BLOG-Inch by Inch

- Published: May 10, 2014

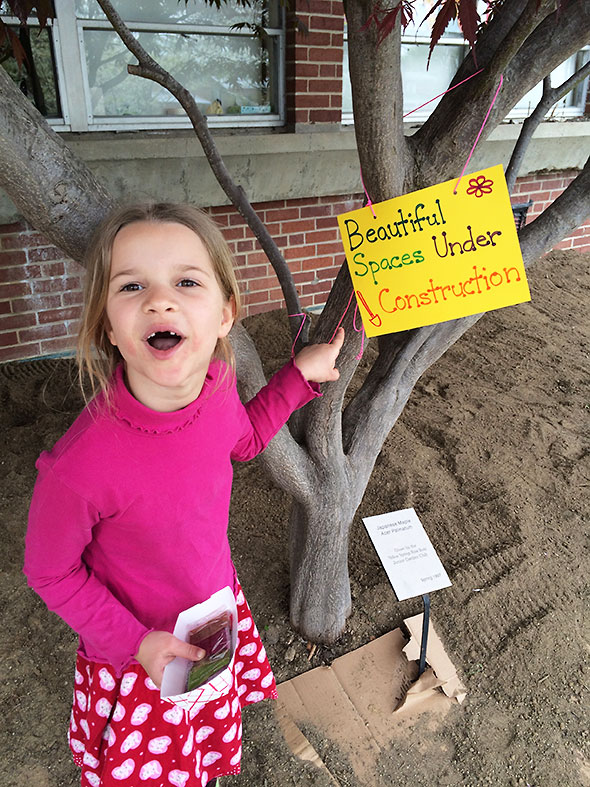

Friday morning and into the afternoon before the rains came, the first grade class of Mills Lawn School took over the east lawn of the school armed to the teeth with shovels, rakes, wheelbarrows, and purpose. They seized control of the garden plot by the school’s main entrance and removed every trace of green-growing life from the bed leaving only the red-leaf Japanese Maple tree. They covered the bare ground with flatten, torn cardboard boxes to serve as a weed barrier and a clear delineation between the past and the future.

Friday morning and into the afternoon before the rains came, the first grade class of Mills Lawn School took over the east lawn of the school armed to the teeth with shovels, rakes, wheelbarrows, and purpose. They seized control of the garden plot by the school’s main entrance and removed every trace of green-growing life from the bed leaving only the red-leaf Japanese Maple tree. They covered the bare ground with flatten, torn cardboard boxes to serve as a weed barrier and a clear delineation between the past and the future.

In shifts of twenty children at a time, they took up shovels and rakes, piled the fresh dirt high on top of the cardboard, and then smoothed the new soil in a graded slope up towards the school. They worked steadily—in close but conscientious quarters—and without fuss swung shift changes every 10 minutes. Each group set directly to work filling the wheelbarrows and shaping the new contours of their garden. Ms Simms and Mrs Scavone established a contagious rhythm, and many of the children hummed a familiar and favorite tune as they set to their occupation: “Inch by inch, row by row, going to make this garden grow. All it takes is a rake and a hoe and a piece of fertile land.” In The Garden Song by David Mallett, they found the clear expression of their purpose and the freshly mulched underpinnings of their transformative power.

They ate lunch outside in the seat of their endeavors looking on the progress made and thrilled at having these long revered adult tools finally placed into their eager hands. Only when the rain started did they come indoors. Just one door inside within Ms Denmen’s kindergarden classroom, the three classes of the first grade sat down together and watched a documentary about a wise-cracking teenage boy who had channelled his life long love of garbage trucks into raising worms on compostable trash. Ms Denmen opened up her classroom worm farm and showed the children its wriggling inhabitants. She allowed the children lingering whiffs of the nutrient-rich compost tea—aka worm pee—and the soil-like worm castings that collected at the base of the farm’s stacked architecture. Not a single “ew” rose from the children. Ms Denmen’s treasure box and its inhabitants were too cool, and the children jockeyed for position and favor as Ms Denmen revealed its inner chambers. The three classes sat attentively around her and discussed what they knew about the way the worms ate, how they lived, and how they contributed to the land. Ms Denmen couldn’t answer every question but together the children and teachers agreed to research worm farms further and fill in their understanding. They also wholeheartily agreed to feed the critters a weekly dose of compostable food waste and infuse the garden an enriching dose of worm’s castings. Row by row, the children’s resolve bubbled effervescent.

