BLOG – Kafka – evolving perceptions, and my personal history

- Published: December 10, 2015

Just in time for the cheerful holiday season, I’ll be posting a few articles exploring the life and work of Franz Kafka. But contrasting Kafka with cheerfulness is exactly what I want to explore – my personal relationship to him hasn’t been characterized by gloominess and scholarly perspectives on his life have been changing over the years in accordance with an evolving understanding of him as a person. As a Kafkaphile for over fifteen years, I feel it is my duty to talk a bit about everyone’s favorite Czech:

I was first introduced to Franz Kafka through the comic strip Calvin and Hobbes. In a Sunday strip published on November 8, 1987, Calvin asks his mom to give Hobbes a kiss goodnight. When Calvin asks why Hobbes was so insistent about getting a goodnight kiss, Hobbes says that if you don’t get one, you get “Kafka dreams.” Kafka dreams? I asked my parents what the weird word meant, and I was told it was the name of a person, a writer of odd short stories. It struck me as such a cool, strange name, like Xavier or another name that employs untraditional letter. And based on the fact that he wrote something that could give you weird dreams, I knew I wanted read whatever it was that he wrote when I grew up.

As soon as I could, I started reading Kafka, probably around ninth grade. I read everything of his I could find, adding biographies and criticism to his fiction as I got deeper. I had no conception of his renown or the reverence he was accorded – I simply found that his ideas and his utterly inimitable style of writing meshed well with whatever was echoing in my own imagination. I was taken by the fact that the majority of the characters in his stories and novels were known by only one strange name – Schmar, Harras, Wese, Klamm, Momus – something that again made perfect sense. There was something haunting, mysterious, and darkly playful in his writings, and I like that.

I didn’t ever really accord him the mystical powers some fans do, and I was never put a lot of stock in the idea that his oneiric bureaucracies were so frightening because they presaged the Nazis. My enjoyment was much more visceral. The immediacy of the reality he created spoke for itself. I liked that he wrote about the problems a small town faced after one of its citizens discovered a giant mole in “The Village Schoolmaster, or, the Giant Mole”; I immersed myself in his half-intentional/half-askew portrait of 1920s US in Amerika; I loved the send-up of officialese describing the missed connection of “A Common Confusion.” Kafka’s worlds weren’t ever impossible – they were grounded enough to be plausible, but they would seem like the weirdest day in your life, and I liked that he explored his singular ideas through this lens.

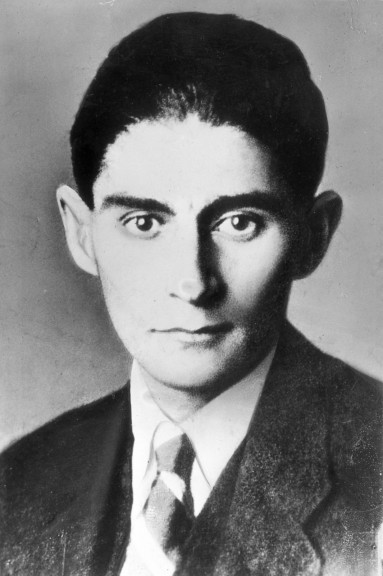

My fandom resulted in my second tattoo, a portrait of Kafka on my upper left arm. I got it before I left for college when I was still living with my parents, who had asked me not to get any more tattoos while I was still at home. Of course, as soon as they left for vacation – I had to stay behind to work – I hit up the guy who had done my first tattoo in his kitchen and asked him if he could do Kafka’s portrait. He said it would be $200, which, if the reader is knowledgeable about the cost-quality ratio of tattoos, meant that I was taking a big chance on recognizability for only $200. Indeed, the first iteration looked nothing like him, maybe a little if you squinted, but after some tinkering I was amazed (and relieved) to see how much a difference a little work on his lips could do. Soon I was satisfied. I had Kafka’s visage staring out at the world from my arm. It was a cool and odd feeling. My parents came home none the wiser. I knew they would be mad and I just wanted to get any confrontation over it, so I kept hoping they would see it peeking out from under my sleeve. Finally, when my mom was getting ready for bed after a long day driving home, she saw a kind of soap sitting on the counter that we never used. We only had it because it was the kind recommended tot take care of my first tattoo, and she immediately made this association. She sighed and asked where the new tattoo was. I showed her. I tried to reason that it kind of looked like my grandpa to no avail. She just shook her head, not wanting to get into an argument right before she was trying to go to sleep. She said she would wait to tell my dad until tomorrow for the same reason. I went downstairs and was in the bathroom when I heard my dad yell “He did what?!” Then he stomped down the steps and yanked open the door, demanding to see my arm.

