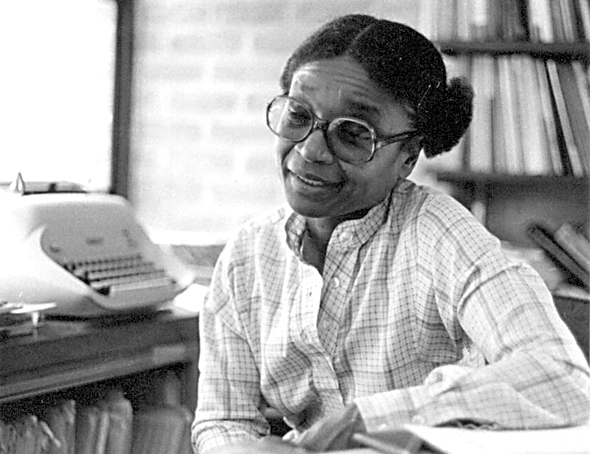

Jewel Graham was a much-loved professor of sociology at Antioch College for many years and was deeply involved in supporting the Black students in the Antioch program for interracial education during turbulent times. Also the second Black woman to serve as president of the World YWCA, Graham was named to the Ohio Women’s Hall of Fame in 2008. (Photo Courtesy of Antiochiana, Antioch College)

‘Loud As the Rolling Sea’ | An interview with activist, educator Jewel Graham

- Published: January 23, 2022

In 2014, “Loud as the Rolling Sea” host Kevin McGruder spent a warm summer afternoon talking to Jewel Graham in a wide-ranging oral history interview that covered pretty much her whole life.

Graham, who died in 2015, was a much-loved faculty member at Antioch College for many years and was deeply involved in supporting the Black students in the Antioch program for interracial education during turbulent times. This portion of McGruder’s interview with Graham covers her life growing up in segregated Springfield, Ohio, and the challenging social justice work she did for the YWCA, both stateside and overseas.

The transcript is edited lightly for length and clarity.

Jewel Graham: My full name is Precious Jewel Freeman Graham. Freeman’s my maiden name. Graham is my husband’s name, and the rest is my name.

Kevin McGruder: And we’re at your home on Corry Street in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Where were you born?

Graham: I was born in Springfield.

McGruder: What was Springfield like when you were growing up?

Graham: Springfield was a thriving community when I was growing up. It was a manufacturing center. It was on [highway] 40 and the trains came in and there was lots of manufacturing. It was fairly open to Black men in the sense that it was hiring Black men in manufacturing jobs before a lot of other places were. It was a segregated community, except the schools were not segregated, schools were integrated. All of us went to the same schools. But all in all, it was a pleasant place. I mean, it wasn’t unpleasant, you know.

McGruder: You had mentioned earlier that your parents moved from Georgia. What were their names and why did they move?

Graham: My father was Robert Lee Freeman, and my mother was Lula Belle Malone Freeman. They migrated to Ohio from Georgia around 1920. My father came from a farm background, my mother’s people were tenant farmers.

McGruder: And with the school system, you said they were not segregated. What was your school life like?

Graham: My school life was . . . I had a dual school life. I went to school with white children, and we were friends in school. You know, we got along very well, and there were some who lived not too far from me. And we walked home together and that was the end. It’s interesting because when I go to high school reunions, the white people have an entirely different memory of what it was like. They don’t remember how segregated it was and how the Black kids just did not participate in school activities, except a few of us who didn’t understand that it was not meant for us. And we would show up anyway for the Latin Club and the French Club and the Drama Club and so on.

McGruder: And were you able to participate when you did show up?

Graham: Well, you know, high school clubs I was in. . . we did “Robinson Crusoe.” I have pictures of me and the other Black students who participated and stuff like that. But we had a very active high school life outside of the school. It was at the YMCA and the YWCA. And we had social activities and we had service activities and we had all kinds of things.

McGruder: And these were segregated?

Graham: That was the Center Street branch of the YMCA and the Clark Street branch of the YWCA. And interestingly enough, those club pictures went into the yearbook as school activities. But they didn’t have anything to do with it.

