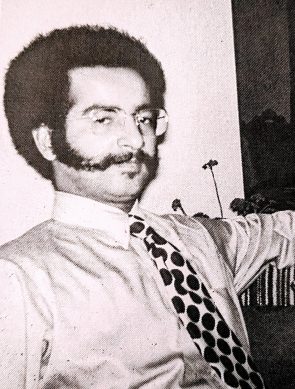

A young John E. Fleming poses on the porch of a home in Legon, Ghana, in Africa. Fleming visited Ghana while serving as a Peace Corps volunteer in Malawi for two years — an experience he detailed in his memoir, “Mission to Malawi.” (Submitted photo)

‘Mission to Malawi’ memoir recalls Peace Corps, Black experience

- Published: December 12, 2024

Local resident Dr. John E. Fleming has spent much of his life working to bring visibility to American history — in particular, African American history — via his five decades as a historian who has helped establish museums throughout the U.S.

Now, after retiring from his most recent position as director of the National Museum of African American Music, Fleming’s focus has turned inward to his own personal history; his memoir, “Mission to Malawi,” was published this spring.

The book details Fleming’s service in the early years of the Peace Corps — during which he was the only Black American in his cohort — against the backdrop of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement. It also provides a snapshot of Malawi, an African nation that, at the time of Fleming’s service there, was newly independent, but still influenced heavily by colonial rule and racism.

Weaving together those two concurrent histories from Fleming’s point of view, “Mission to Malawi” serves as the remembrance of a young man’s deepening understanding of the need for social change through a global lens, and how it ultimately affected the course of his life.

Fleming spoke with the News recently about writing the memoir, which spans the years 1967 to 1969. With the events depicted in “Mission to Malawi” having taken place nearly 60 years ago, Fleming acknowledged that the book’s completion would have been more difficult had he not been a prolific letter-writer during those years. As he explains in the book’s preface: “I was a voracious writer because I wanted my family and friends to write to me, as it was my only form of communication.”

Likewise, he said he was lucky that those to whom he wrote then — including his mother, and future wife, Barbara Fleming —were diligent at saving his letters.

Likewise, he said he was lucky that those to whom he wrote then — including his mother, and future wife, Barbara Fleming —were diligent at saving his letters.

“It’s really sort of funny; as a historian, you’d think you’d remember historical facts as they happened — and it turned out that wasn’t exactly true,” he said.

Fleming wrote the first draft of the memoir without the aid of letters, and later, organized the letters chronologically and read them. The letters allowed him to revise his first draft and improve upon his memory.

“I was very fortunate to be able to find those letters. … The first draft is quite different from what the final manuscript turned out to be,” he said.

Though he said the letters he’d written in his youth didn’t deviate wildly from his own memory, they did contain vital insight into what he felt from day to day, as well as his perspective on his experiences then compared to his perspective now.

In particular, he pointed to his time at Berea College in Kentucky, where he studied before joining the Peace Corps. As Fleming’s book describes, Berea had initially been an integrated college, but was segregated in 1904 by state law until 1954. Fleming came to the college as one of only a few Black students in 1962; by the time he graduated, Berea was still struggling to “find its place in this new desegregated society,” he wrote.

“My experience [at Berea] was, at best, neutral, and at worst, negative,” Fleming told the News. “But I’ve been on the board at Berea now for almost 18 years, and my perspective has changed dramatically. I think that influenced the way I wrote about being a student at Berea, and it turned out a lot more positive than I would have anticipated.”

In the same vein, Fleming’s memoir goes on to detail his Peace Corps training in Alabama and in England as an agricultural volunteer to Malawi. Fleming writes that he learned he was nearly “de-selected” for Peace Corps service — that is, he almost didn’t “make the cut.” He writes that his close call came because his experiences with racist white people caused him to have “strong feelings against those who wanted to keep Black people in their place.”

“It never occurred to me that my attitude and behavior toward whites would reflect on the assessment of my fitness to be a Peace Corps volunteer who represented this country,” he writes early in the book. In a later chapter, he adds: “The Peace Corps blamed me rather than the society that had permanently injured me.”

The bulk of “Mission to Malawi” is dedicated to Fleming’s time in the country in which he served, as well as his visits to other African countries. He presents his memoir chronologically in four chapters, each of which is broken into smaller, subtitled sections, giving the work an episodic rhythm.

Humor, heartbreak and the humdrum of daily life come to the page as Fleming describes his first grudging taste of pan-fried grasshoppers; his disappointment that his then-girlfriend, Barbara, would not join him in Malawi; and the “culture shock” of learning how to keep a schedule in a country where work was traditionally not dictated by the hands of a clock.

Winding through these episodes, Fleming writes about how his perspective on the foundational racism of the United States was deepened by both his experiences in Malawi and news of the ongoing fight for civil rights at home. After learning of the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, he writes that he turned the lens of his grief toward his own work with the Peace Corps. At the time, he believed he had been “too silent and had acquiesced too often” when he encountered racism in Malawi, where Black people constituted the majority, but whites were “in control.”

“If I said that I loved Malawians, then I had to prove it by words and deeds,” he writes. “I knew that the changes I experienced with the death of Dr. King would be reflected in my relationships with white folks in Malawi.”

As readers of “Mission to Malawi” will discover, Fleming held true to that revelation, forming close relationships with Malawians and advocating for their agency in their own society and government. Before leaving Malawi, he made sure that his own post was not filled by another Peace Corps volunteer or European expatriate, but by an African diploma student.

He returned to the U.S. galvanized to continue working for social change. He soon took a job with Pride Inc., a Washington D.C.-based organization that, as Fleming writes, was “dedicated to working with the hardcore unemployed and unemployable, especially Black men.” He later earned his Ph.D. at Howard University, and went on to serve as director of many museums, including the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center and the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center in nearby Wilberforce.

Fleming said his time in the Peace Corps heavily shaped his life; much of his work in Malawi required him to learn through experience or teach himself new skills, and to build relationships across cultural divides.

“I’ve encouraged people who know me to read the book, and said, ‘This will give you a perspective on who I am, and how I developed over the years,’” Fleming said.

Despite his experiences with systemic racism and prejudice in the Peace Corps, as outlined in the book, Fleming said he believes his two years in Malawi were some of the most important in his life.

“I ran into some negative experiences, but by the time my term in the Peace Corps was up, the negative had turned into positive,” Fleming said. “What I truly believe about the Peace Corps experience is that it is beneficial to our life today.”

Ever the museum expert, Fleming mentioned the Museum of the Peace Corps Experience, which is currently being developed in Washington D.C.

“When we talk about why we should have a Museum of the Peace Corps Experience, it’s not just to recount the stories that volunteers had,” he said. “It is to show the impact of individuals on foreign communities, and that we can learn from our experiences, bring those experiences back to the U.S. and bring about social change in this country.”

“Mission to Malawi” is available for purchase via Amazon, and to borrow from the YS Community Library.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.