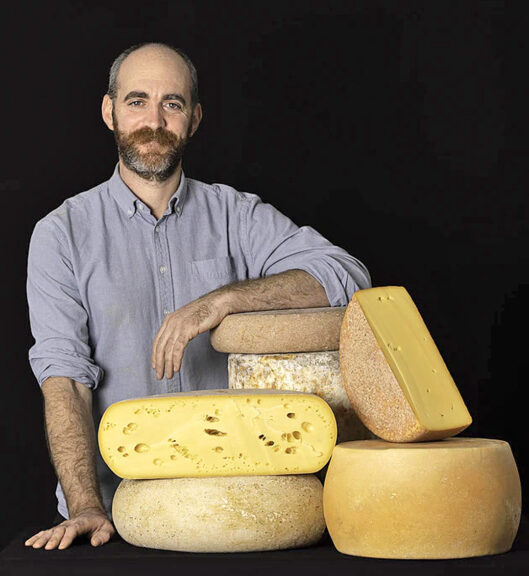

Canadian natural cheesemaker David Asher will lead 20 participants, including several villagers, on a cheesemaking journey at Heartbeat Learning Gardens, beginning Sept. 7. (Submitted photo)

Natural cheesemaking set at Heartbeat Gardens

- Published: September 6, 2022

Villagers may recognize Sandy King, a self-described lifelong local, and her horse Daisy, from the carriage jaunts around downtown they take folks on during the winter holiday season.

But King is also an advanced herbalist and strong advocate of cooking foods using traditional processes for improved health and nutrition — particularly through fermentation processes, which include natural cheesemaking.

This month, King will showcase that interest through a workshop she organized in partnership with Heartbeat Learning Gardens.

The workshop will bring internationally recognized Canadian cheesemaker David Asher to the area for a five-day workshop at Heartbeat from Sept. 7 to 11. Around 20 participants from the village, region and around the country will gather to learn about cheesemaking through natural fermentation taught by Asher. According to King, four slots are also designated for scholarships.

In a recent email to the News, Asher said his family’s farm is just across Lake Erie in southwestern Ontario. The workshop, he said, will be his first foray into Ohio, or the Midwest. Asher described the origins of his passion for cheesemaking, and subsequent quest towards learning more about the process, despite a lack of information via print or online.

“My passion for cheesemaking comes from two angles — one from my love of natural farming, and the other, from my admiration for fermentation,” he wrote. “I started out making cheese over 15 years ago, when I was cutting my teeth as an organic farmer. When I first had access to raw milk from my neighbors’ goats, I was inspired to make traditional cheeses with it.”

According to Asher, he then ventured into other areas of fermenting foods.

“I fermented my milk much like I did my sourdough bread, or my natural wine, by pitching in a natural starter culture, kefir. Encouraged by the success of my first batches, and the lack of information in print or online about natural cheesemaking, I forged my own path towards understanding this truly miraculous food!” he wrote.

“David is going to be teaching an introductory cheesemaking workshop that is going to cover all types of cheese but on a beginner level. He’ll be teaching a type of blue cheese, he’ll be teaching how to make the culture, how to make kefir properly, how to make clabber — a lot of people don’t know what that word is,” King said in a recent interview with the News.

And what is clabber?

“If you remember the old nursery rhyme, ‘little Miss Muffet sat on her tuffet eating her curds and whey’ … the curds are what happens when you put raw milk out on the countertop for two or three days — it coagulates. Even in our own baby’s stomach, if a baby is drinking their mother’s breast milk, if they burp, what ends up on your shoulder is cheese. It’s little curds,” she said.

“This is something David always says — milk’s destiny is cheese,” King said.

The five-day workshop will require 22 gallons of milk, including five gallons of goat’s milk. The milk will be provided by the Amish farmers in Hillsboro, where King is part of a herd share.

“You own a part of the cow and with that share, the farmer can provide you your share [milk] of the ownership of that cow,” she said.

According to King, fresh cheeses don’t last as long and are meant to be eaten right away, depending on the type of cheese. Some take longer to cure.

“When you get to a lactic cheese like a brie it takes two months, and cheddar takes six months or longer,” she said.

King said natural cheesemaking takes time.

“You might be working with a cheese for six hours but you’re not going to be constantly working with it. You’re going to put it out, be gone for an hour, put a timer on it and come back and check if it split — when you put your finger through it, does it split nice and clean or is it kind of falling all over the place?” she said.

King said one of the workshop days will involve making mozzarella cheese in a day-long process.

The cheese will then be the key ingredient of a group pizza that participants will share as an evening meal. According to King, making cheese through a traditional process involves using the senses and asking a lot of questions because in the past, people didn’t have access to modern cooking technologies like temperature gauges.

“You gotta eyeball it. What is the temperature? How does it feel? What does it look like? What does it smell like? Is it stretching?” King said.

King sees the need to return to more natural forms of food production as a central concern of hers. According to King, cheesemaking is a tradition that has been lost to a lot of people.

“It’s important to know that ‘natural’ means raw milk, straight from the cow, warm from the teat — that’s exactly what you need for cheesemaking, warm from the teat, never refrigerated,” she said.

According to Asher, most commercial and home cheesemakers “pasteurize their milk, and then add freeze dried starter cultures from overseas. This includes most raw cheesemakers.”

“My approach differs, as I encourage cheesemakers to keep their own starters, like kefir or clabber, which function much like a sourdough starter, but in milk. These traditional cultures provide all the microorganisms that nearly any cheese needs, and enable cheesemakers to make a cheese that’s tastier, and more ethically and sustainably made, and surprisingly, safer, because of the effectiveness of natural fermentation, compared to frozen starters,” he wrote.

King got involved with cheesemaking as part of a cooking journey that began when she became an herbalist and started attending women’s herbal conferences.

“People say again and again, ‘Hippocrates said, ‘Let your food be your medicine and your medicine food,’” she said.

A vegetarian for most of her life, King said her relationship with food changed, in part, when she started having health problems that were resolved by a diet shift towards fermented foods, including cheese.

“Nutrient density is really important, and a lot of people are having problems with their immune systems. … Society is getting sicker and sicker. When we go back to our traditional fermentation — that’s what making cheese is, it’s a fermentation process called culturing. What we’ve really lost is literally our culture. We’ve been homogenized,” King said.

It was through her food evolution that she first became aware of Asher, meeting him through a cooking course.

“We remained in touch, and we tried for ages to make a class work in Yellow Springs,” Asher wrote. “Thanks to her persistence, and her desire to bring my lessons to the Ohio farming community, we finally were able to make a class work this year.”

According to King, fermentation processes and traditions span the globe and Asher’s next stop after the workshop at Heartbeat is the Netherlands.

“Asher goes all over the globe — Spain, Italy, Colombia and Mexico. He’s been to Africa. He’s got a new book coming out working with an African fermented milk beverage called amasi [a popular drink in South Africa and Lesotho]. It is fermented in a gourd,” King said.

Asher wrote that he and his family have been “on a permanent cheese tour for the past seven years,” and that he’s involved with “teaching natural cheesemaking practices, and encouraging the raw milk movement all around the world.”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.