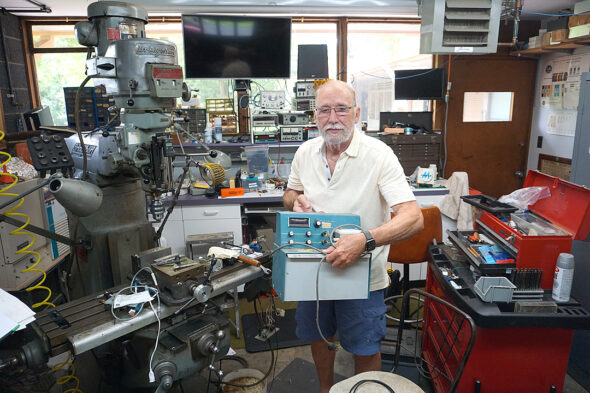

Villager Alan Brunsman, a former longtime employee of Yellow Springs Instruments, or YSI, recently held aloft a revolutionary medical instrument that he and other YSI developers built in the early 1970s: the Model 23A, a device that could measure a patient’s glucose level with an unprecedented 98% accuracy. Although Model 23A was discontinued nearly five years ago, the instrument’s legacy persists. Much of today’s technology that monitors blood sugar relies on the same groundbreaking technology found in 23A. Brunsman is pictured here in his Orton Road workshop. (Photo by Reilly Dixon)

Yellow Springs Instruments— Model 23A’s revolutionary legacy

- Published: August 27, 2021

Keeping track of blood sugar levels can be a matter of life or death for a diabetic.

For the hundreds of millions of people around the world living with diabetes, entire lifestyles and diets are tailored to the demands of the disease — insulin pokes and regular monitoring of glucose levels are just a part of everyday life.

Most diabetics opt to manage their disease at home, usually with the help of commercial blood sugar testing kits. A prick of the finger and a meter will read out your current blood sugar level.

But do these little machines provide diabetics with all the information they need to know? Are they accurate and precise enough with their glucose readings?

These were the questions a team of engineers and developers at Yellow Springs Instruments, or YSI, — now owned by parent company, Xylem — wrestled with back in the late ’60s. This mechanically minded group of local problem solvers set out to build a device that could efficiently record glucose levels with precision unmatched by any of the other devices on the market.

And in less than a decade, they built just that. YSI’s new device could measure glucose within 2% of the targeted range. This was Model 23A.

“It was just beautiful,” said project manager and longtime villager Alan Brunsman in a recent interview. “Model 23A worked exactly as it should have.”

“Even then, we knew how important it was to a diabetic to know exactly what their [blood sugar] level is,” Brunsman said. “You’d like it to be somewhere between 80 and 120 milligrams per deciliter. If it’s below 80, you can die. If it’s above 120, you can get sick, lose toes, et cetera. Sure — diabetics want to know if their levels are trending up or down, but most want to know the exact number; 23A did just that.”

Brunsman, who worked for the vast majority of his career at YSI, sat down with the News recently to tell the long and complicated story of the groundbreaking Model 23A. Although the machine was taken off the market a little over five years ago, Brunsman said that 23A’s profound effects on the field of biosensors can still be seen. Over the course of its nearly 50-year implementation and beyond, Brunsman said, the constituent technology in 23A has likely saved the lives of millions.

Building a biosensor

The story begins, Brunsman told the News, in the basement of Antioch College’s science building, YSI’s first home. The company was founded in 1948 by two local engineers and a chemist, Hardy Trolander, John Benedict and David Jones, who forged their partnership from their time at Antioch College. Their initial work came from Fels, Kettering and Wright-Patterson Field, which brought them measuring and testing equipment to either repair or redesign.

One of YSI’s earlier projects was developing components for one of the first heart-lung machines the world had ever seen. Tasking the developers and researchers at YSI with this project was renowned biochemist and Antioch alumnus Leland Clark, who is widely acknowledged as one of the founding fathers of the field of biosensors.

One of the more significant parts of Clark’s heart-lung machine was the inclusion of a revolutionary membrane electrode, a sensor that measured oxygen — the first of its kind. The electrode was made by placing polarized platinum and silver wire electrodes behind an oxygen membrane. The electrodes catalyze a chemical reaction, and then issue out a measurement of ambient oxygen concentration in a given liquid.

Here are several Clark Electrodes, named after Antioch College alumnus and world renowned biochemist Leland Clark. Clark Electrodes played an instrumental role in powering Model 23A. Derivative technology is still used in many commercial glucose measuring devices on the market today. (Photo by Reilly Dixon)

“It’s simple enough,” Brunsman said with a smirk, “But still really, really inventive for the time.”

