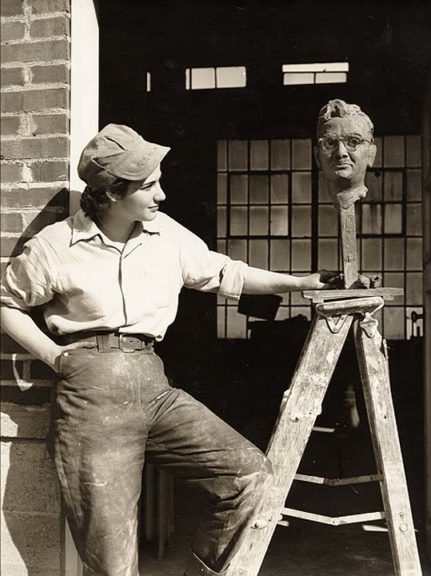

The Herndon Gallery will host a retrospective solo exhibition of works by sculptor Renata Manasse Schwebel, Antioch class of 1953, opening with a reception and a gallery talk by the artist on Thursday, July 13. The reception, from 4–6 p.m., will kick off events for Antioch College 2017 reunion this weekend. Shown here in her student days at the Antioch Foundry, Schwebel’s later work has focused on mid- to large-scale non-objective metal pieces. (Submitted photo)

A gutsy, pioneering sculptor

- Published: July 20, 2017

Thirty-three works by New York-based sculptor and Antioch alumna Renata Manasse Schwebel will go on display Thursday, July 13, in a new one-person exhibition at the Herndon Gallery on the Antioch College campus.

An opening reception from 4–6 p.m. and a gallery talk by the artist will kick off the college’s 2017 reunion activities this weekend.

Schwebel has dedicated the show, which will remain on view until Aug. 18, to her teacher and mentor, the late Amos Mazzolini, who was brought to the college in the 1930s by Arthur Morgan to oversee the Antioch Foundry.

In a recent phone interview from her home, the now 88-year-old artist talked about her college years, becoming a sculptor and pursuing her passion in a field dominated by men.

“When I entered Antioch, that was back in 1948, I had only applied to Cornell and Antioch,” she said. A family friend in academia told her that if she had enjoyed high school and wanted to continue that experience, she should choose Cornell. But if she “was ready to be a grown up,” she should go to Antioch.

“He convinced me,” she said.

PUBLIC REUNION EVENTS

Antioch College reunion 2017 officially runs Friday through Sunday, July 14–16. Several events, in addition to the Herndon Gallery exhibition, will be open to the public. They include:

• A keynote address, “Speaking Truth to Power,” by Derrick Johnson, vice chairman of the NAACP National Board of Directors, 3 p.m. Friday, July 14, in the South Gym.

• A concert by student act Matthew Human, 4:30–6 p.m. Saturday, July 15, in the front room of Weston Hall. Admission is free with donations welcome.

• A plaque dedication in honor of the late David Case, ‘43, and Hardy Trolander, ‘47, who got YSI off the ground in 1948 and ‘49, 11 a.m. Sunday, July 16, in the lobby of the Arts and Science Building.

She started the then five-year program interested in painting, economics and political science. But a class with Mazzolini that first fall on campus changed everything.

“I fell in love with sculpture,” she said.

And she was beguiled by the foundry. “He (Mazzolini) had a most wonderful foundry, perhaps the finest foundry in the world at the time for art casting. The craftsmanship was unbelievable.”

She said Mazzolini, who “taught by example more than words,” was also “a first-rate sculptor in the traditional vein.”

She started spending a lot of time at the foundry — “I loved the pouring of the bronze,” she recalled — and she asked about working there.

“He wasn’t exactly planning on having a woman around,” she said, adding that he initially told her that “women don’t work in the foundry.” But she persisted, and Mazzolini relented. And once that hurdle was jumped, he couldn’t have been more generous with his time and expertise, she said.

In addition to classes and working in the foundry, Schwebel participated in student trips led by Mazzolini. And by the time she graduated in 1953 she called him a friend. She visited with him a last time when he was dying in 1957, and he gave her his modeling tools, which she still treasures.

Her first commission as a working artist came in 1953 with Antioch’s 100th anniversary celebration. She said a giant cardboard cake was created to honor the milestone, and she was asked to make a statue of Horace Mann to sit on top of the cake.

As a new graduate, she stayed in Yellow Springs for a year working at the college, and then entered graduate school at Columbia University.

Marriage and the start of a family slowed her graduate work, but she earned her master of fine arts degree in sculpture in 1961.

Living in New Rochelle and Westchester County, New York, she and her husband, Jack, raised three daughters and she became involved in progressive political causes. She also continued making art, taking classes with the sculptor Helen Beling, who became a close friend.

For a time her work focused on portrait and figurative sculpture, she said. But she became dissatisfied with her artistic process. “I realized I was concentrating so much on details, I was missing the totality.”

She decided to go in a more abstract direction and begin working with such metals as aluminum and stainless steel. She took courses at New York’s Art Students League from 1967–69, and then participated in the summer welding workshop at the Hobart Institute in Troy, Ohio, in 1972.

She said she started “working with hard-edge non-objective forms,” and she loved it.

An irony for her is that in wanting to focus less on details, she moved into a process where “if you’re off by a 36th of an inch, the piece was ruined.”

She rented an abandoned laundromat as a studio for her metal work. It had an abundance of electrical outlets and was spacious enough for her large-scale work.

In equipping it with the machinery she needed — including a drill press, band saw and welding tools — she ran into some difficulty being taken seriously as a woman. But she was quick to ask condescending suppliers if they talked to men the same way.

She personally needed the equipment because unlike many sculptors, Schwebel did her own construction. It’s common for artists, especially as their profiles rise, to create the designs and leave the manual work to assistants. Not Schwebel. “I love to do my own work,” she said.

“I find that the feel of the material and the handling of tools is as much a part of the joy of sculpture as the originating of ideas,” she writes in her artist biography.

And while she continues doing as much of her own work as possible, getting a pace-maker in her late 70s ended her days with a welding torch. Nevertheless, she and one of her daughters will be driving to Antioch with a load of her work in tow.

Jennifer Wenker, creative director at Herndon Gallery, said she is impressed by Schwebel’s work and life, which she described as “gutsy.” She said the solo restrospective will include a variety of small and mid-sized abstract works and maquettes.

Over the years, Schwebel has participated in a variety of group shows and had a number of solo exhibitions. Her work is in the permanent collections of such places as Columbia University; Heinrich Gruber Haus, in Berlin, Germany; the Housatonic Museum, in Bridgeport, Conn.; the Jule Collins Smith Museum, in Auburn, Ala.; and the Museum of Foreign Art, in Sofia, Bulgaria.

Schwebel traces her love for “the direct handling of metal” back to her time at Antioch. It set the course of her life, she said.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.