Out of Something, Nothing: My Summer as a Professional Mover, part 5

- Published: March 5, 2016

Once in a while, a day was almost tolerable. Almost. People would be laughing and getting along well enough while working in the sun – it was almost like enlisting the help of a few friends of friends to install a cumbersome but ultimately awesome accessory to your house. The work was hard and annoying, but the payoff would definitely be worth the effort.

In fact, sometimes this exact scenario was a by-product of the job. It wasn’t uncommon for homeowners to give away stuff that didn’t have a place in the new house. There was always the chance that you’d score something outrageous on a job. One family gave away not one but two enormous old-school big-screen televisions. (“Big Boys,” in mover parlance.) Customers gave away gaming tables; others gave grills, chairs, desks; others gave away furniture whose sheer size cancelled out any question about its quality. As a result, a lot of the movers had become de facto experts on home furnishings. It was hilarious to hear curse-ridden debates about the merits of one brand of easy chair versus another. Tough dudes were constantly bragging that their houses were better furnished than yours.

It makes sense that the amount of time working around furniture is proportional to one’s knowledge of furniture. The same can be said of the irascibility of the average mover relative to time worked. Essentially, the longer someone has worked, the grumpier he’ll be.

As such, an extremely irksome character was the ultra-veteran. There were a handful of people that had been with the company for at least eight years and had earned the right to act like it. They weren’t totally unfriendly but approached everything you did with an extremely critical eye. They’d worked with every kind of employee, and they were justified in not wanting to work with people who aren’t going to pull their weight.

On my first day, I was shown that the proper way to work is to pick up something and move it as quickly as you can to the truck. Like, pick-it-up-and-run-with-it quickly. You’d then hand it to the guy packing the truck (if your crew was big enough to have a packer) or stash it yourself, and then run back into the house to grab more stuff to run right back out to the truck. This was the routine all day, every day.

I was able to practice this method my first day without too much difficulty, since I was primarily tasked with carrying a lot of boxes and stuff that you could one-man. But when I worked with a couple of vets for the first time, I learned that you move the largest, heaviest, most unwieldy pieces with the same speed. I was practically pushed backwards down the stairs carrying a bookshelf and I tripped over my feet as I was driven along by a washing machine shoved into my chest. That was just the way they worked, and if you didn’t want to get on their bad side, you had to learn to move as quickly and nimbly as they did.[1]

This approach served me well later when I moved myself or helped a friend. Picking up a box and running with it was reflexive. My brother’s roommate still talks appreciatively about how quickly her move went when I was there to help, though she also still laughs at the sight of a guy frantically running around the property with a large box.

One coworker was unphased by the work of a house/office mover because he had just transferred from an outfit that moved pianos exclusively. Only pianos, all day, every day. We were (un)lucky if we moved a piano once every couple of weeks but this guy dealt with music stores, piano tuners, instrument refurbishers, and schools on a daily basis. Working with pianos every day definitely didn’t make it easier, he explained, shuddering. Pianos were pianos. He was a nice guy by nature, but his good moods and enthusiasm were endearing because he seemed legitimately appreciative of his luck that he was now moving a variety of things.[2]

One guy I actually really liked was from Boston, and I had the good fortune of being assigned to work with him pretty frequently. I liked working with him because he didn’t care about what anybody thought, not in an overly tough kind of way but because he couldn’t be bothered to be bothered by anything he didn’t want to bother him. He was short and thick and had a crew cut. He boasted a few scars and his rough n’ tumble mug was made handsome by his bad boy charm. His speech was peppered with a bunch of New England slang and he said he’d been to prison, but he mentioned this in a way that was free of bluster or yearning for credibility. Being in prison was a life experience just like any other and it was matter-of-factly discussed as such. He was a pretty matter-of-fact guy.