And it was. In 1962, the burgeoning field of biosensors kicked off with the patenting of the oxygen sensor bearing its inventor’s name: the Clark Electrode. This device ushered in a new era of clinically measuring oxygen levels that expanded far beyond its initial use in the heart-lung machine — especially at YSI.

Fast forward to the end of the decade when Trolander, then CEO of YSI, and Ed Molloy, then manager of a new products department, brought Brunsman into the project fresh out of college.

Right away, Brunsman was assigned the role of projects manager. Over the coming two years, until the end of the ’60s, he worked on redesigning an impressive array of different instruments: temperature controllers, drive-in window amplifiers, connectivity meters and others — but never a clinical electro-chemical instrument.

“The first two years [at YSI] were a real education on how taking a design from concept worked,” Brunsman said. “YSI was a really unusual place at that time. It was full of very, very interesting people. And they were all — myself included — generalists. That means if someone came to us needing something designed, whether it was a mechanical, electrical or a chemical problem, it didn’t matter. We’d work on it together.”

Given the growing preoccupation with biosenors, Brunsman and his colleagues were beginning to wrestle with new and pressing challenges.

Could YSI create a device that accurately measured glucose? Could Clark’s electrode sensor be developed into a commercial instrument?

Upon Molloy’s untimely death in 1969, Brusnman was tapped to lead the charge in answering those questions. Clark had tasked Brunsman and his team at YSI to measure glucose under certain parameters: a device would have to accommodate a small sample size, provide results in less than a minute and work on whole blood.

“They said, ‘Here, Alan, do this project,’” Brunsman said. “Everytime I think back on it, I think, ‘What the hell were they thinking?’ I was two years out of college. Never done a clinical instrument. No degree in chemistry. It was me standing there alone.”

But in reality, Brunsman was far from alone. YSI immediately hired two additional members of the project team: David Newman, an engineer with Antioch roots, and Jeff Huntington, a local chemist with a Ph.D. Additionally, at the time, YSI was in the midst of forging a relationship with the Danish multinational healthcare technology company, Radiometer. Drawing from the work of the

Radiometer researchers and developers in Copenhagen and the team in Yellow Springs, Brunsman, Huntington and Newman oversaw the two-year development of a new device that measured glucose like no other product available for clinical use at the time. This was the Model 23.

In the summer of 1973, Gert Kokholm, at right, of the Danish biomedical development company Radiometer came to the village to visit YSI. At left is Hardy Trolander, the then CEO of YSI, and in the middle, Alan Brunsman. This international meeting occurred in the era when Brunsman and his colleagues were developing the Model 23A, a revolutionary device that measured glucose levels. Radiometer provided David Newman, one of Brunsman’s contemporaries, with the technological inspiration for the membrane-electrode mechanism in 23A that allowed for the device’s unparalleled accuracy. (YS News archive photo)

From 23 to 23A

The first glucose instrument, Model 23 followed Clark’s original concept. Here’s how it worked: there’d be two electrodes — one measured glucose and interferences, while the other measured just the interferences. A user inputs a blood sample that interacts with both Clark electrodes — one would be coated with a glucose oxidase enzyme, which would catalyze glucose to hydrogen peroxide. The other electrode would be bare. One electrode signal is subtracted from the other. The difference should be the glucose level.

But there was a problem.

“We discovered after a while that the instrument gave a different response for every interference,” Brunsman said. “So, it didn’t really work as we wanted it to.”

As Brunsman explained, the problem came from interferences such as ibuprofen or ascorbic acid. These “interferences,” as Brunsman described them, would lead to different glucose readings.

In short, Model 23 wasn’t as accurate as Brunsman, Newman and Huntington had hoped.

“We sold some [Model 23s], but ended up taking them back,” Brunsman said. “We recalled them off the market immediately when that defect was detected.”

“It was back to the drawing board,” he said.

The team regrouped and re-evaluated their designs. Despite the project’s shortcomings, Trolander and other YSI leaders maintained their faith in the team’s ability to solve the problem.

“Sometime in 1972, we rallied the troops and went out to Copenhagen to discuss where we were,” Brunsman said. “The engineers over there were also running into our problem.”

While abroad, Brunsman, Newman and Huntington happened across the work being done by one particular Radiometer researcher.

“This guy had taken a salinization membrane and put it over an electrode to measure something other than glucose,” Brunsman said. “Salinization membranes are used in machines that can make salt water potable. It’s a very selective membrane that doesn’t allow everything through. It gets rid of interferences.”

Brunsman and his team were captivated by this breakthrough — Newman, in particular. Whereas YSI’s glucose measurement devices kept butting up against unexpected interferences, their Danish counterparts inadvertently cracked the code.

“When we returned home, we ordered some salinization membranes right away,” Brunsman said. “And David [Newman] developed a new membrane based off the properties that Radiometer had developed. He made them much, much thinner. His membranes captured all of the interferences we had been experiencing.”