My fandom resulted in my second tattoo, a portrait of Kafka on my upper left arm. I got it before I left for college when I was still living with my parents, who had asked me not to get any more tattoos while I was still at home. Of course, as soon as they left for vacation – I had to stay behind to work – I hit up the guy who had done my first tattoo in his kitchen and asked him if he could do Kafka’s portrait. He said it would be $200, which, if the reader is knowledgeable about the cost-quality ratio of tattoos, meant that I was taking a big chance on recognizability for only $200. Indeed, the first iteration looked nothing like him, maybe a little if you squinted, but after some tinkering I was amazed (and relieved) to see how much a difference a little work on his lips could do. Soon I was satisfied. I had Kafka’s visage staring out at the world from my arm. It was a cool and odd feeling. My parents came home none the wiser. I knew they would be mad and I just wanted to get any confrontation over it, so I kept hoping they would see it peeking out from under my sleeve. Finally, when my mom was getting ready for bed after a long day driving home, she saw a kind of soap sitting on the counter that we never used. We only had it because it was the kind recommended tot take care of my first tattoo, and she immediately made this association. She sighed and asked where the new tattoo was. I showed her. I tried to reason that it kind of looked like my grandpa to no avail. She just shook her head, not wanting to get into an argument right before she was trying to go to sleep. She said she would wait to tell my dad until tomorrow for the same reason. I went downstairs and was in the bathroom when I heard my dad yell “He did what?!” Then he stomped down the steps and yanked open the door, demanding to see my arm.

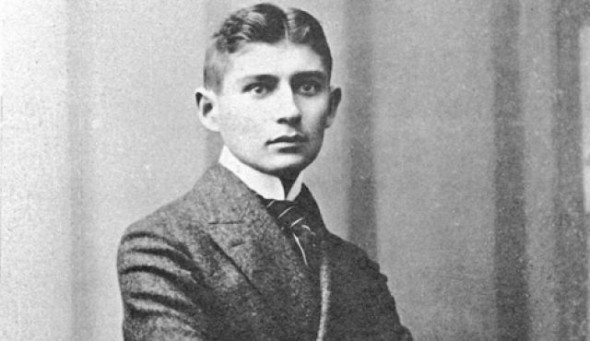

My parents gradually appreciated it and it only made my interest in Kafka deepen. The tattoo was stark and conveyed a lot precisely because the photo it’s based, a simple portrait of him when he was in his late 30s, says a lot. I was drawn to his Czech origins (a country I for some reason felt an immediate kinship with), his austere suits, and the fact that his name means ‘jackdaw’ or ‘crow’ in Czech for the same reason that I enjoyed exploring the worlds he had written about.

I don’t seem to be alone in drawing meaning from whatever it is that his appearance exudes. The first wave of Kafka scholars seemed to base all of their academic assumptions on their superficial reactions to his life and writing. This isn’t to say their readings aren’t valid, as of course their personal relationships to his writings are deeply felt, but a common mistake was conflating their perceptions with the reality of his life. Until fairly recently, Kafka was almost universally known as a sickly, paranoid, nebbish seer of a hellish future. Basically, there was no way the imagination behind his writings could belong to anyone but a man tortured by it. Kafka was read worldwide by the 1940s, and this was the perception that accompanied his growing fame.

But a new wave of scholars have reworked the understanding of Kafka into one that is more in line with the accounts of people that knew him, and not one dictated by the timbre of his writings or his piercing gaze. Anyone that knew Kafka remembered that he was immensely kind and charming, and that he spoke in a “mellifluous baritone” that colored whatever he was saying with sage-like gravity. He was athletic, funny, scrupulous about his appearance, and numerous diaries, letters, and books by his contemporaries attest to it. (One of my favorite stories is his reaction to a little girl he met in a park, who was crying because she lost her doll: he explained to her that the doll was not left but had left on a great adventure, and Kafka wrote the girl letters from the point of view of he r doll that updated the girl on her travels.)

r doll that updated the girl on her travels.)

And when something like a literary titan’s reputation gets overhauled, academic sparring will naturally follow. The debate between old guard Kafka scholars and newer, comparatively irreverent upstarts has been entertaining and intense, to say the least. One author, for example, really touched a lot of nerves when he claimed that Kafka had a deep interest in dirty magazines and that maybe the notorious “Letter to [his] Father” was just the whining of a spoiled middle-class kid. These revelations certainly have real implications for the study and interpretation of his work, and this debate is where this story will pick up next week.

Also to be discussed is a homegrown Kafka scholar’s contribution to Kafka scholarship. Kathi Diamant penned the first biography of Kafka’s last love Dora Diamant (no known relationship), his partner for the last year of his life and in whose arms Kafka died in 1924. For someone as widely studied as Kafka, there had never been a full investigation into Dora’s life, which was truly fascinating life in its own right. Without telling her story, Kafka’s would be incomplete. Her research for the book also kicked off a worldwide search for a lost cache of Kafka’s papers: approximately three dozen Kafka letters and twenty of his notebooks were confiscated by the Gestapo in 1933. There’s a chance this cache exists somewhere in an uncatalogued deposit of Nazi plunder, and Diamant is leading the treasure hunt to find it.

One Response to “BLOG – Kafka – evolving perceptions, and my personal history”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

Dylan, I love this! A beautiful weaving of the personal and factual. And some perfect phrases: “austere suits”; “nebbish seer of a hellish future”; stories that seem “like the weirdest day in your life.” Thanks for sharing this. I look forward to more.