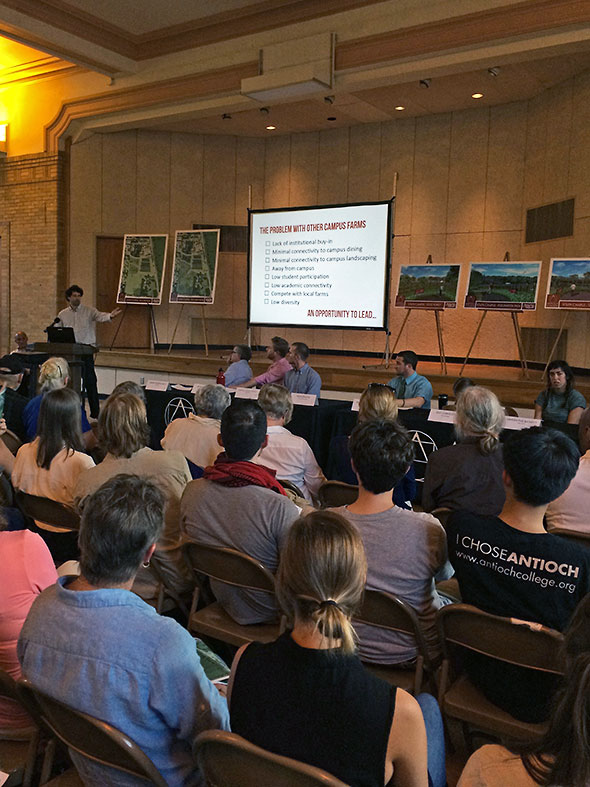

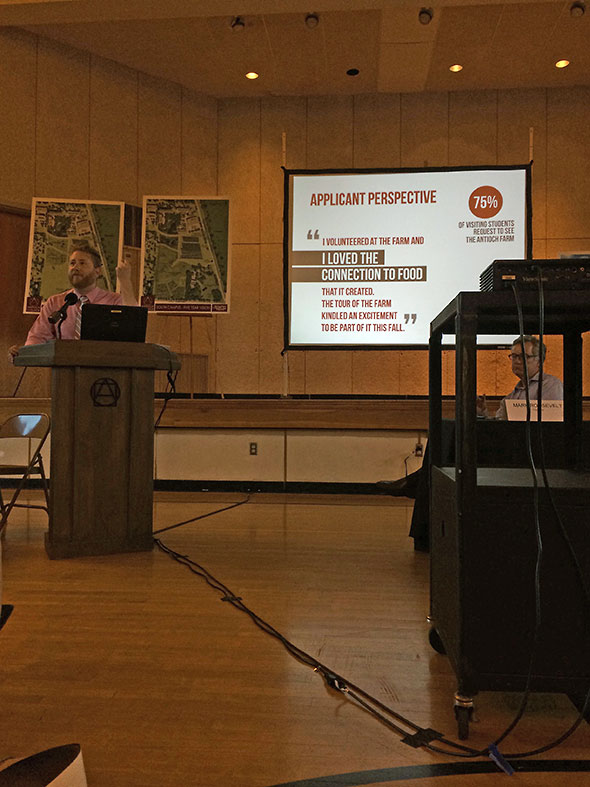

That same level of purpose-driven resolve was brought by Antioch students Thursday night to the John Bryan Center. Students, instructors, and administrators from Antioch College organized a detailed presentation on the College’s Campus Farm. They covered both the farm’s progress in its first two growing seasons and depictions of farm’s metamorphosis through the next five.

The College’s Five Year Plan for the “golf course”—the 36-acre field on the south end of campus—fits the model of Urban Agriculture which, in its ambitious forms, practices both crop and animal husbandry near residential housing. As I learned just last week in the National Convention of community land trusts, Urban Agriculture is an integral part of the mission that Community Trusts enact—rescuing abandoned city blocks and building diverse, sustainable communities—and exactly the kind of “inch by inch” activism that Antioch College lives and breathes to advance.

