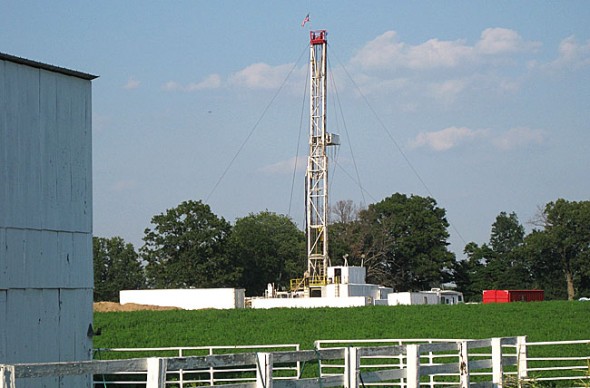

West Bay Exploration, a Michigan oil and gas company, had received a permit from the Ohio Department of Natural Resources to drill an exploratory oil well on a Miami Township property. Shown is a temporary drilling rig in southern Michigan, which is somewhat larger than what would be used in this area. (Submitted photo by West Bay Exploration)

Oil and water— Drilling stirs new concerns

- Published: April 19, 2012

LIQUID ASSETS

This is the sixth in a series of articles examining issues regarding local water.

• Click here to view all the articles the series

In the late 1800s northwestern Ohio was at the center of an oil boom. The Trenton-Black River limestone yielded so much fossil fuel that gas street lights in Findley burned 24 hours a day, oil baron John D. Rockefeller expanded his Cleveland-based corporate empire and Ohio became the world’s largest oil producer.

Most of those first Ohio wells were soon capped as oil production in the state peaked and declined and drilling moved to eastern and central Ohio, which is today at the center of another fossil fuel boom. There a new drilling method — hydraulic fracturing (fracking) combined with modern horizontal drilling — is releasing natural gas from deep underground shale, leading to a rush of new leases in such places as Carroll and Columbiana counties.

And in southwestern Ohio near Yellow Springs, the Trenton-Black River limestone will be drilled again as a Michigan oil drilling company hopes to find a pool of crude 1,400 feet below the surface. Although the local geology is poor for shale gas — and thus fracking — reservoirs here may someday be injected with fracking’s waste fluids, known as brine.

Some experts contend that toxic chemical fluids and hydrocarbons from production or injection wells near Yellow Springs threaten to contaminate local surface water, and that more should be done now to protect this natural resource. While local drinking water is sourced from groundwater rather than surface water, some are concerned that surface water infiltration could affect drinking water in the long run.

In contrast, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) Division of Mineral Resources Management argues that state regulations will protect water supplies and that such pollution is rare. Of the 60,000 oil and gas wells in Ohio, there are 144 documented cases of groundwater contamination, according to one state report.

But that prospect of contamination exists today in private water wells near the Acton property in Miami Township where a crew will soon drill an exploratory oil well. And one day the aquifer feeding Yellow Springs’ municipal water system may be similarly threatened, according to local soil scientist Julie Weatherington-Rice.

“This is a very real and very serious problem,” Weatherington-Rice said of the potential for contamination of municipal water supplies from oil and gas operations. Though accidents and spills are infrequent, the loss of a community’s source of drinking water would be catastrophic, she said.

“If public water supplies are not proactively prepared, then they’re going to be in a whole world of trouble,” Weatherington-Rice said.

Whether the Acton well is a gusher or a dry hole, the issues around oil and gas drilling in Ohio may be a factor as the Village of Yellow Springs explores its options for a safe and secure supply of water for decades to come.

A rig on the horizon

An oil derrick will soon rise 25 feet into the air two miles northwest of Yellow Springs, overshadowing sprawling farm fields and scattered residential enclaves. The temporary drilling rig will operate for 24 hours over several days to break through the ancient bedrock and reach a geologic layer which West Bay Exploration, of Traverse City, Mich., believes may contain significant amounts of petroleum.

