Pictured here is Xenia Avenue in the early 1940s. Taken from the top of the building that is now Tom’s Market, looking North, this photo foregrounds two important buildings in Yellow Springs’ history: the building that currently houses Emporium Wines & Underdog Cafe, and the original building that’s now the back half of the Senior Center. (Photo courtesy of YS Historical Society)

The architecture of a village

- Published: March 10, 2022

The following article appeared in the 2020–21 Guide to Yellow Springs: Downtown, Then and Now. Click here to read more articles from that year’s guide.

Like many things in the village, the architecture within the central business district of downtown Yellow Springs is, well, unusual.

The edifices that line the central throughways in the heart of the village form a patchwork of design and structure. The structures are quirky, asymmetrical and kaleidoscopic in color — the squat skyline, seldom rising above two stories, is jagged and sundry.

But downtown’s buildings do more than display the stylistic sensibilities of yesteryear — they tell the story of Yellow Springs. Indeed, much of the village’s long history can be found in its architecture, hidden in plain sight.

Downtown Yellow Springs’ architectural significance was set in stone — so to speak — in 1982, when the downtown and surrounding area earned a listing in the National Register of Historic Places. The official historical designation was granted “both because of its place in the area’s history and because of its historic architecture,” according to the entry in the register.

Yellow Springs was a “valuable addition” to the register, said David Simmons of the Ohio Historic Preservation Office back in 1982, because of “the sense of time and place” that is “so pervasive” in the village. Owing to the older structures that have been preserved, Yellow Springs is “in a sense a 19th-century community,” said Simmons. Nearly 40 years later, this remains true. The construction of many of the downtown buildings dates back to over a century-and-a-half ago, with some newer additions to the streetscape.

Built beginnings

The middle decades of the 19th century were a pivotal time in the history of Yellow Springs. Until the 1840s, Yellow Springs was a rustic settlement squarely on the edge of the Western frontier. It was composed of a church and a couple of homes — one of which is now known as Ye Olde Trail Tavern, the back part of which, according to some sources, was built in 1827; other sources suggest 1840s. Eventually, though, the mineral spring in Glen Helen began to attract more visitors and, as a result, more settlers.

This was around the time when Judge William Mills, largely considered to be the founding father of the village, convinced railroad developers to build the line through Yellow Springs, rather than Clifton, by agreeing to raise money for it. By 1846, the Little Miami Railroad opened up and ran right through what would become downtown. Once the railway was fully operational, three trains would complete a daily circuit from Cincinnati to Springfield.

With this railway came a surge of business; frontier entrepreneurs scrambled to get a slice of the pie that Mills had set out for them. By the end of the decade, merchants, grocers and shopkeepers set up shop in what is now the Dayton Street portion of the business district.

An entry in villager Cosmelia Hirst’s 1895 scrapbook says the following of that era: “When the word went out that the Little Miami Railroad would pass this point it was the signal that here would be a place for business, hence the rapid building of the town. In all directions from early morning until late evening was heard the sound of saw and hammer. Every man was busy fitting up a place for his own special industry and in making a home for his family or assisting others to do it.”

Before the end of the century, many of the buildings that comprise the downtown commercial district would be built, and aside from a few exceptions and minor aesthetic changes, many of them remain much the same today. By and large, these buildings reflect the design preoccupations of the 19th century.

As historian and expert on local architecture Kevin Rose put it, the builders of the downtown structures, “some of whom were surely from the east,” likely brought their design concepts west when they settled in Yellow Springs.

As a result, we can see four primary architectural styles in full flush in downtown Yellow Springs: Greek Revival, Federal, Victorian Italianate and vernacular.

Greek Revival style

According to Rose, who currently works as an historian and director of revitalization for the Springfield-based Turner Foundation, and who has occasionally led architectural tours around Yellow Springs and the surrounding area, the majority of buildings constructed in the village’s early years were designed in the Greek Revival style.

But, he says, the downtown buildings vary from the style’s occasional grandiose elements. They could “perhaps be more accurately described as ‘low-style’ Greek Revival,” said Rose. The buildings, he explained, have no large columns, minimal or no decorative panels and no large Greek entryways, although the latter two could have been removed over time.

“The structures are simple in their expression of the Greek Revival style: bricks extended to mimic pilasters and simple six-over-six windows — very common for this period, as large sheets of glass were not easily made,” he said.

Rose added that particular kinds of cornices — decorative molded projection at the top of a wall, window or construction — are also common within the Greek Revival tradition.

Among one of the earliest Greek Revival structures to appear downtown is the building that now houses the Emporium Wines & The Underdog Cafe and the apartments that sit above. Tax records reveal that this structure was in existence in 1854, and it is shown on one of the village’s earliest maps in 1855.

