Vesper Energy is planning to build a 175-megawatt solar photovoltaic array on close to 1,300 acres of farmland spanning Miami, Cedarville and Xenia townships. (Photo by Megan Bachman)

Utility-scale solar project moves ahead

- Published: December 16, 2020

A utility-scale solar project southeast of Yellow Springs is moving forward, and so is a grassroots effort to stop it.

Vesper Energy is planning to build a 175-megawatt solar photovoltaic array on close to 1,300 acres of farmland spanning Miami, Cedarville and Xenia townships. The Houston, Texas, company hopes to apply for a state permit for its Kingwood solar project in the spring and start producing green electricity in a few years.

But a group of neighbors opposes the project for aesthetic, environmental and economic reasons. Members of the group Citizens for Greene Acres say they want to preserve the rural nature of the area and worry about negative impacts to wildlife, water resources and farmer incomes if it’s built.

On a Zoom video conference organized by Vesper on Oct. 26, project development manager John Soininen shared more details about the company’s plans. He was met with questions on issues ranging from the impact on property values to plans for managing weeds.

After two years of acquiring land leases in the area, a total of 1,275 acres are now leased, Soininen reported at the meeting, and the company is moving ahead with environmental and electricity resource studies.

The leases are for 43 years and start at $1,000 per acre per year, according to past News reporting. Farmland typically rents for between $200 to $250 per acre in the area.

At the meeting, Soininen defended the rights of the landowners who signed the leases, adding that the company plans to work with neighbors to address their concerns.

“Landowners do have rights,” he said. “The land owners from whom we leased property do want to do this project. It’s our job to mitigate any impacts from the facility.”

Asked at the meeting if he, personally, would want to live next to a utility-sized solar array “eyesore,” Soininen said he would, adding that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.”

“I don’t view it as an eyesore, I view it as progress,” he said. “I would much rather view a renewable energy facility than a smokestack.”

Neighbors have raised a variety of concerns about the project, some of which were posted in the Zoom chat box.

To Nicole Marvin, of Citizens for Greene Acres and a neighbor of the proposed project, the principal concern is that the project would put valuable agricultural land out of production, she said in a later interview. The group’s members are not against solar energy, they just would prefer it on “brownfields” and on rooftops, not prime farmland.

“We have really valuable agricultural land,” she said. “If they want to do solar projects, that’s great. We just want responsible siting.”

At stake is the rural nature of the area, which will more closely resemble an industrial power plant, Marvin said. And with that, farmers will have less land on which to produce food, and generate an income.

“The impact economically on the agricultural community is substantial,” Marvin said. “It would be pretty devastating.”

Although no participants in the meeting expressed support for the project, the News has previously spoken with some area neighbors who are supportive. They say that lease payments will be able to help area property owners, some of whom are farmers, supplement their income and prevent other types of development, such as residential.

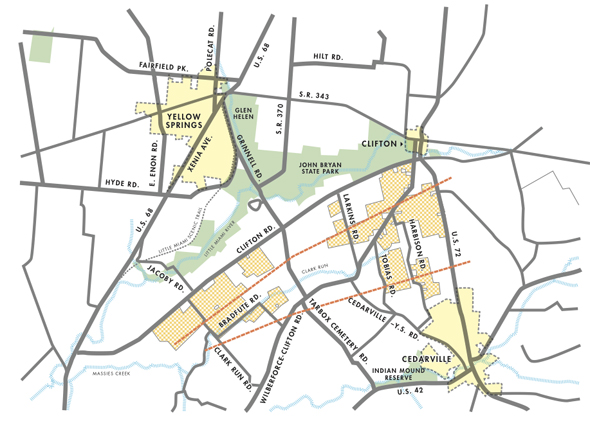

The proposed solar project would be located between Yellow Springs and Cedarville, on properties south of Clifton Road, west of State Route 72 and on both sides of Wilberforce-Clifton Road. Some sections of the array would be across Clifton Road from the Glen Helen Nature Preserve, John Bryan State Park and Clifton Gorge.

Compared to the two solar arrays in the village — one-megawatt arrays at Antioch College and on the Village-owned Glass Farm — Vesper’s utility-scale array would be about 175 times larger.

Soininen, who lives in Ipswich, Mass., started on the project in January after a different company representative acquired leases in the area beginning in 2018.

The project was started by Lendlease, an Australia-based international urban developer. Lendlease’s renewable energy division has since been spun off as Vesper Energy, a private equity-funded company, Soininen explained at the meeting.

Land leases have been acquired by a Texas alternative energy company for a utility-scale solar array on close to 1,300 acres of farmland in Greene County just southeast of Yellow Springs. The 43-year leases are clustered in two areas between the village and Cedarville, near a high voltage power line. The 175-megawatt array would be south of Clifton Road, west of State Route 72 and on both sides of Wilberforce-Clifton Road south of Clifton. The company, Vesper Energy, is planning to apply for a state permit in the spring, while some neighbors continue to oppose the project. (Map data from Vesper Energy)

Why solar? Why Ohio?

