Hikers carefully navigated the stepping stones across Birch Creek in the Glen Helen Nature Preserve last weekend. The three local rivers that run through the Glen—Birch Creek, Yellow Springs Creek and the Little Miami River—drain runoff from village streets and area farms. Any contamination in the local watershed eventually makes its way into the Glen, impacting ecosystem health and recreational activities. (Photo by Megan Bachman)

Real watershed moments for area

- Published: March 22, 2012

LIQUID ASSETS

This is the third in a series of articles examining issues regarding local water.

• Click here to view all the articles the series

Where Yellow Springs begins and ends is defined by clear political boundaries. But the village also exists within an ecosystem that has boundaries of its own. An important one is its watershed, an area of land that drains into a common waterway.

When someone drives into Yellow Springs from the north on Tecumseh Road (which becomes Polecat), just before passing Jackson Road, the invisible watershed divide is crossed. There are no street signs to mark it and the shift is imperceptible, but the driver has crossed from the Great Miami watershed into the Little Miami watershed, two separate water-drainage systems.

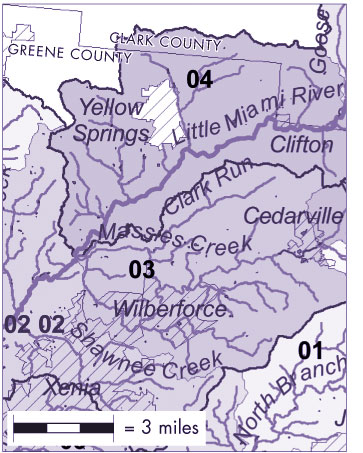

The Little Miami River collects runoff from approximately 1,800 square miles in its watershed. (Map courtesy of Ohio EPA)

Within our watershed, the rain that falls on farm fields, lawns, rooftops and streets, in addition to the water discharged from factories and sewage treatment plants, eventually drains into the Little Miami River, which empties into the Ohio River east of Cincinnati.

Upstream of Yellow Springs in its watershed are potential contaminants that could harm the biological diversity of local waterways and impair overall ecosystem health. Downstream flows Yellow Springs’ own effluent (treated wastewater) and runoff — the town’s contribution to the quality of water in other communities.

In the 19th century, geologist John Wesley Powell described watersheds as places where “all living things are inextricably linked by their common water course and where, as humans settled, simple logic demanded that they become part of a community.”

Today, that common course becomes clear locally when the village’s waterways converge in the Glen. For example, a Subway cup littered on a downtown street is washed into a storm sewer drain in a rainstorm and sent directly to the Glen into what becomes trash-strewn waterfalls, according to Glen Helen Director Nick Boutis. Runoff from paved surfaces and pesticide-treated lawns also enters the Glen, threatening its sensitive habitat. As local ecologist George Bieri put it, “All of Yellow Springs is plumbed to run off into the Glen.”

Since the Glen is part of a larger water system, keeping it healthy requires diligence across the entire watershed, Boutis said.

“The way we protect the Glen is we treat our own backyards like they were part of the Glen,” Boutis said.

Bieri said that understanding the area’s watersheds helps residents appreciate and preserve water resources.

“It’s important to connect with your landscape and realize that everything you do has consequences,” Bieri said. “If you’re not aware, you’re one of the problems.”

While the village’s drinking water is sourced from a deep underground aquifer, not surface water, a discussion of water in Yellow Springs would be incomplete without exploring the streams that snake through farms, forests and streets, harbor aquatic life, and that villagers use for hiking, canoeing and fishing.

What are the boundaries of our watershed and what affects the water quality within it?

Tracing the flow of water

Of the 39 inches of rain that fall, on average, in Greene Country annually, about 10 inches run off directly into bodies of water. Trickling creeks empty into flowing streams that spill into raging rivers. Rain is carried down roof gutters into streets and storm sewers that dump into rivers, all along the way picking up contaminants.

In our watershed, all of the runoff eventually ends up in the Little Miami River. From its headwaters near South Charleston in Clark County, the Little Miami River runs 107 miles south–southwest and drops 689 feet to the Ohio River, draining an area of 1,757 square miles. Near town, it cascades through Clifton Gorge before winding through John Bryan State Park and the South Glen.