It has tall, green brick pilasters on each side of a center entrance to the upstairs apartments.

There is a cornice over each storefront and large windows on the front facade with flat soldier arches.

“Although garishly painted and altered somewhat,” reads a cheeky entry in the Ohio Historic Inventory, or OHI, from 1979, “its historic origins are obvious and it lends an aura of the past to the streetscape.”

Another downtown structure that embodies the Greek Revival style, perhaps more prominently than the Emporium, is the tall apartment building at 139 Dayton St., across the street from the laundromat and next door to the Corner Cone.

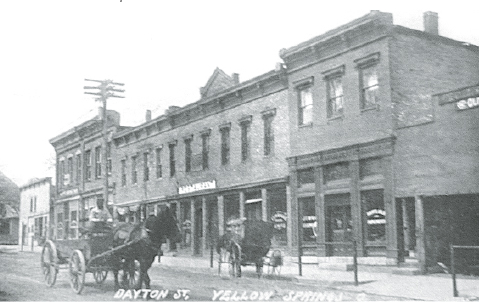

The building was built sometime in the 1850s or ’60s and was a part of the early streetscene of Yellow Springs. The portion of Dayton Street where the building rests was the earliest developed part of the village.

The Greek Revivalist elements of this building are perhaps most visible in the two-story, square pillars that protrude from the indented double gallery porch. The top of the building features cornices that jut inwards and a pedimented gable. The OHI entry for this building, again written in 1979, states that the building, which was then surrounded by a used car lot and other businesses, was “modernized within an inch of its life,” but that “its original dignity shines through.”

241 Xenia Ave., in 1973, when it contained a beauty shop, drug store and bicycle shop. It exemplifies the Federal architecture style. The stately brickwork, rigid geometry, joined chimneys and symmetry in its overall appearance all suggest a 19th-century aesthetic. (Photo courtesy of Antiochiana, Antioch College)

Federal style

Like Greek Revivalism, Federal-style architecture had a firm aesthetic foothold in the U.S. throughout the late 18th- and mid-19th centuries. Having evolved from the Georgian style of architecture, the Federal style is characterized by relatively simple modes of geometric expression. Federal buildings are typically two stories high, two rooms deep and adorned with plain columns and moldings.

According to Rose, there is some difficulty in making the distinction between the Federal and Greek Revival styles in the village’s downtown buildings. This, he said, is simply because architectural styles evolve over time — they diverge, combine and change in often subtle ways, thereby making definitive classification anything but easy.

“In some ways the Federal became the Greek Revival,” said Rose. “The massing and shape of the Federal Houses in Ohio in the 1830s and 1840s incorporated elements of the Greek Revival Style in the 1850s and early 1860s.”

Take, for instance, the Senior Center, whose original two-story brick structure was built in 1862, according to tax records.

“At quick glance, the Senior Center looks Federal,” said Rose, “but the inclusion of cornice returns on the sides and lack of other Federal elements makes it difficult to make the latter classification.”

Perhaps the most attractive architectural feature of the original brick structure of the Senior Center is the joined chimneys at both ends of the building — both of which are complemented by the cornices and relatively simple decorative panels, or friezes. At the front of the building is a modern-seeming one-story brick addition that is capped by a low-pitched triangular gable. The red bricks of the addition provide significant contrast against the stark white paint of the original two-story building.

“Even the modern front addition cannot hide the dignity of this old Federal,” states the OHI report on the building. “It adds a bit of nineteenth-century ‘skyline’ to downtown Yellow Springs.”

Another classic Federal-style building downtown is 241 Xenia Ave., which, until recently, housed the Blue Hairon Salon and Wander & Wonder. Built in 1857, this building, like the Senior Center, features joined chimneys at each end of the building. It has cornices that jut inwards and ornate, decorative panels. After its initial construction, a porch with a shed roof and square columns was added.

Victorian Italianate buildings on Dayton Street as they appeared circa 1905. Visible are the decorated cornices and ornate friezes that distinguish the first floor from the second; most feature decorated columns. At right, the building that now houses AC Service was the only one to survive the 1895 fire. (Photo courtesy of Antiochiana, Antioch College)

Victorian Italianate style

There are only a handful of buildings in Yellow Springs’ central business district that could be described as Victorian Italianate. This style came about in the mid-19th century as part of a larger Romantic movement in the arts. These buildings are commonly recognized by their tall, narrow windows and their low-pitched or flat roofs with ornate, overhanging eaves.