After promising seismic tests in the area in early 2011, West Bay sought leases in the northwest section of Miami Township. Three contiguous property owners on West Yellow Springs-Fairfield Road signed lease agreements on 166 acres with West Bay last fall — the Acton and Delawder families and Fulton Brothers, Inc. In February West Bay obtained a state permit to drill on the Acton property. Drilling could be underway within the next month, according to West Bay Vice President Pat Gibson.

The field of water wells providing water for Yellow Springs is two miles from the planned oil drilling site and in a separate watershed, so it would likely be spared from surface contamination. Oil or other fluids spilled on the surface would seep down to the aquifer and flow by gravity in the direction of the nearest surface water, according to local geologist Peter Townsend, and pollution at the Acton site would head north toward Mud Run Creek, eventually draining into the Mad River near Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. Along the way, contaminants could pollute the private water wells of area landowners, endangering the health of those who use the water.

According to Ohio law, West Bay must replace a property owner’s water supply if the company contaminates it or reduces its supply. To get a baseline before drilling, Vickie Hennessy of Green Environmental Coalition organized well water tests for area landowners. West Bay offered to pay up to $5,000 for testing of private water wells for 13 neighboring properties along Yellow Springs-Fairfield Road as far east as East Enon Road and including several properties in the Lamont Road neighborhood. West Bay will also pay for the tests, which cost $425 per well, for its three lessors.

Some contaminants the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency recommends that landowners test for are known carcinogens. A natural constituent of crude oil, benzene can affect the bone marrow and cause anemia and leukemia in long-term exposure, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Together, Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons can affect the central nervous system, blood, immune system, lungs, skin, and eyes and have been shown to affect reproduction and the developing fetus in animals, according to the CDC. Barium, a compound used in drilling fluids, can cause gastrointestinal disturbances and muscular weakness in low levels and changes in heart rhythm, paralysis and death in high levels, according to the CDC.

Most contamination from oil and gas operations occurs when hydrocarbons, brine fluids or other chemicals used to bring a well to production are inadvertently spilled or leak from holding tanks, pits or distribution lines onto the surface, according to a 2011 report on Ohio incidents by the Groundwater Protection Council.

Contamination is exceedingly rare, according to the report. And the small scale of a conventional oil well, compared to hydraulically fractured, horizontal deep shale natural gas wells means less potential for serious pollution, according to Weatherington-Rice, a longtime soil scientist and geomorphologist. For example, 8,000 gallons of water are used in a conventional oil well, whereas it can take up to four million gallons of freshwater and a stew of sand and chemicals to hydraulically fracture a gas well, according to an ODNR fact sheet.

“It’s the scale of activity that determines the potential for threat,” Weatherington-Rice said. “We have accidents at all sizes and all kinds of drilling places. The question is how many contaminants you could potentially get.”

Of the 185 documented groundwater contamination incidents in Ohio since 1983, the single most common was the improper construction or maintenance of reserve pits that store drilling fluids on-site, according to Groundwater Protection Council report, “State Oil and Gas Agency Groundwater Investigations And Their Role in Advancing Regulatory Reforms,” by Steve Kell of ODNR. West Bay may use lined pits during some portions of drilling and will remove the drilling fluids once drilling is complete, Gibson said this week.

The largest number of contamination incidents, 74, took place during the initial drilling and well completion phase, representing 0.2 percent of all the wells drilled during the study. A further 39 incidents happened while the well was producing, 27 were from improper waste disposal, four occurred during plugging and reclamation and 41 at old orphaned wells, according to the report. None occurred during site preparation or when wells were hydraulically fractured.

“State oil and gas regulatory agencies place great emphasis on protecting groundwater resources,” Kell wrote in the forward, adding that the agencies have “broad authority” to regulate oil and gas exploration and production.

But Theresa Mills of the Center for Health, Environment and Justice, a national advocacy campaign started by environmental activist Lois Gibbs, said that regulatory oversight is lacking in Ohio and accidents are occurring.

“There’s a lot of times when they go and inspect the facilities and they find that the pits are overflowing and that so much has been spilled there’s oil on the ground,” Mills said. “I don’t think there’s much oversight in drilling at all, from start to end.”

