Village filmmaker is honored by industry

- Published: December 13, 2018

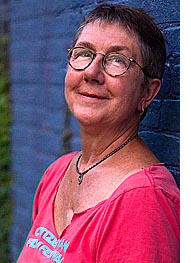

Local filmmaker Julia Reichert will receive the International Documentary Association’s Career Achievement Award this Saturday in Los Angeles. The award goes to a filmmaker each year who has made a substantial contribution to the field of documentary films. (Submitted photo by Eryn Montgomery)

Each year the International Documentary Association, a professional group for documentary filmmakers, selects a filmmaker to receive its highest honor, the Career Achievement Award. The award spotlights someone who has had a significant impact on filmmaking, according to IDA Executive Director Simon Kilmurry. The process for choosing the winner is intense, with the IDA board considering seven or eight esteemed documentarians before making a decision. But this year, the board voted unanimously, he said. The award will be given to Yellow Springs filmmaker Julia Reichert.

“Julia’s work more than qualifies,” Kilmurry said in a phone interview this week. When he watched several of Reichert’s films recently, he said, “Something struck me. It was how intensely patriotic and democratic the films are, in the best sense of those words. The films are calling us to be our best selves.”

Reichert is also singular in her choice of subject, he said, noting that many of her films spotlight women, blue-collar workers or others who exist outside American power centers. By focusing her camera on these often-overlooked lives, “her films show what documentaries do well, by lifting up lives that have been marginalized.”

As an example, Kilmurry pointed to “The Last Truck: Closing of a GM Plant,” the 2009 film Reichert and Steven Bognar made that followed the lives of workers when a Moraine GM plant closed down.

“No one else would have made that film,” he said, calling Reichert’s body of work “a testament to her commitment to those stories, the ones we don’t focus on often enough.”

Well-known documentary maker Barbara Kopple, who has won two Academy Awards for her work, including for the film “Harlan County, USA,” agrees that Reichert is an inspired choice for the award.

“The choice of Julia for this award is extraordinary. I can’t think of anyone who deserves it more,” Kopple said in a phone interview Tuesday. “The stories she tells tend to be about people whose power has been taken from them, whether women or working people. Her films really matter.”

For Reichert, receiving the award is especially meaningful because it’s an honor bestowed by her peers, fellow documentary filmmakers.

“They know what it’s like to make a documentary, how hard it is,” she said this week. “They know that when it comes together, it’s like a little miracle. For my peers to recognize me — it’s great. It’s humbling.”

Reichert will receive her award this Saturday, Dec. 8, at the annual IDA awards ceremony at the Paramount Theater in Los Angeles.

Her films themselves have already received a bevy of recognitions. Three have been nominated for an Academy Award, one received an Emmy and one was chosen for the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress, among other honors. But the greatest reward has been the opportunity she’s been given to step inside other worlds when she makes a documentary, she said this week.

“I have the opportunity to learn about all these different worlds, to be immersed in them,” she said. While all of her films have focused on American topics, “there have been all these different cultures. It’s like a passport, opening doors.”

And the work itself is a constant challenge, she said. The challenges include finding the narrative within each topic, editing and distilling hundreds of hours of film down to its essence, then distributing the finished film and taking it into the world.

At that point, she gets to “see people’s faces as they watch,” she said. “It is all so challenging and so enriching.”

It started at Antioch

A little more than 50 years ago, it would have been improbable to imagine that Reichert would someday be honored by an international body of documentary filmmakers.

She was a girl from a small New Jersey town who didn’t know anyone who went to college other than her teachers and the local doctor. She was the daughter of a man who never finished eighth grade, the butcher at the local grocery. But Reichert was determined to learn, to get out of town, to go to college. On her own when she was in high school, Reichert began sending away for college catalogs, studying them at night before bed. Antioch attracted her because of the co-op program, she said. She’d always made her own money and wanted to continue to do so. And co-op would allow her to see the world.

“The whole basis of what I am started right over there,” she said last weekend in her Xenia Avenue home, pointing to the Antioch College campus.