Suddenly it worked. Their device worked.

“It was beautiful,” Brunsman said. “Just beautiful.”

With the new membranes hooked up to Clark’s electrodes, every interference with Model 23’s glucose readings was negated. Suddenly, Brunsman and the rest of his team at YSI were getting consistently accurate measurements on their blood samples. This new development could quantify blood sugar levels with 98% accuracy — higher than most devices on the market today, Brunsman said.

The name of this new device? Model 23A: the then-proclaimed pinnacle of glucose measurement devices.

According to Brunsman, it took him, Newman, Huntington and the rest of the team at YSI only two years to reconfigure the error-prone Model 23 into the accurate 23A. It was available on the commercial market for clinical use by 1974.

“We worked so cohesively as a team,” Brunsman said with a grin. “I had worked on ventures before, and I’ve worked on ventures since. And those can take 5 to 10 years. To turn around something like the 23 to the 23A in just two years — even with all of us making all the electronics, hardware, chemistry, the standards — just everything. It was just incredible.”

“We just did things quickly back then. That was just the culture at YSI,” he added.

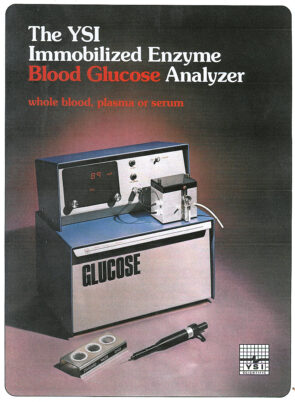

This is Model 23A as it appeared when it went on the clinical market in the mid-1970s. YSI’s derivative devices that would measure biochemicals other than glucose looked similar. (Submitted photo)

A lasting legacy

Beyond its immediate commercial success, Model 23A represented a major milestone in the field of biosensors — and in particular, the development of such machines. According to Brunsman, the mid-’70s was a time when developers, engineers, scientists and programmers — in both the private and public spheres — were making massive technological advances on a regular basis.

“It was a remarkably inventive time,” Brunsman said.

What set YSI apart from many of its contemporaries and competitors wasn’t a thirst for capital gain, but instead a desire to contribute to the greater good.

“I remember Hardy [Trolander] telling Radiometer, ‘I don’t want to hold onto this machine and have complete control of it. It could be really important for the world.’ He thought there should be more than just one person inventing and perfecting it,” Brunsman said.

“The whole philosophy undergirding the development of the machine was that by working together, the engineers could collectively get it to run faster and more effectively.”

Brunsman said that Trolander didn’t believe in patenting everything he could, only the wholly unique devices — an attitude quite unusual for a CEO of a scientific instrument company.

“He did patent [Newman’s] salinization membrane device, but that’s it,” Brunsman said. “That was unique enough for Hardy. But there isn’t another patent on the glucose machine. And I could go through all of the components and come up with at least 10 other parts that very easily could have been patented.”

This open-ended approach to machine-making soon paid off again for YSI. Not long after 23A hit the market, Leland Clark again approached Brunsman and the other developers at YSI and pointed out that their methods for measuring glucose could be easily retooled to measure lactic acid.

“You know — the stuff your body produces when you run out of oxygen,” explained Brunsman.

“Lactic acid is a metabolic product. When you run out of it, then you know you’re not getting your blood as oxidized as it should be.”

It turned out, Clark was right. In no time at all, using the same technology — from the membrane-to-electrode interaction, the interference compensation, all the way to the classic exterior blue box — YSI was able to produce a lactic acid measurement instrument. And some big-time consumers took notice.

“Leading up to the 1984 Olympics, we got pressed by the U.S. Olympic team who wanted to measure their athletes’ lactic acid levels,” said Brunsman. “YSI had the only instrument that’d do it. So we did it, and they integrated the lactic acid instrument we developed into their training regimens.”

Whether it actually helped them is another story, Brunsman said.

“Just because you can measure something in your body, doesn’t necessarily mean you should train to that number.”

But years later, before the 1988 Olympics, the Chinese Olympic team “bought up as many of these instruments as they could,” Brunsman said. “And sure enough, the Chinese swimming team really came into their own that year. I’d bet anything that it was because of our lactic acid instruments.”

Over the years, YSI would go on to retool 23A to measure a wide array of biochemicals beyond glucose and lactic acid. Through minor adaptive technologies, derivative machines of 23A could measure ammonium, cholesterol, ethanol, galactose, glutamine, glutamate, glycerol, lactose, methanol, potassium, starch, sucrose, xylose and more.

“It was always the same box, just a different membrane churning out different numbers. Same blood sampling methods,” said Brunsman. “23A really changed everything.”

