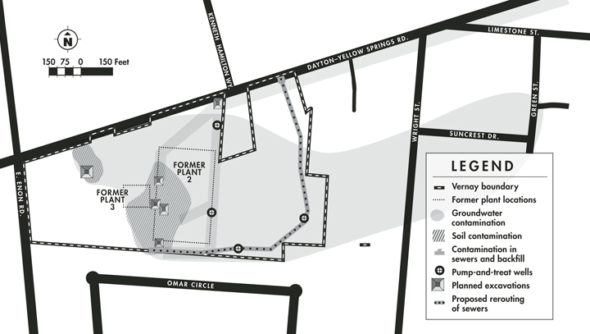

At Vernay’s former rubber parts manufacturing facility, volatile organic chemicals are present in the groundwater below and extending to the east of the site, in the soil and bedrock, and in sewers and their backfill. In it latest plan to clean up the site, Vernay is proposing to excavate contaminated soil in six areas, re-route the existing sewer line and continue pump-and-treat wells, among other activities. (Map created using data and graphics from Vernay and EHS Technology Group)

EPA to address latest Vernay cleanup plan

- Published: October 24, 2019

Click here for a larger PDF of the above map.

When he joined the Yellow Springs Environmental Commission, Tom Dietrich was surprised to learn the status of the environmental cleanup at the former Vernay Laboratories site on Dayton Street — that the property had yet to be remediated.

It’s a misconception he believes many villagers share.

“I think there’s a common misperception that it had been cleaned up,” he said. “I thought it had been cleaned up.”

Two decades have passed since extensive contamination was discovered at the former rubber manufacturing facility. Under order from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Vernay has taken steps to stem the flow of contaminants in the groundwater under residential neighborhoods. At the same time, the company — which has since closed and demolished the plants and moved its operations to Georgia — has been working on a final cleanup plan with the EPA.

That process may be nearing its end in early 2020, according to EPA representatives. As a result, the agency is coming back to town next week to update the community on the status, and present the current version of the cleanup plan.

“We haven’t been out in a dog’s age,” said Rafael Gonzalez, the EPA’s community involvement coordinator.

The U.S. EPA will host an information session on Thursday, Oct. 24, from 5 to 7 p.m., in rooms A & B of the Bryan Center.

Gonzalez, who is based in the Region 5 office in Chicago, described the meeting’s purpose as two-fold. He said he wants to bring the community up to date on “where we are in the process and where we are going,” and also to hear from villagers.

“I need to get a feel for how the community feels about this,” he said.

This week, Village leaders encouraged residents to attend, and also affirmed the Village’s interest in a long-term cleanup of the 18–acre property.

Village Manager Josue Salmeron said that no matter how long the cleanup takes, the Village “wants to see it done well.”

“We are taking our responsibility seriously to protect the residents, the Village and the environment,” he said.

Dietrich, who has led an Environmental Commission effort to comment on Vernay’s plans in recent years, also hopes for a good turnout.

“I think this is something everyone in the village should be concerned about,” he said. “I would like to see a very strong showing that this is an important issue to the village.”

As the EPA and Vernay come closer to agreeing on a final remedy for the site, questions are being raised about whether or not the proposed strategies will protect human health and the environment. This week’s article looks at some of them.

The history

Incubated at Antioch College by inventor Sergius Vernet, Vernay officially incorporated in 1946, setting up an experimental laboratory on East South College Street.

Vernet had invented a new thermostat that is still used in cars today, according to a history of the company. Then, in 1951, the company moved to 875 Dayton St. and began manufacturing rubber-molded parts for the automotive, appliance and medical industries, at the time dominating the industry in “fluid-control solutions.”

Vernet established a union at the factory, and the company became known for its progressive efforts to hire and support a diverse workforce and for its philanthropy through the Vernay Foundation. For decades it was one of the town’s largest employers. Vernet died in 1968.

Vernay employees first discovered contamination at its site in 1989, but company leaders waited nearly a decade to investigate the full extent and location of contamination, according to internal memos released by the Sierra Club in 2003.

Those contaminants of concern found in soil, water and bedrock at the site include chlorinated solvents such as trichloroethylene, or TCE, and perchloroethylene, or PCE, used for decades to degrease metal parts at the factory, their breakdown product, vinyl chloride, and several other volatile organic compounds, or VOCs. In addition a common pesticide was found.

