Longtime village resident Sue Parker, 84, relaxed on her Thistle Creek porch one sunny summer evening, and thumbed through her impressive collection of postcards. Here, she holds up one showing the seminary school she attended in Chicago. (Photo by Reilly Dixon)

Elder Stories | Sue Parker, always the good neighbor

- Published: July 28, 2025

ELDER STORIES

A series of occasional articles exploring the lives and contributions of villagers 80 years of age and older. If you’d like to suggest a person for the News to consider for this series, email ysnews@ysnews.com.

Since coming to Yellow Springs in 1970, Sue Parker has lived in 12 different homes throughout the village.

It may not be a town record, but she wagers it must be close.

From Parker’s decades of bopping around town, there’s hardly a square block she doesn’t know intimately well — she’s been a neighbor to many. At 84 years old, Parker can recall with pristine clarity who owned what home from years ago, what flowers grew around their porches and what the children playing in the backyards grew up to be.

For Parker, neighborliness is a virtue — one that extends well beyond her quiet Thistle Creek cul-de-sac, and into the intricate web of local connections she’s woven since landing in Yellow Springs.

She’s been involved in a handful of village mutual aid and advocacy groups, and all the while, she has been a champion for those on the margins, both near and far.

“Throughout my life, I’ve often found myself thinking of that one Anne Frank quote,” Parker told the News from her sunny living room last month.

“‘In spite of everything, I believe that people are really good at heart,’” Parker said, citing the famed diarist. “So, I’ve always tried to appeal to people’s kindness. I think even the cruelest of us can change our minds.”

A minister’s daughter

Parker — née Turnbull — was born in 1940 in Springfield, Massachusetts as the middle of three daughters to a progressive pair of parents.

Her mother, having grown up in Egypt, was worldly and empathetic. Her father was a United Presbyterian minister, whose profession relocated the Turnbulls from the Atlantic coast a few times: first to Latrobe, Pennsylvania, and later to Cleveland, where Parker would come of age as the self-declared “rebel” of the family.

“But of course, that’s all relative,” she said with a laugh. “I’m sure people thought we were big rule followers. But there was one time I squirted my drama teacher with a squirt gun. Can you imagine that happening today?”

Parker enrolled in the nearby Muskingum College in 1958 and three years in, the Civil Rights Movement of the ‘60s would strike sparks in Parker’s heart, igniting a lifelong passion for social justice.

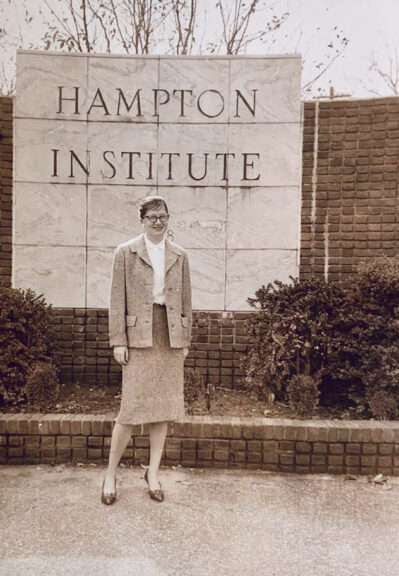

In 1961, Parker entered into an exchange program that allowed her to trade places with a student from the Hampton Institute.

In 1961, Parker entered into an exchange program that allowed her to trade places with a student from the Hampton Institute. (Submitted photo)

After taking a train from Cleveland to Virginia, Parker, at 20 years old, became the only white woman student on the campus of the historically Black college, giving her what she refers to as “the best education [she’d] ever had.”

“Even though it was just for a semester, it still felt like a really long time,” she said. “It truly changed my life.”

While at Hampton, Parker took myriad African American history and literature courses, she sang in the chorus and learned playwriting from the famed writer Jay Saunders Redding.

She also got in with a crowd of Unitarians who were pushing to desegregate the nearby Woolworth’s lunch counter. There, she and her friends would picket the restaurant — holding signs with messages like “It’s Sure No Lie You’re a Jerk, If You Can’t Buy Where You Work” — and on occasion, she and her Black friends would sit at the counter, simply looking to buy a milkshake, only to get kicked out of the segregated joint.

“It was an outrage to me,” Parker said. “But still very frightening — I didn’t know what was going to happen, if we’d get arrested or not.”