Reichert arrived at Antioch in the mid-1960s, a heady time with the nascent women’s liberation and anti-war movements energizing and roiling the campus. While Reichert’s family was white working-class Republican, her roommate freshman year was a Jewish woman, whose parents were members of the Communist party. The two had intense conversations that covered everything, including politics. Initially a Goldwater Republican, Reichert by that fall’s presidential election was passing out pamphlets for Lyndon Johnson.

“You switch fast when you hit the big world,” she said.

Still, Antioch offered considerable challenges. At first she felt out of place, as her classmates all seemed to have fathers who were engineers or doctors or lawyers. Initially she felt shame over her working class background, she said, telling others at a freshmen gathering that she was the daughter of a grocery store manager rather than a butcher. But as she learned in classes about the critical role of the working class in bringing about historical change, she began to reclaim pride in her background.

And through consciousness raising groups, as she and other young women shared their stories, Reichert became far more aware of the cultural and structural obstacles faced by women.

“You realized that it wasn’t just you who didn’t raise her hand in class. It wasn’t just you who didn’t dream big,” she said. “You realized it wasn’t just you — it was the system.”

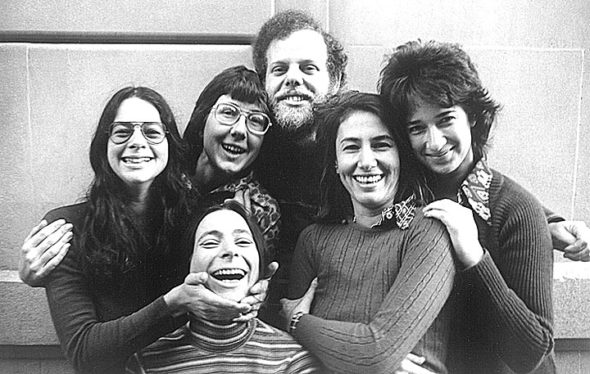

These discoveries led to Reichert’s first film, “Growing Up Female.” She needed a senior project for the filmmaking class she was taking, having found that her interests in photography and radio dovetailed perfectly into making films. She’d also been inspired by seeing experimental films on campus, and by the young film teacher, only 24 himself, who encouraged his students to get started.

“He said, just pick up a camera and shoot. He was all about self-expression,” she said.

She did so, often collaborating with a fellow film class student Jim Klein. For her senior project, Reichert and Klein decided to interview five women of various ages about their lives, and the forces that shaped them, including advertising, music, role models and marriage. It was a simple idea, she said, with a focus on human experience rather than abstract ideas.

“It wasn’t a film about the women’s movement,” she said. “It was just probing these women, asking them how they felt.”

After completing the film, Reichert and Klein wanted to get it out into the world, but they didn’t want to go the traditional route, which was hiring a distributor. That route would mean both losing money and losing control of the film. So they decided to do it themselves. According to Reichert, they learned to operate an offset press and made their own posters to advertise. When the orders rolled in — and they did roll in — the two went to the local post office to send off copies of the 16-mm film. Then they went back to the post office to collect the checks that followed. So many checks came in that the two realized they needed a bank account rather than simply cashing their checks at Weaver’s (now Tom’s) Market.

Still, Reichert and Klein, who had since become a couple, graduated, moved to Dayton and continued doing media work, didn’t think of themselves as professional filmmakers. Rather, they thought of themselves as activists.

“Growing Up Female” did get out into the world, and went on to become a classic in the women’s movement. In 2011 it was selected for the National Film Registry, an arm of the Library of Congress that selects 25 films per year “showcasing the range and diversity of American film heritage,” according to the organization web site.

Their success at film distribution led the couple to launch a new endeavor, a co-operative for the distribution of films by and about women. That co-operative, New Day Films, has grown and thrived for 45 years, now with more than 100 members.

Reichert’s efforts to create new ways to distribute film also contributed to her selection for the IDA honor, Kilmurry said.

“She’s not only telling these stories, but creating new avenues for getting them out into the world,” he said.

Film success

Next, in 1974 the couple made “Methadone: An American Way of Dealing,” about how this country deals with heroin addiction, based on interviews with those involved in a Dayton methadone clinic.