The EPA considers TCE to be “carcinogenic to humans,” with links to cancers of the kidney, liver, cervix and lymphatic systems. PCE, meanwhile, is “likely carcinogenic” and impacts the nervous system and liver, according to the EPA’s Integrated Risk Information System. Vinyl chloride is carcinogenic to the liver, according to the Center for Disease Control’s Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, while other VOCs found can harm the cardiovascular, neurological and respiratory systems.

Vernay began cleanup efforts in 1998 through Ohio EPA’s Voluntary Action Program. At around the same time, the U.S. EPA became involved, evaluating the site for the Superfund program. Then, a group of neighbors filed a suit against the company and requested a cleanup process overseen by the U.S. EPA. In addition to agreeing to the cleanup, Vernay paid $850,000 in attorney fees, an undisclosed amount to six plaintiffs, a $25,000 fine for violating the Clean Water Act and $455,000 to be used by neighbors for oversight of the cleanup.

In 2003, Vernay, which had been planning to move its Yellow Springs production operations to plants in Georgia and South Carolina, began to close the two plants operating at the site, and 185 employees subsequently lost their jobs, according to News articles at the time. In 2009, the plants were demolished, but Vernay still kept its corporate headquarters and small R&D operation at its original facility on East South College Street.

Vernay’s headquarters are now in Atlanta, Ga., and the company maintains plants in Georgia, Italy, the Netherlands, Japan, Singapore and China, and offices in France, Brazil and Korea, according to its website. Although more than 60 employees were still based locally as of 2004, today just two employees remain at the original Vernay facility, according to a spokesperson for Vernay this week.

Interim cleanup activities

As a result of the lawsuit, in 2002, Vernay began work on the cleanup under an order of consent with the U.S. EPA through the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act.

Vernay set out to investigate the scope of contamination and, ultimately, prepare a final cleanup plan known as a Corrective Measures Proposal. That proposal was first drafted in 2009; its latest iteration was submitted in June.

The company also instituted interim measures to contain the plume of contaminants in groundwater in the Cedarville Aquifer under its property from spreading. In 2002 and 2003, Vernay installed two capture wells on its property, and added two more in 2011 after purchasing an adjacent property. The wells pull up contaminated water, use an activated carbon filter to remove the chemicals, and discharge it to the Village’s sanitary sewer. As of July, more than 200 million gallons of groundwater have been treated, according to the EPA.

The “pump-and-treat” system is slowing the movement of the plume, where VOCs in the groundwater exceed the EPA’s maximum contaminant level of five parts per billion, according to the EPA. That plume now extends across Wright Street and Suncrest Drive to Green Street.

In addition, Vernay continues to survey and test private wells in the area, only two of which were still being used as of 2019. And it monitors the plume’s spread in 45 monitoring wells on and off of its property.

In a letter to the EPA this year, Vernay wrote that “early interim actions helped control migration of impacted groundwater into the surrounding neighborhood.” According to the EPA’s website, human exposure to the contaminants of concern in the area has been “under control” since 2008.

This week, Vernay spokesperson Dan Williamson contended that those interim measures are keeping people safe.

“While the cleanup below the site continues, folks in Yellow Springs should know that their drinking water is safe and their air is safe,” Williamson said.

Ongoing concerns for human health

Others who are monitoring the cleanup are not convinced that the interim measures are having much impact on either containing the plume, or keeping people from the potential for harm.

One such group is EHS, a Dayton firm hired to oversee the cleanup with funds from a lawsuit settlement between Vernay and the group of neighbors.

For years, EHS has argued that the plume was not contained, but continuing to spread, calculating that the “zone of capture” for each well extended just 80 feet, far less than Vernay had claimed.

David Altman, the attorney representing the neighbors who settled with Vernay, said the expansion of the plume is clear, and worrisome.

“It’s absolutely clear that stuff is escaping to the east,” he said in a recent interview. “The data shows that’s what’s happening.”

And while residents who live on or near a plume aren’t drinking the contaminated water, they could be exposed to the chemicals through the air. That’s a concern for Denise Taylor, a University of Dayton professor of environmental engineering who is working with the Village to review Vernay’s plan.

“The chemicals are volatile in nature and they evaporate quickly,” Taylor explained. “But if they evaporate into your house instead of out of your house, there is the potential for contamination.”

Known as “vapor intrusion,” the EPA began to more seriously study the threat about a decade ago and released a long-awaited guidance document on the topic in 2015.

As a result, the EPA ordered Vernay to begin testing for vapor intrusion. Between 2016 and 2018, Vernay tested wells both on and off of its property, along with at least three private residences in the area.