I was a very good student. And when the guidance counselors and teachers were talking about college, I assumed that they were talking to me, too, like they were talking to other kids who had done well in school. And so I was planning to go, thinking probably I would go to Ohio State. I wasn’t really happy about it because at the time, Ohio State didn’t allow Black students to live in the dormitories on campus. They had to find places in town. While I was thinking about what I would do, a neighbor, Ernestine Lucas, lived across the street from us who was a [graduate of historically Black college] Fisk [University], asked me to come over and talk to a Fisk recruiter who was coming, so I did that. They offered me a scholarship and I accepted the scholarship and went to Fisk.

McGruder: So what was Fisk like? That would have been in the early ’40s.

Graham: I graduated from high school in ‘42. I was at Fisk from 1942 to 1946. I remind you that was during the war. It was essentially a women’s college. There were a few men, not very many, which meant that the women had to take the leadership positions on campus and they had to, you know, it was good. Fisk was good for me.

McGruder: What did you study?

Graham: I majored in sociology and minored in psychology. And don’t ask me why, because that was a time when if you were a Black woman, you were going to go and teach. That was it. And if you were an educated Black woman, you would teach. If you didn’t get an education, you’d do hair. Or if you were talented, you might end up in a nightclub singing or something. But those were the options. I took sociology because I was interested in it and psychology. I worked for a couple of summers at Fisk at the Fisk Race Relations Institute, which was famous at the time and still a pretty respected, I think, organization. There are many wonderful things about Fisk that I remember.

The YWCA was hiring, had a very extensive hiring program, a lot of women got started in the YWCA. It was probably one of the very few places where women, white and Black, could get administrative, executive experience and planning experience. Anyway, I found a job in Grand Rapids, Mich. And the thing is, though, the YWCA was one of the few organizations in the South, they were pioneers in a lot of ways with Black people and Black issues and social justice issues. And the whole idea was it was trying to integrate its program and its staff. They wanted to include Black women. And they set up branches in order to serve Black women. But now they want to abolish branches, totally abolish branches and bring everybody under one roof. So I went as a program director, teenage program director to the YMCA, Grand Rapids, and I worked there for three years.

McGruder: And that’s late ’40s.

Graham: It would be in the ’40s. But Grand Rapids was a good experience for me. Now, this is another interesting thing, though. The president, I think she was president at the time of the YWCA. She was either president or chairperson of the board was Helen Wilkins Claytor. Her son is Roger Wilkins, and she had worked for the YWCA for a long time, the national YWCA and she married a person in Grand Rapids and stayed there and was active in the YWCA. But then Roger was growing up at the same time. And so that was when I began. I had been active in the YMCA earlier in the Clark Street YWCA in Springfield. But I began to get a sense of what the YWCA was really about. It wasn’t just about swimming pools. It had social justice issues that were important.

McGruder: When did you start getting involved with the Worldwide Y?

Graham: Now, that’s the date that I do remember: 1975. I was on the national board already, but then they wanted me to run for the board of the worldwide Y. They called it the executive committee. And so I did that and I was elected.

McGruder: And about how many people were on that board?

Graham: There were 20 on the executive committee. And we met in Geneva every year. And it was a working board. So we had responsibilities. I did workshops in Botswana and I’d go to conferences in Chile and, you know, different places — go to visit the Ys of China. And that was another pivotal experience in my life. The whole business with the worldwide Y. You know, I just saw all the women all over the world working on the same kinds of things just in different environments. And they had the same concerns. And they were wonderful.

“Loud as the Rolling Sea” is produced at the Eichelberger Center for Community Voices at WYSO and hosted by Kevin McGruder. This story was edited with help from community producer Amy Harper.

Funding for this project comes from The Yellow Springs Community Foundation, the Yellow Springs Brewery and from Rick and Chris Kristensen, Re/Max Victory and affiliates in Yellow Springs.

One Response to “‘Loud As the Rolling Sea’ | An interview with activist, educator Jewel Graham”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

Hello, I spent most of my time at Antioch 1967-1972 in the history, art, philosophy, and earth and biological science departments. Plus dance classes for gym requirements. I didn’t see the relevance of the Civil Rights Movement to my own personal struggles. Too bad I didn’t have the wisdom and foresight to take a class from Jewel Graham. Thank you for republishing this interview. It took years for me to get it that there was the white male supremacy network/game/structure and then — there were the rest of us.