rather, his book shows that progress in race relations ebbs and flows over time, with more mutual understanding and cooperation evident in some periods than others.

“The notion that things get better just because time has passed — there’s no evidence of that,” he said.

In Race and Real Estate, the story of how blacks and whites interacted as neighbors and business associates in Harlem is told through the perspectives of four actual individuals. There was white businessman Henry Koch, retired white policeman John Taylor, African-American Pastor Hutchins Bishop and Phillip Payton, an African American who became a leading real estate agent catering to black families.

Telling the story through the perspectives of these actual individuals “makes the story more real,” McGruder said.

Around the time McGruder finished the book, he was hired by Antioch College. Coming to Yellow Springs, he took to heart the stories of those early African-American families establishing community in a new location. McGruder, too, sought membership in a church community, the Central Chapel A.M.E. Church, and also became a member of the World House Choir, to deepen the connection to his new home.

While McGruder is sinking roots into his new home, he will always have a soft spot for Harlem, where he maintains a membership in the Abyssinian Church. And it’s likely he’ll return often, as his next project is a biography of Phillip Payton, the realtor who made a difference to many African-American families when he helped them find homes in turn-of-the-century Harlem.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.