“And if you look at how people measure glucose today, they’re typically using some modification of the electrode system that Leland Clark had initially developed and that we furthered,” Brunsman said. “Even the stick ones — it’s using an electrode and glucose oxidase to measure the glucose in your blood. Derivative designs are still used to this day all over the world.”

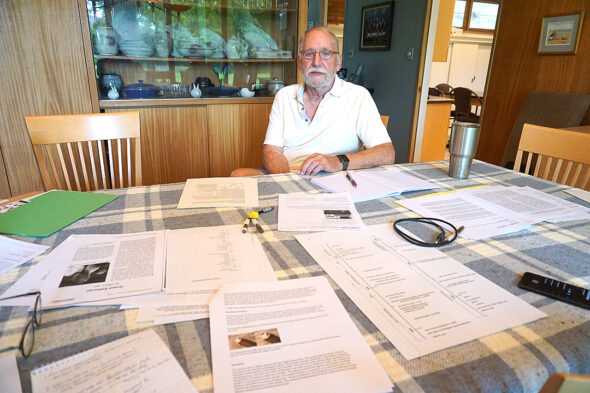

Alan Brunsman in his home. In front of him is a collection of documents he’s amassed over the course of his life that detail the significance of his and other’s work at YSI — on Model 23A and other significant biosensor instruments. (Photo by Reilly Dixon)

23A and beyond; YSI and Xylem today

Nowadays, Model 23A is no more. Only its legacy remains.

Around 1989, its successor, Model 2300 STAT came on the scene. The 2300 STAT measured both glucose and lactate. It had a microprocessor and a more automated interface that made the machine more user friendly. Then, what followed was the 2300 STAT+, a more refined version of its predecessor.

But in 2016, Xylem, now the parent company of YSI, opted to discontinue the device. The current head of product development at Xylem, Chris Werner, in a recent interview, cited a diminishing demand from clinicians and “prohibitive” FDA regulations on biosensors that led Xylem to stop manufacturing 2300 STAT+s and similar machines.

There are, however, still many 2300 STAT+s in use around the world, said Werner. YSI still provides replacement parts and services to those machines when needed.

This discontinuation coincided with the shift in technological focus at YSI when Xylem — formerly ITT Corp. — purchased the company in 2011. Whereas YSI was previously interested in developing and manufacturing medical instruments and biochemical analysis devices, Xylem ushered in an era centered around water quality testing devices.

“But life sciences continues to be in the background at Xylem,” said Werner.

Brunsman added that one of the fatal shortcomings of Model 23A and its successors was that the machines never went commercial — they were only for clinical use. This, as Brunsman saw it, was the result of a certain sect of physicians never seeing the importance in their patients knowing the precise number of their glucose levels. Instead, as these physicians saw it, patients only need to know a general trend — whether their blood sugar levels are rising or dropping.

“By and large, doctors seem to be satisfied with the finger stick and the little take-home strips people can do on themselves,” Brunsman said. “They thought that’s enough information for their patients. Any more data, and patients might get overwhelmed with the information an instrument is providing them. To my knowledge, doctors still believe this now.”

Brunsman sees things differently. He believes knowing a precise number could potentially save lives — especially as the number of people living with diabetes continues to rise.

“One time I was in the hospital and my blood pressure had dropped. By the time [doctors] had given me medication for it, my pressure had returned to normal. So there I am — blood pressure then going through the ceiling. I thought my head was going to come off. Their timing was just terrible. You need to know what your blood sugar is right then and there. Our machine was designed to do just that.”

These days, Brunsman is still living in the village with his wife, Becky. Although he retired from YSI in 1996, he remains focused on hashing out some of the complexities he and his team at YSI encountered in their projects.

More recently, on his own time, Brunsman and some partners have been brainstorming ways modern technology could be integrated with the mechanics of the Clark electrode system — particularly by building an implant that could provide a user with consistent and accurate glucose readings. He remains deeply troubled by all the physicians and patients who are content with having a vague notion of blood sugar levels; he still preaches the need for absolute accuracy.

Brunsman is still riding the momentum that was generated at YSI, right at the outset of his career in the early ‘70s. He recalls the spirit of innovation and ambition among his fellow instrumentalists, and tries to harness that same energy in pushing the boundaries of what can be measured and to what greater degrees of accuracy.

In a perfect world, Brunsman said, every diabetic would have their own personal glucose measurement device, like Model 23A — one that didn’t cause pain or discomfort — that would reconnect users to their bodies, not paint a vague picture of what might be going on under the surface.

“It’d be fantastic,” he said. “It’d save so many lives.”

One Response to “Yellow Springs Instruments— Model 23A’s revolutionary legacy”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

As a type 1 diabetic and former YSI employee. I really enjoyed reading this article. Thank you for your work.