Book examines college readiness

- Published: May 21, 2022

In her time spent as an educator and researcher at historically Black institution Central State University, villager and writer Barbara Fleming, Ph.D., noticed a trend that troubled her: Black students appeared to have been less prepared to enter college by the school districts that served them, making them less likely to complete their postsecondary education. Further troubling was the great debt these students incurred in paying for their college education, whether they went on to obtain a degree or not.

These observations — accompanied by a wealth of supporting data — form the nucleus of Fleming’s latest work, “Desperately Searching for Higher Education Among the Ruins of the Great Society.”

The work comprises two volumes; the first was published in November, with the second to debut this month. The volumes are published by Silver Maple Publications, a small press operated by Fleming and her husband, John E. Fleming, Ph.D.

Barbara Fleming spoke to the News last month about her two-year research and writing process and her intentions for the work, which she said she hopes will be a reference text for educators and community leaders.

“I wrote it so [they] would have a source that they could go to to find out what’s going on with Black education,” she said.

Fleming, an Alabama native who has a doctorate in developmental psychology, is also a fiction writer and playwright, with several works published by Silver Maple. “Desperately Searching,” however, is the first large-scale academic text she’s released via her press.

Fleming said the work was spurred by the several years she spent as the director of planning and institutional research at Central State.

“I wrote a five-year strategic plan [while in that position] that covered some of the same topics addressed [in the books] with respect to the impact of poverty in the home and community on the lack of academic readiness of Black students — especially students from large urban cities in the U.S.,” she said.

The two volumes of “Desperately Searching” are large and comprehensive, Fleming said, adding that the work was “not written to be read all at once.” Instead, each of the volumes’ chapters shines a light on a different aspect of or subject within its unifying theme, and they were written so that they could be read independently from the rest of the work.

“That way, you can look at the issues you’re interested in,” Fleming said.

In the book’s chapter on methodology, in which Fleming lays out her research methods and how data is presented, she writes that her original intent was for the book to be contained in one volume. Fleming made the decision to publish the work in two volumes in order to “do justice to the topics and issues that are discussed.”

She also writes that, because “people process information differently,” much of the information included in each chapter is presented in both explanatory texts and in tables.

The first volume of “Desperately Searching” focuses primarily on elementary through high school students, with much of the data encompassing test scores along socioeconomic divides.

Fleming’s methodology chapter states that, in order to simplify her analysis, she confined her research to Black, white, Asian-American and nonresident students.

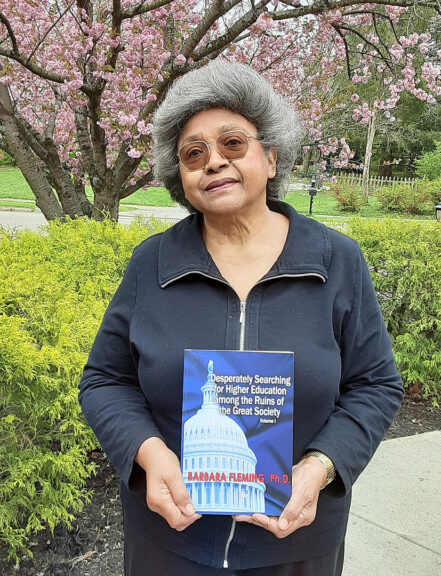

Villager and writer Barbara Fleming with the first volume of her recently released book. (Photo by Cheryl Durgans)

Fleming captured the data for the first volume primarily by studying several years of figures from two international tests, the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMMS) test and the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) test, and from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP).

The book also includes chapters giving background information on Black, single-parent households and the U.S. welfare system; household income and child poverty; and urban charter schools.

Through the data, Fleming aims to make the case that many students — especially Black students — in low-income urban and rural school districts are not having their educational needs met.

“These students have the lowest scores of any racial-ethnic group in the country … but it’s all part of the system of poor education that these kids get in this country,” she said. “We have, essentially, two education systems in America — one system for the affluent upper and middle class and one for poor urban and rural families.”

Fleming said the second volume will zero in on the unique experience of Black college students in terms of matriculation, completion of degrees and student loan debt.

She emphasized that education has always held “pride of place” in the Black community, but that, according to a 2019 study, the median annual income for Black families is around $40,000. For this reason, she said, Black college students often must rely on student loans or other financial aid in order to attend college.

“That’s not a trivial thing — to [take out a loan] when you don’t understand the implications of defaulting on that loan and what that could mean for your life,” she said.

Fleming described a cyclical effect: low-income Black students receive subpar primary and secondary education and are thus underprepared for college, which they’ve financed with large personal loans; and, according to her research, are more likely to drop out of college than their white counterparts — but are still on the hook to pay for their student loan debt.

“There’s no question that one of the things that contributes to the low income level of Black people in this country is the fact that they’ve got this debt hanging over their heads,” she said. “That’s the thing that bothers me more than anything else — for an 18-year-old to get an unsecured loan without really understanding what it means.”

Fleming said that, in her view, the easiest way to address the debt carried by young Black Americans is to institute some loan forgiveness — or craft a system of postsecondary education where that debt doesn’t exist.

“President Obama has said he thinks the first two years of community college should be free, and I agree,” she said. “The government really does need to figure out a way to get people out from under [the burden of debt] because it’s sinking the economy — nobody is dealing with this intelligently.”

In the long-run, though, Fleming said the best course of action is for the federal and state governments to invest in low-income school districts. Understanding that more resources are needed to do so, she suggested a simple solution: Divert money away from prisons and into schools.

“We spend so much money on incarcerating people for drug offenses. It costs a lot of money to keep somebody in prison,” she said. “We can spend that money on schools.”

She added that this method would have the advantage of not diverting revenue away from school districts that are already adequately funded.

“You don’t have to take it from the suburban schools and institutions,” she said. “Let them keep everything they have — because they’re not going to give it up anyway.”

“Desperately Searching for Higher Education Among the Ruins of the Great Society,” Vol. I, is available now at silvermaplepublications.com. Vol. II is set to be released later this month.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.