Three tributaries capture runoff in Yellow Springs and Miami Township before flowing into the Little Miami River — Yellow Springs Creek, Birch Creek and the Jacoby Branch.

Yellow Springs Creek is the depository for the majority of town, draining 11.5-square miles of mostly urban development. The creek starts northwest of the village, near the Greene County line, and flows 2.5 miles through Whitehall Farm and Dewine Pond and into the Glen Helen Nature Preserve, where it connects with Birch Creek. Birch Creek drains the largely agricultural land northeast of the village, including the Meredith Road area. The Jacoby Branch captures a 6.3-square-mile area of mostly agricultural land southwest of Yellow Springs before emptying into the Little Miami near Jacoby Road.

The northwestern portion of Miami Township drains into Mud Run Creek, which empties in the Mad River and eventually the Great Miami River. The Great Miami River runs through Dayton, Middletown and Hamilton in a separate watershed that empties into the Ohio River west of Cincinnati.

Exceptional water habitat

Whether local surface water is clean or polluted is a matter of perspective. The quality of local surface waters has improved dramatically over the last four decades even while river health is a far cry from its pre-Colombian state.

Early visitors to Yellow Springs would have waded through crystal clear streams teeming with aquatic life and free of many contaminants. Today, our rivers are cloudy with sediment washed from area farms and high in nutrients and bacteria from chemical fertilizers and human and animal wastes. Industrial pollutants accumulate in fish tissues. Rivers race in high rains, eroding streambeds.

But the water quality in several of our local rivers is considered exceptional by the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency based on the condition of its biological communities. Local waterways meet state goals for biological diversity and contain high numbers of rare and endangered species. And they are free of many contaminants from heavy industry, according to Heather Lauer, an EPA spokesperson.

“The Little Miami watershed is known for being a good watershed,” Lauer said. The Little Miami was designated as Ohio’s first National Wild and Scenic River in 1968 and as the state’s first State Scenic River in 1969 because of its value to wildlife and recreation.

Upstream from Yellow Springs are few point-source pollution sites, Lauer added. Wastewater treatment plants in South Charleston, Clifton and Yellow Springs send effluent down the Little Miami before it leaves our area. The other major potential contamination source upstream, according to a 1998 Ohio EPA study, is Ohio Feedlot, a confined animal feeding operation near South Charleston. Ohio Feedlot claims to be the largest indoor cattle feeding facility east of the Mississippi, with 9,800 head of cattle.

Elsewhere in our watershed, and in the Great Miami watershed to the west, pollution is more of a concern, according to Lauer. In the lower Little Miami watershed, Airborne Express in Wilmington sends water laden with glycol, a de-icing agent, into the river, reducing its oxygen levels and hindering aquatic life, according to the 1998 Ohio EPA study. Even worse, in Dick’s Creek in the Great Miami watershed, releases of polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, and other contaminants from an AK Steel factory have made the creek, which runs through Middletown, unsafe for any recreational activity, according to the Ohio EPA.

However, the Little Miami has not suffered from the same poor water quality that the Great Miami has over the years, according Jeff DeShon of the Ohio EPA’s surface water division. And since the 1970 Clean Water Act, water quality has improved statewide, he said, mostly from upgrades to wastewater treatment plants.

In the 1980s only about 20 percent of the Great Miami River met the Ohio EPA’s expectations for biological and aquatic life. By the 1990s, it was at 50 percent. In a 2010 study of the upper Great Miami, it had reached 80 percent, according to DeShon. Quality is even higher in the Little Miami watershed.

“[The Little Miami] received our highest aquatic life designation. It’s been a high quality system. It has a lot of resiliency and it’s staying pretty tough despite the development pressure going on,” DeShon said.

Yellow Springs Creek was meeting its designation as an exceptional warmwater habitat, or EWH, the highest classification possible, in 1998. EWH is reserved for waters that support “unusual and exceptional” assemblages of aquatic organisms, according to the Ohio EPA, and are considered to be state’s best water resources. The EWH designation was also recommended for the Jacoby Branch at that time. In addition, the water quality of the Little Miami River through the Glen was “very good,” though sewer overflows, wastewater toxicity, and urban runoff impaired the biological communities in the lower 20 miles of the river, according to the 1998 report.