A focus on marginalized people continued in the next two films by Reichert and Klein, “Union Maids” and “Seeing Red: Stories of American Communists.”

Most surprising was the success around “Union Maids,” the true stories of three women involved in the fight to form industrial unions. Reichert and Klein spent only three days in Chicago interviewing and filming the women, doing most of the camera work themselves. The low-budget ($12,500) film was black and white and only 48 minutes long. Still, it earned a review in the New York Times and, amazingly to its creators, a nomination for an Academy Award.

“It was a huge hit in the women’s, socialist and labor movements,” Reichert said. “It was crazy. It must have been the least expensive film ever nominated for an Academy Award.”

That surprising success continued with “Seeing Red,” sparked by the couple’s “Union Maid” contacts and growing awareness of the link between the early labor movement and the American Communist Party. The film took six years to complete, including interviews with 400 people in San Francisco, Chicago and New York. Many were reluctant to speak due to their fears of backlash again Communists, according to Reichert, but the couple gained trust because of their prior work in “Union Maids.” With a $250,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, this film was in color, and there was money enough to hire more help.

Again, to the couple’s surprise, it was nominated for an Academy Award. At about this time, according to Reichert, the couple began calling themselves filmmakers.

And while their films found success, there were the challenges and demands of making a living and a personal life. Reichert and Klein by now had a young daughter, Lela, and were teaching filmmaking full time at Wright State University. While their marriage dissolved a few years later, the two continued team-teaching and working on each other’s films.

Reichert’s work continued with “A Lion in the House,” a 2006 film made with Steven Bognar. The film follows five children with pediatric cancer and their families, along with doctors and nurses at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. It won a Primetime Emmy for Exceptional Merit in Nonfiction Filmmaking in 2007, and was a nominee for Best Feature Documentary in the Independent Spirit awards.

“‘Lion in the House’ is a beautiful and intimate film,” Kopple said.

in 2009, Reichert and Bognar finished “The Last Truck: Closing of a GM Plant,” which follows the lives of factory workers as the company closes their plant. That film was nominated for an Academy Award in Best Documentary Short Subject in 2009. And their work continued in the 18-minute “Sparkle,” about the Dayton Contemporary Dance Company dancer Sheri Williams, and the 2016 “Making Morning Star,” about the Cincinnati Opera and the “joys and challenges of developing a new American opera,” according to a press statement from the Wexner Center for the Arts, which will launch a retrospective of Reichert’s work in 2019.

Current projects include “American Factory,” which was just accepted into the 2019 Sundance Film Festival (see sidebar), and “The 9 to 5 Project,” about an early 1970s movement in Boston among female office workers attempting to force changes in their workplace and conditions.

To Reichert’s daughter, Lela Klein of Dayton, her mother not only shines a spotlight on women’s challenges, but also has lived those challenges and prevailed.

“I’m really proud that my mom is being honored in this way and especially to see her recognized as a leader in her field, a field that was, until recently, utterly dominated by men,” Klein wrote this week. “For her to be a working mom in that community was never easy. My mom has always been really intentional about mentoring and supporting other women and as a consequence, I got to be raised by amazing and creative women. What a blessing.”

As the work continues, Reichert faces a new challenge, that of battling cancer. First diagnosed with lymphoma in 2006, Reichert had treatment and was in remission until about nine months ago, when cancer re-emerged. She’s recently completed another round of chemotherapy and is recovering from that treatment.

“Cancer has had a big impact,” Reichert said this week, regarding her work. She didn’t stop working, and took on as much responsibility as she could.

“There were times I was on conference calls while lying down and getting chemo in the hospital,” she said.

But there were also days she couldn’t work at all, and she gives credit to her team, especially Bognar, for both caring for her and continuing to move the film forward.

“I’m lucky to have an amazing partner, who seems able to carry any load thrown at him,” she said regarding Bognar. “And I couldn’t have done it if I didn’t have such a good team.”

She’s looking forward, this week, to attending the IDA ceremony in Los Angeles, which she and Bognar are fitting in after a trip to Chicago to continue work on the “American Factory” film. The final cut of that film is due soon at Sundance. The work doesn’t stop. And neither do the joys and challenges of being a filmmaker.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.