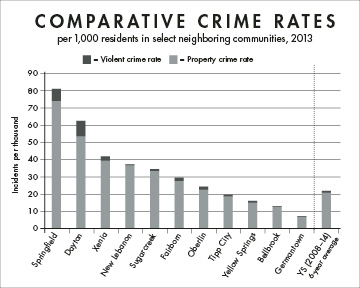

Rates of property and violent crime per 1,000 residents in select neighboring communities and small towns in the state. SOURCE: FBI Uniform Crime Reporting‘s “Crime in the U.S. 2013” Yellow Springs figures from 2013 amended using YSPD data. Yellow Springs seven-year average created using FBI & YSPD data.

Balancing a low crime rate with high policing costs

- Published: March 26, 2015

POLICE MATTERS

This is the third in a series of articles

examining the local police department and its relationship to the village.

• Click here to view all the articles the series

People getting shot, drug dealers slinging crack-cocaine and neighbors not trusting one other enough to share their phone numbers.

That was the experience of Yellow Springs Police Chief David Hale in his 30-year law enforcement career in Montgomery County — a far cry from Hale’s last six months in the village. Instead, Yellow Springs is, by most measures, a safe community where neighbors look out for each other, which Hale called a “refreshing change of pace” this week.

The numbers bear out the difference. While last year there were 28 murders in the City of Dayton and more than 1,200 violent crimes there, violence in Yellow Springs has barely been an issue, with an average of about three violent incidents each year for the last seven. Rates of property crime — the most statistically-significant threat to villagers — are well below those of nearby communities, less than state and national averages and on par with other small towns.

But at the same time, the Village employs more full-time police officers and total public safety employees per capita than most other area towns and cities, while its staffing levels are close to the national average among similarly-sized municipalities. The Village also likely spends more per capita on policing than the national average — last year local police cost each resident $350.

If Yellow Springs is safer than other towns, why does it need more officers and a larger police budget to protect its residents?

Hale, who said he is happy with the present size of the police force at 10 full-time officers, cited several reasons why Yellow Springs may need more officers per capita despite low crime rates. For one, the large number of tourists that flock here creates the potential for more crime, though tourists don’t necessarily commit violent or property crimes, he said.

“My job is contingencies,” Hale explained. “Think of what would happen in the middle of Street Fair if someone fired off a few rounds — that’s quite a bit of havoc.”

Hale added that while crime rates are “pretty low” in Yellow Springs, violent crimes or serious thefts can, and do occur here. For example, there were two murders in the village in the early 2000s. In 2013, nine homes were burglarized and last year two motor vehicles were stolen and 10 broken into in separate crime sprees that were both connected to individuals with drug addictions. For Hale, local police need to be well trained and ready for the next rash of crime, whenever it occurs.

“Yellow Springs is, by and large, somewhat insulated from a lot of the violence [in the region,] but it doesn’t mean that it won’t happen,” Hale said. “My job is to have [my officers] ready for the big one.”

But with most YSPD activity connected to traffic stops and miscellaneous activities from house checks to road clearances, some villagers are beginning to question the size and expense of the local department. Local resident Isaac DeLamatre, who is completing a qualitative survey of villagers’ experiences with local police, sees that making the town a safer place need not rely on the police.

“The results of my investigation indicate that police are largely unnecessary in the village,” DeLamatre wrote in an email this week. “Rather, the village seems to have more need for social workers, mental health professionals and non-law enforcement emergency responders.”

When it comes to cutting down Yellow Springs’ already low crime rate, Hale added that much can be done by villagers themselves, who can be on the watch for suspicious behavior in their neighborhoods and report tips to police. Ultimately, it comes down to a community where people trust each other, and the local police, Hale said.

“So much of police work deals with areas where there is less trust,” Hale said. “In Yellow Springs, it has been nice to restore my faith in humanity.”

Crime remains low here

Property crime, which has been on a downward trend in the village and nation for the last decade, remains low in Yellow Springs compared with other communities. Meanwhile, violent crime is even more rare here.