A block of connected buildings adorned with this style graces Dayton Street. One segment of this block consists of the Dayton Street Gulch and Lucky Dragon, with YS INK Arts Collective and some apartments upstairs. This section of the block was likely built just after the 1895 fire. Both the entrances to the Gulch and the Lucky Dragon sit between projecting pilasters — which, owing to the contrasting paint job, almost give the illusion that these faux columns are holding up the second story.

True to the Italianate form, this building features tall windows on the second story, with each street-facing window having an ornate crown. Overhanging the apartments and YS INK above the Gulch is a decorative cornice that matches the color scheme of the Gulch below. The white molding and brackets of the cornice provide the green and orange panels with a fine border. While this cornice seems to harken back to the 19th century, it was actually added sometime in the mid-20th century.

The adjoining portion of the block consists of the Import House, the Spirited Goat Coffee House and more upstairs apartments.. Again, this structure exhibits a Victorian Italianate style with features similar to its next door neighbor. A 1979 OHI entry regarding the structures states that these two buildings haven’t changed much over the years. But at the time of the entry, the buildings were “decaying and many [storefronts] are empty.” The author of the entry pleads for preservation and eventual restoration. By and large, she got her wish.

Farther south on Xenia Avenue is another Victorian Italianate building — the structure which houses the Sunrise Cafe. Again, the front is incised with metal pilasters and displays tall, narrow windows. And, like the other Italianate structures in town, this building features an ornamented cornice that overhangs the front facade.

Representing the vernacular architectural style displaying the classic six-over-six window panes are the buildings currently housing the hardware store and Yellow Springs Toy Company. Built around 1853, these are among the oldest buildings downtown. This photo was taken in 1975. (Photo courtesy of the Dayton Daily News)

Vernacular style

Vernacular architecture is perhaps the most idiosyncratic of the styles. It may be described as the miscellaneous architectural category because of how varied each vernacular structure can be.

Builders of these kinds of structures rely on region-specific building materials and design elements, drawing from the resources that are most immediately available. As a result, each vernacular building can look wholly unique, and in some cases, can be a blending of several different architectural styles. Many, if not most, of the buildings in the downtown area have a vernacular character.

One of the tallest buildings downtown is the three-story brick structure that houses Yellow Springs Hardware, built around 1853, is a quintessential example of local vernacular architecture, owing to its unusual shape. Unlike nearly every other downtown structure, it’s not square! It was built with oblique angles to fit the corner lot at the Short Street/Dayton Street intersection.

“I love the way they were built,” said Rose. “They look square to the street, but they aren’t — which can mess with your mind when you walk past them on the sidewalk.”

Rose went on to say that the exterior of the hardware store and the above apartments still exhibit many of the features that were included in their initial construction.

“The building has some of its original six-over-six windows and how you can still see the original openings that were [later] bricked in along Short Street,” he said.

Interestingly, the dynamic geometry of the building might have lent itself to the wide array of businesses it has accommodated over its 150-year-long existence. According to a 2005 Dayton Daily News article on the building, it once housed a college bookstore, an art studio, the area’s first library and hotel, which, at one point, may have had some connection with the abolitionist movement in the 19th century.

Around 1964, the late Alan Macbeth, pictured above in 1984, purchased the building that would become the Oten Gallery. Over the next 50 years, Macbeth adorned the property with his unique approach to brickwork and masonry. The original 1855 structure was a part of the Greek Revival tradition, and was destroyed by a fire in 2000. (From the YS News archives)

All the rest

Suffice it to say, there are countless exceptions to the styles described above. After all, the Historic District encompasses more than just the businesses along Dayton Street and Xenia Avenue — it bleeds into the surrounding neighborhoods as well.

Beyond the central business district, there are two noteworthy structures that represent Second Empire architecture: the imposing Fess House at 830 Xenia Ave. and the Union Schoolhouse, which formerly housed the Village offices, on Dayton Street. Nowadays, those offices are located in the John Bryan Community Center, which itself is wholly unique. Built in 1928 as Bryan High School, the Bryan Center is a gleaming example of Spanish Colonial Revivalism. There’s the Gothic Revivalism of the First Presbyterian Church, which was designed around 1859 by the famous Cincinnati architect James McLaughlin. The Wellness Center at Antioch College is a prime example of Georgian architecture.

Then there are those structures that defy classification altogether. To wit: the Oten Gallery/Smoking Octopus building, with its intricate brickwork, curving archways, unexpected openings and winding walkways. The one-of-a-kind character of this building was the lifework of villager Alan Macbeth, who continued to add to the initial structure — which had been built around 1855 in the Greek Revival style — until his death in 2017.

There are no two buildings in downtown Yellow Springs exactly alike. While some building styles are recognizable, the village is as eclectic as they come. Much like the villagers themselves, the architectural stylings of Yellow Springs have a unique flamboyance and vivacity that is hard to find anywhere else.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.