"Ad Parnassum," Paul Klee, 1932. (Via Wikiart.org)

First Lines — The freedom of poems

- Published: February 28, 2019

There is enormous freedom in a poem. It is the same freedom found within the human mind. Emily Dickinson put it this way:

Some poems concentrate their attention to a single moment. Yet a curious thing happens. Other moments weave in. Words are fluid, multivalent. So are pauses. Images and sounds open to other images and other sounds. No moment, and no poem, is too small to contain “the Sky.” Dickinson’s poems are models of such compression — and expansion. In the smallest possible space, she fits the infinite.

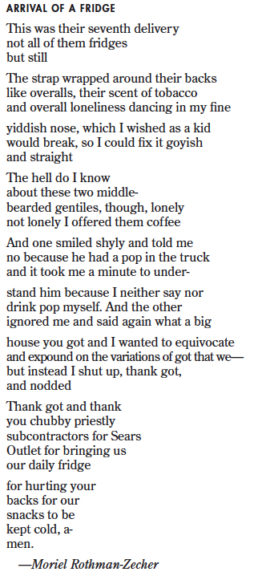

This month I am happy to share a poem by Moriel Rothman-Zecher, a poet, novelist and nonfiction writer. Born in Jerusalem, Mori grew up in Yellow Springs, and returned recently to live in the village with his wife and their young daughter. Mori is the author of the award-winning debut novel “Sadness Is a White Bird,” set within the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. (He confessed in conversation that he “tore to shreds about 10 poems” in the making of that book.) Mori’s poem for the News, “Arrival of a Fridge,” crossed my desk a couple of months ago. I was immediately taken with its fluidity and multiplicity. Also with its mesh of humor and earnestness. A retelling of an apparently simple incident, the poem flows out in several directions. The mundane feels expansive, rich. Here it is:

I like the speaker’s voice: wry, self-deprecating, yet also genuinely vulnerable. The poem walks a line between irony and earnestness. There is something ridiculous about thanking Sears Outlet subcontractors for their service in the form of a poem-turned-prayer, yet I can’t dismiss the poem’s final funneling into the divided “a- / men” as a joke, or mockery. The poem registers an interpersonal unease that is also partly an internal unease. Elements of cultural, socioeconomic and personal distance and dislocation eddy and jostle here. But lightly, playfully.

One of the poem’s pleasures is its language play. That word “pop.” So particular to parts of the Midwest, so quaint and foreign to other ears — “pop” becomes a marker of difference, of missed connection. It’s also a funny-sounding word, and we get to experience the joy of its funny sound. Another bit of semi-serious sonic play spins out from the word “got.” It’s the Yiddish word for “god,” Mori explained when we spoke recently. He keeps it lower-case because “any version of god that can exist in this poem has to be lower-case.” The word gets repeated three times after its original usage. Torqued or tweaked each time, it finally becomes “Thank got,” the start of the poem’s closing “prayer.”

Mori pointed out that poems “allow for very simultaneous reverence and irreverence.” That is exactly the case here. A little snarky and a little holy, his poem asks for a blessing wide enough to hold — like a really big fridge? — the all.

To read other First Lines poetry columns, visit the archive page here.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.