According to figures recently released by the Village, there were 75 property crimes last year (including 60 thefts, 7 burglaries and 8 motor vehicle thefts), compared with 56 in 2013 and 62 in 2012. Back in 2008, there were 109 property crimes here, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s annual Uniform Crime Report. Nationally, property crime has fallen by 16 percent over 10 years, the FBI reported.

Using the seven-year average, Yellow Springs’ annual property crime rate of 21.4 incidents per 1,000 residents is still below the 2013 average for Ohio (29.3) and the U.S. (27.3), while it pales in comparison to nearby Springfield (74.4), Dayton (54.2), Xenia (40.3), and Fairborn (28.2). Using just FBI data, which automatically downloads reports from local police computers each year, Yellow Springs’ 2013 property crime rate could be as low as 7.0 per 1,000 residents, while Village data gives a rate of 15.8. Using Yellow Springs data alone, last year’s rate was 21.2.

Yellow Springs is about as safe as other small towns in the state and region. Depending upon which figures are used, the property crime rate in the village appears to be higher than places like Bellbrook (13.2 in 2013) and Germantown (7.61), on par with Oberlin (23.1) and Tipp City (19.3) and safer than Sugarcreek (34.1) and New Lebanon (37.3).

According to an annual report from the YSPD, the value of stolen merchandise reported to the police in 2014 was $128,060, of which $77,817, or 60 percent, was recovered. The value of unrecovered property last year amounts to about $14 per resident. There were also 17 incidents of criminal damaging last year, which includes vandalism, up from eight in 2013.

Property crime and damage, however, takes its toll in other ways, Hale said. Especially when one’s home is broken into, the psychological damage can be severe, which is why Hale said he takes home burglaries so seriously. Outside of truly violent crimes, Hale said he dislikes burglaries the most because they can be “so devastating to people.”

“Your home is psychologically your sanctuary so when it is violated, when someone enters into the home where you raise your family and spend time with your loved ones, that is very tough,” Hale said.

When it comes to violent crime, which the FBI defines as murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault, Yellow Springs has had just two to five incidents per year since 2008 for an annual average of around three per year. That gives the village a rate of 0.9 incidents per 1,000 residents, which is less than 2013 averages in Ohio (2.8) and the nation (3.7), well below Dayton (8.7), Springfield (7.1), similar to Tipp City (0.9), Sugarcreek (1.1) and above Germantown (0.2) and Bellbrook (0.3).

According to YSPD figures, last year’s two felonious assaults were the only violent crimes in town, while there were 15 misdemeanor assaults, which legally includes attempting to harm someone. Of those, five were incidents of domestic violence.

Police activity in town

With so little crime in town, what do local police officers spend their time doing? According to the village’s report, last year there were 1,972 offenses reported, 1,488 total citations issued and 10,403 calls for service received by the department, an average of close to 30 per day. There were also 67 car accidents and hit and runs in town, 11 where injury occurred.

According to dispatch reports, most of the time the YSPD deals with barking dogs, loud music, dead animals obstructing roadways, stolen bicycles, lockouts and door checks. Hale added the department engages in other miscellaneous activities like issuing warrants and parking violations, assisting the Miami Township Fire and Rescue squad on its calls, visiting the schools during the day and the bars at night or checking the doors of downtown businesses overnight.

Especially with such low crime rates, it is exceedingly rare for a police officer to happen upon a crime in progress here, Hale said. That’s why traffic stops have become a critical tactic to root out lawbreakers and deter crime in the village, he added.

“You don’t trip over that many crimes in progress,” Hale said. “The stop is how proactive police work gets done. It’s how we prevent crime.”

Last year the police made 1,193 traffic stops, issuing citations in 187 of the stops, while giving warnings 84 percent of the time. That was on par with the close to 1,000 warnings issued in 2012 and less than the 1,419 warnings in 2013 during former Chief Tony Pettiford’s tenure.

