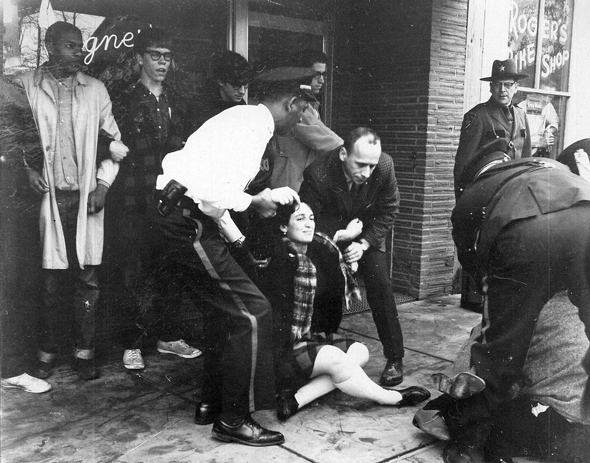

Police attempted to remove a protester in front of the Gegner Barbershop in 1964. Demonstrations against the local barber, who refused to cut the hair of Black people, escalated until a dramatic confrontation between 200 protesters and 150 area law enforcement on March 14, 1964. (Photo from the YS News archives)

Spring(s) | The meaning of protest

- Published: July 18, 2025

By Cyraina Johnson-Roullier

June 2025 was a month of escalating protests, like the pro-Palestinian protests on university campuses through spring and summer 2024, the protests surrounding the murder of George Floyd in spring 2020, the Black Lives Matter protests ongoing since 2013, the #Time’sUp protests (now defunct) and closely related #MeToo protests ongoing since 2006.

We can keep reaching backward to so many more, even to realize that the American Revolution itself, which resulted in the signing of the Declaration of Independence — the 249th anniversary of which we have just celebrated — was itself a protest against monarchical rule.

Having grown up in Yellow Springs during the protestive turmoil of the 1960s and the Civil Rights Movement, followed by the strong public opposition to the Vietnam War during the 1970s, I breathed the air of protest in nearly every waking moment.

The Yellow Springs community’s intense participation in those events was itself bolstered by that of Antioch College students and faculty. Close to the driving engine of the Civil Rights protests due to Coretta Scott King’s having attended Antioch, and her husband, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s having given its 1965 commencement speech, together the community and the school seemed almost a bull’s eye of unrest, and the constant immersion in this sentiment as a child made the atmosphere of protest deeply familiar after I went away to college, like a fond memory of home.

In my childish memory lies a sharp image of my mother, stalwartly marching in her bobby socks and pencil skirt with a sign held high, as part of the community-wide protest against Lewis Gegner’s barbershop, whose owner refused to cut the hair of Black customers, and whose later closing of the shop made national news.

That same sentiment returned each time I encountered protest thereafter. There it was when I happened upon the picket line of a small band of students at Ohio University, my undergraduate alma mater, in the years before Martin Luther King Day was established. And it was there again, more powerfully, many years later, when I found myself the only Black person in the room at the opening reception of an Association for Philosophy and Literature conference in Berkeley, California, as the violence of the Rodney King protests spread there from Los Angeles, and a terrified participant ran in to announce that rioters were outside.

Suddenly, silently yet subtly, as I have written elsewhere, I watched a wide semi-circle slowly open up around me, full of surreptitious, frightened and furtive glances, as if I were not simply a young assistant professor, but rather very much a representative of the enemy within, not for one moment to be trusted.

And it was there again in May, as soon as I arrived at the entrance to the Columbia University campus to begin a scheduled research trip in the Rare Books & Manuscripts reading room at Butler Library. The effort just to enter made evident that the university stood at the center of a number of extremely complex and volatile national and global arguments. I had known beforehand that the campus had been closed to the public since October of 2023, and by the beginning of May, it seemed things had calmed down. So I had performed the preliminary research necessary to make sure I had all the history, facts and names likely to be important to my efforts straight in my mind, studied the rules of access and, to the extent that I could from outside the university, figured out what I wanted to see. Even under normal circumstances, those protocols were complicated enough: setting up an online account so I could make a reading room appointment that would in turn let me request the necessary documents — and all needing to be arranged seven days in advance.

With that accomplished I was all set to go, so I was not prepared for the sudden news that 900 students had been evacuated from the Butler Library, the exact building I was intending to visit the following week, and that at least 78 people had been arrested, due to the entrance of a group of masked, drum-beating protesters with megaphones. But I had to make my peace with the fact that what I had thought would be the quiet, focused and productive business-as-usual activity that is a professor headed to the library on an archival research mission was perhaps not to be.

Yet as I later discovered, this mental preparation was still not enough to provide a full sense of the actual physical experience of the university’s public closure, the reasons why, what it would look and feel like and the incongruity between this and the institution’s intellectual and academic relationship to my own research interests.

The entry to the Morningside Heights campus at 116th and Broadway saw a long line of would-be entrants like myself bounded by several security personnel, one in a roofed structure with a sliding window, two more at a card table, and yet another one intently watching the narrow gate leading into campus — two more standing on either side of the line.

When I presented my ID and appointment confirmation, I was directed to the person in the roofed structure, who was supposed to have my name, but didn’t, who looked skeptically at my information, listened politely to my story, then said that entry could only be granted with a QR code that I should have received from the library (I hadn’t). After about an hour I finally received a code by email, but then entry was still delayed because it didn’t work.

Confronting these issues, the result of months of protest, I would do so yet again once in the reading room with the Moncure Conway Papers, themselves a historical representation of protest uniquely tied to Yellow Springs because of the Conway Colony, which Moncure Conway, the second son of a patrician Southern family, established there in 1862. With the Civil War raging around him — yet another protest — Conway, a staunch abolitionist though deeply Southern, brought 30 of his father’s slaves to Ohio to settle in Yellow Springs, where many of their descendants remain.

For his actions and ideas — his personal protest — Conway paid the heavy price of exile from family and country, and later literary obscurity. But he gained far more, in defense of his own personal integrity.

Pondering his experience, I’ve realized that, like Conway, as an African American woman my own encounters with protest are and have been both public and personal, and sometimes even tiny, in the moment.

Yours may be, too.

*Cyraina Johnson-Roullier is Associate Professor of Modern Literature and Literature of the Americas at the University of Notre Dame.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.