While there were a handful of instances when a contaminant was measured above Ohio EPA response action levels, overall the tests proved to the EPA that vapor intrusion was not an immediate danger to area residents.

“At the Vernay site, the sample data has not led EPA to conclude that vapor intrusion constitutes an immediate health threat,” the EPA told the News in 2017.

But extremely high concentrations of soil gas in a test well immediately north of residential property lines on Omar Circle led EHS to conclude that the EPA should move quickly to push for a thorough site cleanup.

The potential for vapor intrusion still exists, Taylor believes, and can affect homes both above and near a groundwater plume as the vapors travel along “preferential pathways” such as sewer and water lines, according to EPA reports.

“There is not yet any high vapor intrusion in homes, but as the plumes move there is potential for it,” she said.

In addition, highly contaminated soils on the site have continued to flush contaminants into local sewers and waterways, EHS has argued. That flushing was hastened by the 2009 demolishing of the structures on the property, the group has contended.

The latest cleanup plan

Vernay’s latest plan to clean up contamination at the property includes a variety of measures that the oversight group, EHS, and the Village Environmental Commission have been pushing for. But they don’t go far enough, those groups believe.

According to its 142-page plan, Vernay will continue to operate its four pump-and-treat wells; remove contaminated soil in six “hot spots” on the property; dismantle an existing storm sewer system and other underground infrastructure, and reroute a sewer line from Omar Circle to Dayton Street.

“This is a comprehensive approach to address all media with technical approaches with demonstrated effectiveness,” Vernay wrote of the measures in its report.

Vernay estimates the total cost of the measures to be $7.4 million for the first 30 years, of which $1.2 to $1.4 million is for soil excavation and sewer source remediation. According to a draft timeline, the measures could be completed as soon as March 2021.

In addition, Vernay is hoping the Village will pass a well-capping ordinance to prevent villagers from tapping into contaminated groundwater and to seal existing wells in the area. And they would add covenants to the property restricting it to industrial and commercial uses.

“Vernay feels like the plan that it has put forth is a good plan,” its spokesperson said this week.

Soil excavation — Excavation of contaminated soils at the site has been urged by EHS for years. But the current plan cleans soils to a “non-protectively high standard,” EHS wrote in an August letter, leading to the likelihood that contaminants might remain in the soil and thus continue to leach into the groundwater.

Altman said his clients are suggesting six additional areas to excavate, which he said is “more than what Vernay is proposing but still a finite amount of work.” Altman estimated that the total volume of soil to be removed is about “three football fields of dirt” and would only double the cost of excavating.

Especially concerning is contamination between the former plant buildings, according to Abinash Agrawal, a Wright State University professor who specializes in contaminated sites and is reviewing the plan for the Village.

“The contamination at those locations has gone very deep,” he said, pointing to an area where contaminants reach concentrations of more than 100,000 parts per billion.

“My fear is the excavation will fall short,” he added, especially as workers strike the limestone bedrock and are unable to continue. As a result, “they need to come up with a plan that destroys the contaminant in its place,” Agrawal said.

Dietrich echoed the concern about leaving contamination in the underlying bedrock, which he said might continue to contaminate the groundwater.

“The Vernay report indicates there are pollutants in the bedrock but it doesn’t say they will do anything about it,” Dietrich said.

On the issue, Vernay quotes the EPA itself in saying that removing contamination from the bedrock is “not likely to be achieved within a reasonable time frame.”

Pump and treat — When it comes to the migrating contaminant plume, Vernay’s plan is to continue its pump-and-treat system and let natural processes do the rest. But several interviewed this week questioned whether that was sufficient.

Vernay has claimed that a combination of the capture wells and “natural attenuation” will reduce contaminant concentrations in the groundwater, making it safe to drink from the plume off of its property in about 30 years. The company plans to continue to pump and treat on the property for another 30 years, to potentially improve groundwater on the property itself.

Agrawal was critical of those plans, saying, generally, that “pump-and-treat has failed miserably in addressing solvent contamination.” That’s because contaminants are not soluble, but instead tend to stick to soil.

“This is an archaic approach that is not very effective anymore,” Agrawal said.

Taylor, who has studied biological processes at contaminated sites, added that “natural attenuation by itself is not enough.”

“Because the concentrations are so high in some areas, there are not currently bacteria evolved enough that can degrade that pocket of material,” she said. “Bacterial attenuation can help polish the site, but the very strong contaminants need to be controlled in other ways.”

EHS has argued for additional capture wells in the areas between the existing wells, where they believe contaminated groundwater is escaping the property.