Soininen began his presentation by explaining why utility-scale solar is coming to Ohio.

Solar projects are particularly attractive to locate in Ohio, Soininen explained, because it is part of the East Coast utility market, the country’s largest, giving firms more customers to which to sell their green electricity.

“It’s a very large energy market with a lot of demand,” he said.

Since 86% of Fortune 500 companies have published “sustainability goals,” many are looking to offset their power consumption with green energy purchases, Soininen added. In fact, Vesper is in the “late stages” of negotiating with a single corporation that would buy the output of the entire solar project, he said at the meeting.

That comment drew criticism from one participant in the Zoom meeting, who asked how the project would benefit the area if the power was sold to the East Coast.

Participants questioned the location on “productive farmland” rather than “non-agricultural land like landfills, brownfields.”

“Why not build directly adjacent to an interstate?” another asked.

Simply put, it’s cheaper to put solar panels in fields rather than on rooftops or brownfields, Soininen said in a later interview. It costs five times as much to install panels on rooftops than in greenfields, he added.

“We need to achieve economies of scale,” he said. “It’s a lot harder to send someone up on your roof than to put one million panels in a field.”

Asked to elaborate on why the area was chosen in a later interview, Soininen pointed to its proximity to high volume electric transmission lines, willing landowners and “a lot of open space.” All three make the project economically viable, he said.

“Why are we here? Because there is a ‘superhighway ’ — there are existing transmission lines,” he said. “The infrastructure exists. It’s that simple.”

Two major interconnection lines run through the project area, part of the 138kV Clark-Greene line, which is considered a “high voltage” line. The project’s size is determined by the amount of electricity the lines can carry, Soininen explained in the interview.

Utility-scale solar is relatively new to Ohio, but the projects are coming, Soininen said at the meeting.

“Ohio has a lot of flat, tillable acreage that makes it desirable for solar energy generation,” he said.

At present, there is no operating solar array in Ohio as large as Kingwood would be. Two southern Ohio projects, at 200 and 300 megawatts, are currently under development.

Asked whether the company had completed any similarly sized projects, Soininen said that the company’s largest operating solar array, in California, was 60 megawatts, one third of the size of Kingwood.

But utility solar development is moving quickly here as the price of solar panels has plummeted in recent years. In total, Soininen said, there are 13,000 megawatts “in the pipeline” to be developed in Ohio.

“The practical reality is that the cost of solar has reduced approximately 80% in the last decade so that solar is competitive with most forms of fossil fuels,” Soininen said.

For instance, during 2010, just over 1,200 gigawatt hours of utility solar were installed in Ohio, while in 2019 the figure was 72,000 Gwh, or 60 times more, according to the U.S. Energy Information Agency.

The shift away from fossil fuels for environmental and climate reasons is also driving the change. However, even though Ohio has gutted its renewable energy mandates, the project is still viable here because of Ohio’s connection to the East Coast. The lack of strong state renewable energy benchmarks won’t affect the project, Soininen said in an interview.

“We’re here and we’re doing this because there is a huge demand for clean energy, and solar is more effective than nuclear, gas and coal,” he said.

Solar permitting process

Pivoting to the local project, Soininen explained the process for receiving a permit through the Ohio Power Siting Board, or OPSB, a division of the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio.

Earlier this year, Vesper received its permit from the agency for a 610-acre, 80-megawatt Nestlewood solar project in Brown and Clermont counties, east of Cincinnati. The process involved one year of initial studies and one year of meetings and hearings with the agency, Soininen said.

For the Kingwood Project, the company must submit project plans and maps, interconnection studies, an economic impact study, an acoustical assessment, wetland maps, a landscaping plan, a decommissioning plan, and more, according to a PowerPoint slide on the process.

Soininen called the permitting process “robust and complex,” involving multiple state agencies, including the state Historical Preservation Office, the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency and Ohio Department of Natural Resources.

“Every agency that exists gets a voice in this process,” Soininen said in the interview. “How does it get more robust than that?”

By contrast, he added, “I can go to Texas and get a permit for a 500-megawatt solar project in a week.”

But some neighbors have been critical of the process, which they say circumvents local governing bodies.

“One of the biggest concerns is that these projects keep getting permitted and changing the landscape of the rural community, yet we have no voice,” Marvin, the neighbor, said.

The Ohio Power Siting Board approved seven projects totaling 1,775 megawatts in the last two years, and listed no applications as having been denied.

Although they don’t have the ability to keep a utility-scale solar project out of their area through zoning, local officials do have a role in the OPSB process. Local officials can register as “interveners” in the process, which gives them the ability to present testimony at public hearings, apply for a rehearing or appeal the board’s decision. But they have to get involved at the start of the permitting process to participate.