Having someone open up to me about the fact that he was at one point in – gasp! – jail was flattering for its implied trust and because it also satisfied my voyeuristic interest in the prison experience. Feelings of my own toughness were made a little more tangible by the fact that we were driving around in a truck talking about it and smoking cigarettes. He noted that I smoked “rollies,” as I was rolling my own. I silently freaked out over the term, and I immediately began using the term among my friends, really casually like I’d always called them that. (I’m not a smoker, but in keeping with my obsession with being a real workin’ man, I smoked a few packs that summer.) He told me about prison smuggling operations, work-release programs, and inmate cliques. He told me that he had briefly taken up writing in prison. He wrote for a week straight and produced forty pages of a crime novel. He hadn’t picked it up after that and didn’t seem to have much interest in doing so, but he kept the manuscript and had it stashed somewhere in his house.

Did this really happen?

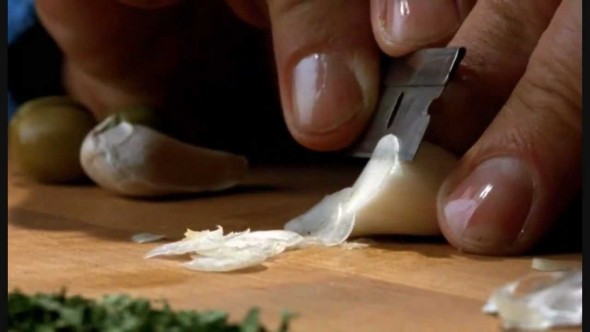

BUT there is the possibility that he wasn’t in jail at all. As odd as it sounds, some of the things he said were prison stereotypes of the kind that can be picked up from any TV show. For example: prison chess matches. He said he watched one person play against ten, the archetypical bookish prisoner who would inevitably win all the games. He also told me with a straight face about the dinners he and his fellow inmates cooked, which were apparently the stuff of legend. Everyone had a specific function – one guy took care of the pasta, one guy cooked the sausage, and the guy in charge of the sauce had this technique where he would shave the garlic into paper-thin slices with a razor blade so they would dissolve in oil. I was quite familiar with this scene as it appears exactly how he described in the movie Goodfellas, which was released in 1990 to widespread acclaim. I don’t know if he thought I hadn’t seen the movie or if he was somehow “testing” me to see if I would call his bluff, but I acted like it was true.

When a good conversation was underway, I could tell he knew it. The occasional look of appreciation would be exchanged, quickly followed by the sarcasm typical to male bonding. Sometimes it was hard to tell if his sarcasm was friendly or a way to tell me to shut up without actually doing so. I was always on guard that I was getting on his nerves. I had a good thing going with someone and I didn’t want to blow it. Sometimes we’d ride in silence for a while and I’d wonder if I’d been too eager to talk to him but then he’d bring up the aggravating traits of a coworker and we’d bond again over our mutual annoyance.

[1] New people were told that anything they broke came out of their paycheck. You were encouraged to be careful by the possibility that your entire week’s wages could vanish in a second if you accidently dropped a TV. In reality this wasn’t true. The company’s insurance paid for any damages. Good thing because at what we were paid, compensating someone for something expensive would have taken months. The only thing I ever broke was a huge mirror that I propped up poorly inside a truck. The client brushed it off as a no big deal but his mom made sure that it was replaced by the company, not that it was especially valuable but why wouldn’t you want to get a free replacement or a small check?)

[2] How moving a piano works: For small pianos, like the kind in your grandparents’ house, you bring in a four-wheeled piece of plastic or wood to sit the piano on. You have to pick up the piano to set it on the dolly, but you can at least wheel it once it is secured. Sometimes we’d make a ramp and wheel the piano on the board down the steps, but this was only if the steps weren’t steep. A lot of times people had pianos on their second floor, where the only way to move it was to pick it up and carry it down the steps. (You’d have to take care not to let the spindly legs sticking off of the keyboard get caught on anything.) For grand and baby grand pianos, you’d bring in a padded board that looks appropriately like the backboards used by ambulance crews. You unscrew the piano’s legs – one person unscrews while two tilt the piano – and then flip the piano ninety degrees onto the piano board. The piano is strapped down and then lifted onto a dolly or – surprise! – carried down the stairs.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.