Especially as the shale gas boom continues, inspectors may have a hard time monitoring well activity, some environmentalists have suggested. Though 192 shale gas wells have been permitted and 62 drilled in the last two years, ODNR officials estimate that 1,400 horizontal shale gas wells could be drilled in the coming years.

Ohio Attorney General Mike DeWine bolstered the concern of many citizens when he said earlier this year that Ohio’s drilling laws are inadequate. The state should have more stringent penalties for violations and require companies to disclose to the public, not just to ODNR, the chemicals it uses during drilling, DeWine said.

Gibson has argued that safety will be a priority for West Bay and that the company regularly takes more precautions than are mandated by the state. Since 2008 West Bay has drilled more than 50 oil wells in the Trenton Black-River formation in southern Michigan without incident, according to Joe Pettit, an enforcer with the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality.

“They are doing a lot of drilling in southern Michigan and have had absolutely no problem associated with the wells they are drilling,” Petit said. In the last 15 years, West Bay has received one notice of non-compliance when it was late to submit records in accordance with a new state law, Petit added. Earlier, in the 1980s, West Bay was ordered to clean up seven polluted well sites when groundwater was contaminated with benzene and other toxins. At fault was an improperly designed holding tank for natural gas, which Petit said was used by several different operators at 300 oil wells across Michigan and not the result of intentional contamination by West Bay.

From his experience, Petit said that most oil well contamination in Michigan has occurred during production, a phase many wells never see.

“Maybe 10 percent of drilled wells end up being economically producible,” Petit said.

The toilet of eastern Ohio?

If the Acton well fails to yield commercially viable quantities of petroleum and if the shale gas boom continues unabated in eastern Ohio and elsewhere in the Northeast, heightening the need for Class II injection wells for fracking fluid waste, might the Acton well be converted to waste injection? That possibility is worrying some environmentalists.

About half of 175 active injection wells in Ohio were converted from exploratory oil wells that never produced to injection wells, according to Bethany McCorckle, an ODNR spokesperson. To some that has implied that the Acton well might one day be a site for the disposal of brine.

“It makes perfect logical sense for someone to drill poor extractive wells in order to find space way down below,” said Jim O’Reilly, a Wyoming City Council member, lawyer and instructor at the University of Cincinnati College of Law. “The good news is you’ve found oil, or the good news is you haven’t found oil — you’ve found an empty space where you can put the toilet of Eastern Ohio.”

Gibson said that the West Bay has no intention of converting extraction wells to injection wells.

“I’m afraid I’m starting to sound like a broken record — we’re in the oil exploration business, we’re not in the [oil] services business,” Gibson said. “I’ve never even looked at it.”

West Bay does operate one injection well in Jackson County, Mich., which it uses to dispose waste from its numerous area wells. Gibson added that the leases signed in Miami Township don’t give West Bay the right to convert the use of the well. To do so would require another agreement with the landowner. And local geologist Townsend feels assured that the Trenton-Black River formation is not ideal for waste injection.

“The Trenton Black-River would not be suitable at all — period, exclamation,” Townsend said. But below the Trenton-Black River, around 3,000 feet, is the Mount Simon formation, which has been used for injection wells elsewhere in Ohio, he said.

O’Reilly said he believes the Mount Simon formation in southwestern Ohio, which is shallower and less porous than in other parts of the state, will be the likely reservoir used for the waste of the shale gas drilling frenzy. Further, the rail lines in southwestern Ohio would make transportation from the eastern area of the state easy, Weatherington-Rice said.

Since Ohio began requiring that brine be disposed of in Class II disposal wells rather than dumped in unlined earthen pits — the previous practice — there has not been a single incident of groundwater contamination from subsurface injection, according to the Groundwater Protection Council report. However, a Class II injection well outside of Youngstown caused nearly a dozen earthquakes there over the last year, including a 4.0 quake on New Year’s Eve, according to an ODNR investigation.

O’Reilly, who has published 45 textbooks and several environmental regulatory reports for government agencies, said he is concerned about what injection wells here would mean to the freshwater availability and the natural beauty of eastern Ohio. The millions of gallons of water used in each fracking well contain radioactive elements, keeping it from ever being returned to the water cycle, he said.