Updated data will be released in a new Ohio EPA study in 2013. DeShon expects local river quality to be even higher, as a just-released study of the lower Little Miami showed that 24 of the 25 sites tested on the main stem of the river achieved the state’s highest designation for aquatic life.

Contamination concerns

But surface water quality problems persist. High levels of bacteria impede recreation on rivers. Runoff from farms and urban development has proven harder to mitigate than contamination from wastewater treatment plants and factories. And where streams have been channelized and on farms lacking riparian buffers, water habitats suffer.

Mike Ekberg, manager of water monitoring at the Miami Conservancy District, said that non-point, or distributed pollution not traced to a single polluter, is the greatest concern.

“It’s becoming a realization that it’s all of us. It’s my house, with its roof, and it’s my neighborhood, with its impervious surface area, that contributes to storm water runoff and water quality issues,” he said.

In residential areas, runoff carries lawn chemicals and hydrocarbons from driveways and roads. And when water runs on impervious surfaces rather than infiltrating into soils, it races more quickly to streams, causing erosion. In some places in the Glen, streams have eroded more than one foot in the last decade, according to Bieri.

But local farms may affect water quality more than any source, Lauer said. About 72 percent of the land in Greene County is used for agriculture. The biggest concern, she said, is the soil sediment eroded from farm fields and carried by runoff into rivers. It makes waters run murky, especially during storms, reducing the diversity and populations of aquatic life. At fault are farming practices such as tilling, the use of underground drainage tiles and stream modifications such as channelization. Chemical fertilizers and pesticides and animal manure are also flushed from farms into waterways.

E. coli bacteria were the most significant contaminant of Glen waterways in a recent joint water quality study by students at Antioch College and Wright State University last fall. Seven sites were tested in Yellow Springs Creek, Birch Creek, in the Yellow Spring and near Morris Bean. And while the tests showed that temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen levels were normal, in some locations chloride and nitrate were of concern. Most prominently, bacteria kept the water unsafe for some recreational activities. Similarly, in the recent lower Little Miami study, over one third of the sites failed to meet water quality standards for the recreation due to bacteria.

Swimming in the so-called “blue hole” on Birch Creek might not be advisable and remains officially prohibited, according to Boutis. And though the study found no contaminants or bacteria in the Yellow Spring, Boutis said is it not certified as a drinking source.

On swimming in the Glen’s streams: “The ecology of the Glen is way too fragile,” Boutis said. “You could be disrupting soil, plants and aquatic life. And the Glen is downstream from farms, septic tanks and storm sewers, so you’re swimming in all of that.”

Protecting our ‘blue gold’

Water, which has been called “blue gold” by Canadian environmentalist Maude Barlow, faces threats of depletion and contamination in many watersheds around the world. Water scarcity affects one-fifth of the world’s population, according to the United Nations. In the western high plains of the United States, the massive Ogallala aquifer is being depleted faster than it is being recharged. In some places, water levels have declined more than 100 feet in the aquifer, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

But in the Miami Valley, water continues to flow amply and is getting much cleaner, good news for area residents, according to DeShon.

“It’s a resource becoming more and more in demand as the years go by,” DeShon said. “And it’s something that Ohio has in abundance.”

The buried valley aquifers below the area’s surface waters, which can yield up to 3,000 gallons per minute without depleting aquifer levels, according to Ekberg, are a prime water resource. The underground aquifers provide about 98 percent of the drinking water for Miami Valley residents. But surface waters are important as well, and more communities are beginning to embrace local rivers for recreation.

“Many cities have turned their backs from the [Great Miami] river because it was a waste dump,” said Matt Lindsay, an environmental planner with the Miami Valley Regional Planning Commission. “That recreation angle is helping communities make sure the river stays clean.”

Bieri said that surface water quality has broader implications, and that area residents should value their local water by conserving and reducing pollution.

“The better the ecosystem, the better the human beings are,” Bieri said. “We really need to have some respect for what we have. We’re blessed.”

The next article in the series will cover past point source pollution to local underground and surface water.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.