Sewer rerouting — Vernay’s plan to reroute the sewer system was noted as a positive area of the plan. The company is looking to dramatically change the water drainage at the site, collecting water into a central area, then piping it along the rear and eastern portions of the property before it empties into a storm sewer on Dayton Street.

As Taylor put it, “the old sewer was essentially acting like a highway,” quickly drawing contaminated water into public sewers and waterways. The new plan, however, slows the process and re-directs water from the highly contaminated existing routes.

Although the Village has previously raised questions about the viability of the proposed stormwater management at the site, Village Public Works Director Johnnie Burn said this week that a cursory review shows that it may actually improve stormwater management on the property.

EHS favors the proposal, but asks that additional underground infrastructure be removed to reduce the number of possible routes for contaminated water to flow.

Next steps

If the EPA accepts Vernay’s latest plan, the agency will release a “statement of basis.” That document is the “culmination of years of work at the site by federal, state and Vernay representatives,” according to the EPA. A public comment period on that document could take place as early as next spring.

Asked about the long timeline, EPA spokesperson Joshua Singer wrote in an email that “the remediation process can take a significant amount of time.”

“The time frame is dependent on the nature and extent of the contamination, the complexity of the site, and other related factors,” he wrote.

Williamson, who works with a Columbus-based PR firm recently hired to speak for Vernay, said the company understands villagers’ frustration with slow progress at the site. He added that he hopes that the relationship between the village and Vernay can improve.

“It’s clear that the pollution and Vernay’s initial action upon discovering contamination changed the relationship with the village,” he said.

“Relationships take time to heal and it’s going to take actions more than words,” Williamson added. “Vernay’s hope is that the cleanup efforts it’s undertaking now and its future actions will be steps in the right direction.”

Village Manager Salmeron said he hopes to restart communication with Vernay, which he said is “a central part of the solution.”

“We are hoping to work on that relationship,” he said. “There has been a breakdown and that goodwill has deteriorated.”

Williamson said that although Vernay does not have a formal role at the meeting, several Vernay representatives will be in attendance.

As for villagers, attending could be an important way to have a voice in the final remediation, according to Taylor.

“It’s important for Yellow Springs residents to put the public face on it,” she said. “You all are the ones dealing with the consequences.”

Contact: mbachman@ysnews.com

3 Responses to “EPA to address latest Vernay cleanup plan”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

Spring of 2022 – I’ve checked the EPA website and any other reports in the news or with the village government – this article is in 2019 and so is the EPA report. The village website states a Grant Application was submitted in 2020 to the EPA. Dr. Agrawal has some excellent suggestions. What are the latest updates on this brownfield mess?

Dear Dr. AGRAWAL,

During the August 2021 Ohio Pollinator Habitat Initiative (OPHI) Symposium, a presentation re: restoration of brownfield discussed a current project studying the health of growing native plants, and the potential of residual TCE & other contaminants in insects, etc. They haven’t completed their study. They cited a paper from Utah showing apple & pear trees grown on such a brownfield had TCEs and contaminants in the roots but not the fruits or leaves. The mechanism of off putting these VOCs was unknown. The presenter at the OPHIcan be

contacted at chasen.graley@dot.ohio.gov

I hope this can be of some interest.

I have reviewed the site cleanup proposal prepared by the Vernay contactor. In addition to my comments published in the article above, I have additional observations below:

The residents of YS should insist that site cleanup proposal (CMP, June 2019) be modified as suggested below:

(1) Deeper sediments underneath former Plant 3 (to 60+ ft) should be excavated out in order to remove the contaminant source (PCE, etc.) as much as possible. If the source is too deep for excavation, suitable reagents should be injected into subsurface to cover the entire “source zone” to destroy contaminants in situ.

(2) The contaminated soil present at shallow depths over a much larger area within and in the proximity of the Vernay lab property boundary should be removed or treated.

(3) The “pump-and-treat” approach of site clean-up which has been in operation for many years is not showing effectiveness. This technique is no longer used for site remediation. However, pump-and-treat can be combined with established approaches for the in situ destruction of contaminated groundwater plume.

The plume can be treated by the injection of suitable amendments into the contaminated aquifer, which should stimulate native bacteria and be much more effective in reducing cleanup time. In situ bioremediation (biostimulation) is a well-established technique for site remediation and it has been shown to be a cheaper and preferred approach at thousands of sites in the US.

Professor Abinash Agrawal,

Wright State University

Oct 19, 2019