She added: “But there was never any question. I was entirely motivated to do what we were doing.”

Parker attributed the origins of her conviction to her mother, whose childhood in Egypt opened her eyes to the diversity in the world. According to Parker, her mother would regularly have folks from other countries over for dinner when they lived in Cleveland — hoping to instill the lesson in the Turnbull girls that, simply, “the world isn’t white.”

After Parker’s semester at Hampton — and with the counters, the pews in the Presbyterian churches, the movie theaters and more all still segregated — she returned home to finish her sociology degree in 1962.

Down and out in Chi-town

After graduating, she turned her eyes to the newly established Peace Corps. A telegram from Sargent Shriver, who was the driving force behind the creation of the program during the Kennedy administration, said she had gotten in.

“It was pretty cool,” Parker said with a grin. “I still have that telegram.”

An injured back waylaid her plans of going to the Philippines — though she still picked up a little Tagalog — and instead of the corps, Parker headed to McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago to work on a Master of Social Work degree.

“There are reasons we sometimes get a little off track, aren’t there?” Parker mused.

A few years after arriving in Chicago, and after meeting her first husband — another seminary student and aspiring minister — Parker’s first and only daughter was born in 1966: villager Jennie Gilchrist.

To support baby Jennie, Parker took whatever work she could find — “hundreds of jobs,” according to her — from working at the YMCA hotel, calling out recreation activities over the loudspeaker, to her most stable gig with the Chicago chapter of the National Urban League, interviewing and placing Black job seekers with stable employment in the city.

During her time with the Urban League, Parker and some friends heeded the national call from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to join in the marches for equality in Selma, Alabama, in the spring of 1965. Again, she took a train and headed south.

“We were a part of these unbelievable crowds from all over the country,” she recalled. “I remember how powerful the march was, the chants, the speeches, the feeling of being a part of it all. But I also remember the jeers and ugly signs and insults. It’s always shocking to see white people get so evil at people doing something good.”

Upon Parker’s return to Chicago, the Urban League laid her off for having gone to Selma. To make matters worse, Parker and her husband’s marriage folded, and life in Chicago got even more rough for her and Jennie.

“Being a single parent anywhere is really, really difficult,” Parker said. “Working, supporting yourself and taking care of a child just can’t be done — especially in the city.”

Living in the south side of Chicago in the late ‘60s, Parker tried splitting childcare with neighboring mothers, but eventually, she’d had enough: She wanted out. Parker began putting classifieds in “Mother Earth News,” seeking a more communal, family-friendly way of living anywhere else.

“I wanted open air, shared childcare,” Parker said.

Longtime villager, writer and counselor Maxine Skuba — a friend of Parker’s — had recently moved to Yellow Springs and wrote to Parker: This was the place to be. A perfect commune.

Settling in the village

When Parker and Jennie landed in Yellow Springs in 1970, she immediately got wrapped up in the small-town social fabric.

It was a time when Antioch College was in its heyday, and scores of intellectuals, eccentrics, artists and young families overran the village. Parker fit right in.

One of the first places she stayed was a home she was housesitting on Fairfield Pike. There were 22 cats who needed to be taken care of while the homeowners went to and from California, funnily enough, looking for their own commune.

“So, that was my intro to Yellow Springs — me and 22 cats,” Parker laughed. “And I don’t even like cats. I’m not sure they were all there when the couple came back. Who knows. Maybe there were more.”

Parker’s hopes of getting relief in raising Jennie as a single parent were met in her new village, she said. Very soon after moving, she began cooperating with other parents to split custody and responsibilities.

“I’ll take yours and mine for a little while, and later on, you’ll take mine and yours. Then you’ll have your time, and I’ll have mine,” Parker said. “There really was a time when people thought I had three kids!”

For a brief amount of time, Parker fell into YS Friends Meeting — the local Quaker gathering at Rockford Chapel — where she met some of her most influential village friends, including Peg Champney and Hazel Tulecke. Out of Friends Meeting spun a co-counseling program, which Parker described as “peer counseling” — a chance to “vent, cry and scream” with a trusted person.

“I had this horrible marriage behind me, and Hazel really led me through that,” Parker said.

With some time, she was led to meet the love of her life.

On a fateful night at Com’s Tavern on West Davis Street — a popular neighborhood restaurant and bar that’s now a private residence — Anna Hogarty introduced Sue to Bob Parker. The rest was history.