The most unexpected element and thus most evident opportunity that Antioch College adds to its agriculture curriculum is the inclusion of green power production. A forest of solar panels directly adjacent to the Campus Farm offers the campus a significant source of electrical power under its own meter, and its proximity to the farm spurs the imagination in how it might help the college’s educational and research goals. The diverse ecology of the polyculture farm can be instrumentalized; the activities of animals and the progress of crops can be tracked and streamed online. We’d have ready resources for smart irrigation: The slanted profiles of the solar panels—made of common materials steel, aluminum, and polysilicon—make them suitable for rainwater collection; sufficient power will be available onsite to not only pump the water where it needs to go but also to compute when and how much water is needed.

The activists at work on the Campus Farm intended it as a disruptive force that will reshape the American food system and redirect it from the unsustainable path of the past thirty years. To its neighbors and host community of Yellow Springs, the farm is intended not as a disruption but as a source of beauty, education, and empowerment. Done well, the farm will add value to properties that immediately surround it and enhance the quality of life for both those who produce within it and partake from it.

I know this ambition is achievable because I have seen its vision realized at Smaller Footprint—the no-till, sustainable farm that farmer and Antioch Farm Manager Kat Christian built north of town with her husband Doug. I would not feel safe working on most conventional farms, but I have worked at Smaller Footprint in comfort and harmony with nature. The farm is located in a more traditional rural setting and, in that space, the Christians have been able to dry run the practices of rotating grazing pens and crop beds. I have worked mulching beds for vegetables and harvesting produce while chickens and pigs foraged in their nearby pens. The only unpleasant smell that I had to deal with was from my own sweat of labor.

I have great confidence in the ability of Kat Christian to translate her farming practices to urban farming. This confidence is won not only from working with Kat but from my own experience growing up in an agricultural community that values organic methods. As a very young child, I lived in a house surrounded by corn fields and dairy farms. Back in those days, one of the Twiggs’ cows would occasionally get loose, and once or twice we gave Harvey a friendly call to come and collect his milker. We’d react to the situation much like we’d react to a deer moving through the yard: with wonder, interest, and the appropriate amount of caution.

I’ve long considered the proximity of working farms part of Yellow Springs’ distinct charm. I live on the south side of Yellow Springs where I can hear cows moo from my front porch. I consider that idyllic but some villagers are not comfortable with the changes that are unfurling in their backyard and with the prospect of having as many as 2 cows, 5 pigs, 50 ewe, 30 goats, and 150 poultry birds as neighbors. These new neighbors are not going to arrive all at once but in a graded fashion. As the college tests the estimate of the land’s capacity against practical reality, the neighbors’ present discomfort in uncertainty is understandable. I will even point out how their presence and continued feedback are extremely valuable. Academia needs its skeptics, and Antioch’s uneasy neighbors are but a small part of the audience that Antioch has to reach and win over in the quest of transforming agriculture. Our community can help out by valuing the important role of the observant skeptic as Antioch College adds to the farm inch by inch, row by row, and to continue to hold respectful debates on the farm’s ventures.

Many of us will miss the open fields of the golf course…the vistas it offers, the walking space, the quiet harmony…but the college’s ambitions fulfill a vital mission which takes me back to the first time I heard The Garden Song. Pete Seeger sang this version and his words were slightly different, his meaning measurably more powerful.

Inch by inch, row by row

Going to make this garden grow,

Going to mulch it deep and low,

Going to MAKE it fertile ground.

Conventional farming drains nutrients from the soil and the health from its workers and their communities. We can make a better bargain with farm workers and with ourselves by supporting a food system that enriches the soils, the farms, the neighborhoods, and the communities it serves.

Inch by inch, row by row

Please bless these seeds I sow.

Please keep them safe below

Til the rain comes tumbling down.

In the song, a crow watches from a nearby tree and thinks that it has a better use for the seeds that the farmer is planting. Both uses are good but, if a seed is allowed to sprout and go to seed again, it will feed more than just the crow and more than the farmer too.

As we watch and wait with patience for the first grade class to take blank cardboard and bare soil to a colorful patch of beautiful, I ask for the same courageous vigilance as we watch Antioch College. They aim to create something beautiful and new and to sustain it.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.