"Sun over the Pine Forest," Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, 1913. (Via Wikiart.org)

First Lines — The magic of small forms

- Published: June 8, 2019

Short poems place unusual demands on the poet and reader. They ask us, poet and reader both, to enter the vast world through a tiny gate. They are a very small ship for exploring a very big universe. But then it turns out that their smallness is actually their magic and strength.

Japanese haiku is the quintessence of small form. Adopted in the West in various ways, haiku turns on a single moment, offering a couple of clear images, usually from nature. Typically written in three lines, haiku is over almost before it’s begun. The form is famously direct, but also — mysterious. A bit misunderstood in the West, haiku embodies a paradox. These poems ground us in order to take us places. And the places haiku takes us are the ones we can only get to from inside this place, and this time.

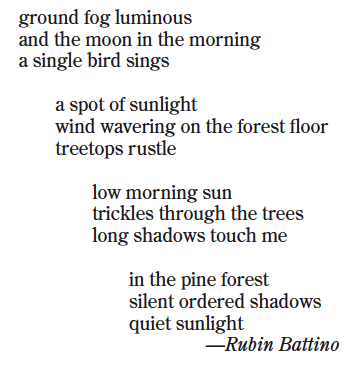

This month’s poems come from longtime villager Rubin Battino, who has been writing three-line poems for decades. “We hit it off,” he said of the short form, his own adaptation of haiku. A writer, mental health counselor and retired professor of chemistry from Wright State, Rubin spent two stints as a visiting professor in Japan, and was introduced to haiku in that country. He enjoys the challenge of “capturing experience in three lines,” he said.

In the seasonal haiku that follow, see if you can enter not just the moment, but the imaginative space the moment opens into.

The first of these, the poem that begins “ground fog luminous,” quickens my interest in what is happening with the fog, with the morning moon. Is the sun shining through fog coming up, or is the moon shining down through fog as it sets? There’s a meeting, a mingling. The “single bird sings” lifts me to a different place. It’s possible that the moon itself is the single bird; it’s also possible to experience the bird as a song in the fog — a single voice issuing from the large and luminous fog that is a little bit sun, a little bit moon.

I also love the poem that ends “long shadows touch me.” I love the intimacy of that line. While haiku is often assumed to be nonpersonal, poet and translator Robert Hass suggests that the form is actually deeply personal, in the sense of having “the flavor … of a particular life.” I feel that here, with the long shadows. The poem is intensely present to the experience of early morning, yet it is courteous, somehow, letting the morning be the morning, and feeling glad just to be touched by shadows.

As a counselor, Rubin practices hypnotherapy in the tradition of psychologist Milton Erickson. He sees similarities between hypnosis and poetry. Both “attempt to speak with the unconscious mind,” and do so through what Rubin calls “the precise use of vague language.” Poetry’s language is “vague” in the sense of being nondidactic, I would suggest. Poems don’t tell you what to think, or even to think. They just — well, think, and let you think and feel along with them.

Haiku, of all poetic forms, is deeply nondidactic. That is one reason why haiku and small poems with a haiku spirit are at once extremely fleeting and, like a struck bell or the song of a single bird, resonant.

*This column originally appeared in the May 16, 2019 issue of the News.

To read other First Lines poetry columns, visit the archive page here.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.