Not long after their romance began, Parker joined her husband in Antioch College’s department of cooperative education — sending students to far-flung places whole semesters at a time.

The Parkers married in 1982 in a Northwood Drive home they were housesitting for the Erskine family. Parker said it was a cheap wedding — “Not even in the backyard!” — in the home’s living room and kitchen. Parker said they surprised their guests who were over that evening for a Shakespeare reading group.

After working at Antioch and getting her master’s degree in counseling from Kent State, Parker’s career continued down the well-trodden path of working for others.

Over the years, she would work in the Greene County Refugee Resettlement Program, at the circulation desks of several county libraries, the YS Community Children’s Center, and for a whole decade, at the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center in Wilberforce.

All the while, Parker had her fingers in a number of local organizations and grassroots efforts.

As a lifelong proponent of affordable housing, she attended regular meetings at Bev Viemeister’s home in the late ’80s and early ’90s — before the creation of YS Home, Inc. — about how to create more long-term affordable housing options in the village.

“This was a time when affordable housing was considered controversial,” Parker said. “But it was very personal to me. I had so much trouble finding a reliable home when I first got here. I was always counting on the kindness of strangers.”

She added it’s still personal to this day. She deeply respects the work of Home, Inc. and remains a stalwart advocate for building more safe and affordable homes in Yellow Springs.

Founded in 1980, the Feminist Health Fund raises money from the community and disperses it to needy women suffering from a catastrophic illness. Board members from 2015 were, clockwise from front, Esther Hetzler, Kathy Robertson, Sue Parker, Janet Ward, Joyce Morrissey, Denise Cupps and Marianne Whelchel. Not pictured is Elizabeth Danowski. (News archive photo by Megan Bachman)

Parker was also one of the early organizers of the local Feminist Health Fund, which was founded in 1980 to provide financial assistance for healthcare needs of area women. At the time, the fund was an “ad hoc group of women,” just looking to cut checks to any local woman in need — no questions asked, Parker said.

She was also helpful in the establishment of the Women’s Park along the bike path on Corry Street; Parker proofread the tiles submitted for the walkway, as well as copyedited an accompanying publication, “Celebrating Women, the Women’s Park of Yellow Springs.”

Later, in 1999, the Parkers were among the scores of villagers concerned about the potential development of the 940-acre Whitehall Farm. She and others held a flea market at First Presbyterian Church to raise money to help the proto-Tecumseh Land Trust initiative to permanently preserve the farm — an effort that was successful.

“We made over $7,000 in a day and a half from that market!” Parker said. “In all my years here, it was the only thing I’ve ever seen people agree on.”

When she and Bob weren’t pressing their noses to the civil grindstone, they were often on the boards of Center Stage — Bob would often get the lead, Parker said, and she’d be singing her heart out in the chorus. She said they made it through all the Gilbert and Sullivans.

(Photo by Reilly Dixon)

A good neighbor, still

Now at 84, Parker’s life has slowed to a quiet, more comfortable pace.

Bob passed away peacefully a few years ago, with Parker by his side. Still, family, friends and neighbors keep her entryway a regular revolving door. She said she loves it.

Though Parker’s not as directly involved in the small-town comings and goings as she was, she still keeps her finger on the local pulse. She watches every school board and Village Council meeting — calling it “good entertainment for us old people” — and loves getting out for a good downtown parade.

Her friend Rob from the YS Bakery comes by with empanadas every now and again, and they’ll chat about the local drama, and a few days a week, Amy Ray comes by with soup and a few good stories.

Though Yellow Springs has grown and changed somewhat since Parker’s first feline-based introduction to town over half a century ago, things still feel mostly the same, she said; people are still squabbling over housing, getting in each other’s business and surprising her with their creativity.

Of the 12 village homes Parker’s lived in, her sunny Thistle Creek home is her favorite. It’s decorated with hand-picked flowers and watercolor paintings — done by local artists — of her previous homes adorn her walls. A hand-signed “thank you” note from Martin Luther King Jr. addressed to her mother sits on a shelf, and her postcard collection runneth over.

To this day, she does what she can to be a good neighbor.

“It’s always been about the people,” Parker said, looking back on it all. “The people are my favorite part of Yellow Springs. The things people have done in their lives here are just incredible.”

She added: “I’m just grateful to have known so many of them.”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.