“I look at what’s happening here and I realize that the eastern part of Ohio, the bucolic hills, is going to look like western Oklahoma,” O’Reilly said. “It will look like a moonscape, with rusted wells and rusted tanks … I hope that people who are leasing their land realize that they are selling their legacy.”

Rights to oil and water

A more far-flung, but potentially more catastrophic threat is oil and gas extraction or injection in municipal water well fields. Last month Weatherington-Rice told a group of Ohio water and wastewater treatment operators that there was little they could do to keep oil and gas drilling from areas that are within one-year and five-year times of travel of municipal wellheads. In the audience was Joe Bates, the superintendent of Yellow Springs water and wastewater.

According to Weatherington-Rice, who worked on the Village of Yellow Springs’ Wellhead Protection Plan in the 1990s, oil and gas production in Ohio is covered by mineral extraction law, which doesn’t recognize community source water protection. Communities can be awarded damages after contamination occurs, but have a hard time preventing it, she said, especially after a 2004 Ohio law stripped away the rights of local communities to use zoning to control oil and gas development. Later, in 2010, ODNR was granted sole authority to regulate oil and gas production and removed the rights of communities to appeal, she added. O’Reilly also pointed to the recent legislative changes as worrisome.

“All the forces are coming together for the dramatic centralization of the decisions about what to extract, where to extract, what to dump and where to dump it and the safeguards that previously existed have been taken away,” O’Reilly said.

Currently there is nothing in Ohio law to protect public water supply well fields or recharge areas from oil and gas drilling, Weatherington-Rice said. Wells must be set back a minimum of 50 feet from streams and lakes and 300 feet from private or municipal water wells.

Concerned about the contamination of its sole-source aquifer from coal mining, Pleasant City, Ohio, petitioned ODNR in the late 1980s to designate their well field as unsuitable for coal extraction. ODNR granted the request, but was then sued and had to pay the company $5 million for the lost coal profit. When Barnesville, Ohio, asked ODNR to deem its greenbelt unsuitable for coal mining in 2001, ODNR denied the request.

While mineral rights are currently being protected above all else in Ohio, Weatherington-Rice said she hopes a 2010 constitutional amendment asserting a landowner’s rights in groundwater, lakes and other water courses may someday trump them.

There are proactive measures communities can take, Weatherington-Rice added. By setting a replacement value of a community’s water supply, oil and gas companies could be deterred from drilling in muncipal well fields. For example, the cities of Canton, North Canton and Massillon determined that if contamination spoiled their largest well field, it would cost them $139 million to replace the supply. The exorbitant cost of replacement may just be enough to “get companies to stop and think about it,” Weatherington-Rice said.

O’Reilly said that communities should also develop an emergency response plan if wells are contaminated by oil and gas operations or spills occur on roadways.

Whether Yellow Springs acts to protect itself from potential contamination, or to show solidarity with communities in eastern Ohio facing more imminent threats, there is much that can be done, Weatherington-Rice said.

“Yellow Springs has such a wonderful history of innovation and of being environmentally aware,” Weatherington-Rice said. “As a community you guys have always tried really hard to do things right and I’m looking for communities who want to be examples of that.”

One Response to “Oil and water— Drilling stirs new concerns”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

I think this is the best article that I have seen in the YS News on this subject so far. Now that the village now knows of the potential threat to their water supply (as I had previously stated many times), they can begin to petition the state legislature to amend the present law to change oversight of Oil and Gas Permitting in Ohio from the ODNR to the Ohio EPA.

West Bay Exploration intentionally contaminated an entire aquifer in Michigan over a period of seven years, including one and a half years after a “cease and Desist” order had been issued. Seven of their Oil Wells had serious violations. The YS News has copies of these orders and so does the Greene Environmental Coalition. The Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) had to seize the drilling equipment for the contamination to be brought to an end.

I do not trust this company. I do not believe for one minute that they would not attempt to convert a dry hole (well) to a Class II disposal well on any of their leases.

The citizens in Jackson, Michigan never thought their local well would be converted to a waste disposal well.

I recommend that the Village Council get involved in this today to protect their water supply.

Sincerely,

Mark Winkle

Environmental Consultant