Citizens for Greene Acres are currently asking local government officials to do just that. In October, they sought support at a Miami Township Trustees meeting, and are making plans to set up a working session with Greene County Commissioners. To participate, government bodies must involve their legal counsel.

“We don’t have a say at the local level,” Marvin said, “but we expect our township trustees and commissioners to get involved in the project.”

Citizens for Greene Acres as an organization is also planning to intervene in the process.

The company hopes to begin its application process in the spring of 2021. At present, the company is undertaking preliminary engineering assessments and inspecting for cultural artifacts in the area.

“They are literally looking for arrowheads across the entire site,” Soininen said of the current activity on the site.

Solar project details

Soininen went on to offer details about the proposed solar facility, which includes more than just solar panels. Also making up the facility are inverters, transformers and substations, along with access drives and fences.

In response to questions about the number and location of the electric substations and other industrial infrastructure, Soininen said that those details had not yet been determined.

The solar panels themselves will be about four-and-a-half feet tall. Inverter stations will be a little under nine feet, and perimeter fences — set to circumvent each array — will be eight feet high and either a chain-link fence or a “farm fence,” according to a Powerpoint slide.

Although no figure was provided for the number of panels that will be part of the array, using comparable figures for Vesper’s Nestlewood project, an estimated 828,000 panels will be installed in the Kingwood project.

The array will be surrounded, in part, by “pollinator-friendly plantings,” Soininen added, which he suggested may actually have a beneficial impact on the area wildlife.

With pollinator-friendly species, he said, there is a 65% increase in the amount of carbon sequestered from land at the site, along with a three-fold increase in the amount of food for pollinators.

“It’s certainly a change in the landscape, but there are a number of reasons why that change should not be causing significant alarm,” Soininen said.

Later in the process, the company will also meet with adjacent landowners to plant “vegetative screening” along the panels.

Soininen briefly described the construction process, saying that steel piles are driven into the ground every 20 feet. The company uses sonar to search for field tiles prior to the installation and would repair any that break, he added. In general, they try not to dig unnecessarily.

“We’re trying not to disturb the site and create opportunities for erosion and sediment runoff,” he said.

Finally, Soininen emphasized the economic benefits of the array, through a PILOT, or payment in-lieu of taxes, agreement, a form of reduced tax payments. Under that program, local government entities would receive annual tax payments of $1.575 million for the life of the project. An estimated 300 temporary construction jobs would be created, along with five permanent jobs, Soininen added.

Another economic benefit, according to Soininen, is that property owners can diversify their income, which reduces residential or commercial development pressure in the area.

Citizens for Greene Acres has their own figures that show that the loss of farmland could be “devastating” to the local farming community, according to Marvin. Those figures have yet to be released. Farm revenues, Marvin added, “stay in the community,” compared to money made by Vesper.

Other questions

Soininen fielded a variety of questions from participants during the meeting, submitted in the chat box. One of the first questions to be raised was on the issue of property values, with some neighbors concerned their properties will be worth less once the solar project is built.

One questioner said that they believe values may drop as much as 40%. Soininen replied that he has never read a peer-reviewed study that showed “anywhere close to that.” Instead, a decline of 2–4% was more likely, he said.

“Are you saying that we as neighbors should have to bear that 2–4% decrease in property values?” a commenter added in the chat box.

Later, a spokesperson for the Kingswood Solar Project contacted the News by email and clarified that the company does not project a decline in property values, pointing to some studies that have shown that property values may increase.

Asked about the impact of severe weather on the panels, Soininen said that sensors will turn the arrays away from an incoming hail storm. With tornadoes, though, “all bets are off,” he said.

In response to a question about the potential contamination of private water wells from the project, Soininen said, “I can’t guarantee that your well won’t be contaminated, but I can guarantee that your well won’t be contaminated by our project.”

Because of the project’s official name of Kingwood I, one participant asked if the company was planning a Kingwood II. Soininen responded in the negative.

“Will [Greene County] residents benefit from the solar energy?” another asked.

Soininen said that the energy will be purchased by a third party but that, technically, the electricity produced will flow into nearby homes.

“The reality is, this clean energy is supporting the regional electrical infrastructure,” he said.

Citizens for Greene Acres later compiled a list of 40 questions that were either unanswered or they felt were not answered sufficiently during the meeting, which they shared with the News. Questions included how far noise-generating equipment would be from local homes, whether solar panels would create runoff and release heavy metals, how fencing would impact wildlife habitat, whether “heat islands” and visual glare would be created by the array, how the panels would be decommissioned and dismantled, and more.

One Response to “Utility-scale solar project moves ahead”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

NIMBY:It’s not just for the suburbs anymore.