According to Hale, police can stop motorists for any number of infractions, including, most commonly, a defective brake light or license plate light, cracked windshield along with speeding, signaling or stopping violations. Hale defended the use of traffic stops because they can lead to drug-related citations or arrests. He also said that the stops disproportionately affect low-income people and younger people because their cars are more prone to defects while they are more likely to let vehicle problems go unfixed.

Hale added that officers are not expected to meet a quota of traffic stops or citations but are given a lot of discretion over whether or not to pull someone over and whether or not to give them a ticket. Generally, police warn speeders if they are less than 15 miles per hour over the speed limit, though there are exceptions in residential areas. Previously, the police have maintained that the money raised from tickets does not even cover the cost of Mayor’s Court, let alone police activities.

When it comes to whether an officer will issue a ticket, search a car or take any other action, Hale said he gives his patrol officers a great deal of discretion so they learn policing.

“I want to produce intelligent cops,” Hale said. “While they need to understand my expectations, I want to give them the freedom to evaluate the circumstances.”

Staffing, funding the YSPD

The Yellow Springs police department currently has 10 full-time sworn officers (including Hale), four part-time sworn auxiliary officers and five civilian part-time dispatchers, according to Hale. While he is pleased with the level of staffing, according to some figures YSPD is relatively large.

If counting only full-time officers, Yellow Springs currently has 2.8 officers per 1,000 inhabitants, higher than the nationwide average in 2013 of 2.3 and the statewide figure of 2.4. Using FBI figures, Yellow Springs had 11 total full-time employees in 2013 for a rate of 3.1 employees per 1,000 inhabitants. That’s less than the 3.4 national average but higher than several nearby jurisdictions, including Springfield (2.4) and Fairborn (1.7), and other small towns like Oberlin (2.8), Sugarcreek Township (2.2) and Bellbrook (1.8).

For comparison, Bellbrook, which has double the population of Yellow Springs at around 7,000 residents, had 10 full-time and one part-time officer in 2013, according to its annual report, less than the 14 full and part-time officers in Yellow Springs. Last year Bellbrook also closed its dispatch center and began contracting with Xenia in a move Bellbrook estimated could save its department $150,000 annually.

While Yellow Springs may have more officers and law enforcement employees per capita than other area towns, it may have about as many as can be expected for a town with less than 10,000 inhabitants. Nationally, that rate is 3.5 officers per 1,000 inhabitants (2.7 in the Midwest) and 4.5 total employees (3.2 in the Midwest). But if the part-time dispatchers and officers are counted at one-half time, Yellow Springs could have upwards of 4 employees per 1,000 residents and 3.4 officers.

But Hale cautioned against making comparisons with other towns that don’t have the same tourist draw as Yellow Springs. He estimated that the population of the village can swell to upwards of 12,000 and when compared to municipalities of that size, Yellow Springs is actually understaffed.

Hale added that because Yellow Springs is a small town with little serious crime, the local police department is a “feeder agency” to larger police departments, and thus has a high turnover rate. The local force is also young, with five first-year police officers now in the department, who require additional training from more veteran police officers. The level of staffing guarantees that relatively-inexperienced officers aren’t on their own on busy Friday nights, which Hale said makes him uncomfortable.

While statistics comparing the per-resident cost of local police departments are not easily available, a 2008 Bureau of Justice Statistics nationwide survey of 12,501 municipal and police departments found operating costs were $116,500 per sworn officer and $260 per resident. A Columbus Dispatch study last year found the average cost per resident for policing in 53 central Ohio departments in 2013 was $251 per resident.

In 2014, Village of Yellow Springs spent $1.25 million on public safety, ($1.1 million or 88 percent, on personnel), which comes to $124,162 per sworn officer and $350 per resident. If the local police department spends its entire 2015 budget of $1.33 million, policing could cost $377 per resident this year.

Note: Per capita calculations are based upon the FBI’s 2013 population estimates, which for Yellow Springs was 3,539.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.