On the job for almost a year, Yellow Springs native Rose Pelzl is one of two Village employees who read water meters by hand, about 2,200 meters a month. About half are located outdoors, half indoors. Here she’s pictured closing a gate at a home on Elm Street, part of “route 1,” the first of 17 defined routes around the village. (Photo by Audrey Hackett)

‘I’m your meter reader’

- Published: October 10, 2019

Rose Pelzl reads meters.

In the year since she was hired by the Village of Yellow Springs, Pelzl has become a friendly, knowledgeable force for accurate and timely readings of villagers’ water meters — some 2,200 in all. She’s become passionate about helping local utility customers detect leaks that can add needless charges to their monthly bills. And Pelzl, a sixth-generation Yellow Springer, has found a sense of calling in a job that serves residents and businesses in her hometown.

“It’s sort of a dream job,” she said in a recent interview with the News.

A self-described “local government nerd,” Pelzl previously served for three years on the Village Planning Commission, including one as chair. She explained that her new job feeds her curiosity to understand “the backsides of things” — whether planning decisions or physical infrastructure.

“I learn something new, literally every day,” she said.

Pelzl, 29, is one of two meter readers currently employed by the Village. The other is Travis Tarbox Hotaling, who also grew up here. Pelzl is full time, Hotaling part time. Between them, they endeavor to read all of the village’s water meters every month.

It’s a job they accomplish door-to-door, on foot.

The village is divided into 17 routes, with anywhere from 80 to 150 residential and/or business meters on each. About half of local water meters are located inside homes or businesses, half on remote devices or in meter pits outside buildings.

“Some people weren’t sure it could be done,” Village Public Works Director Johnnie Burns said of the monthly reads.

Until 2016, electric and water meters in the village were read every three months. But then the Village changed over to remote-read electric meters, which allow for drive-by reads one day a month. With the time savings, Village meter readers were challenged to read water meters every month — a frequency that yields better accuracy and more timely detection of leaks, according to Burns.

The monthly readings take up to three weeks of Pelzl’s time each month, with the balance used for meter change-outs and repairs, work orders for final reads and shut-offs and other projects. For example, Pelzl is geo-locating hydrants, meter pits and other elements of Village infrastructure as part of a new initiative to create comprehensive, multi-layered GIS maps of Village assets.

Burns has been impressed by Pelzl’s drive, accuracy and enthusiasm for all aspects of her job.

“Rose has an attention to detail that’s remarkable,” he said. “And she has a passion for her job that anyone who comes in contact with her can feel.”

‘I’m your meter reader.’

On a recent hot Friday morning, this News reporter took a walk with Pelzl as she read meters on Elm and Phillips streets, and one residence on Dayton Street.

Around her neck was a laminated, color-coded map for “route 1,” one of 17 such maps Pelzl made soon after she took the position last October. The maps supplement the information in her handheld device, offering a more visual orientation to the routes.

Our first stop, just before 9 a.m., was a home whose meter was in the basement, accessible by a bulkhead out back. Pelzl knocked on the door first, got permission to enter the basement from the outside, and disappeared down concrete steps. Less than a minute later, she was back, and we continued on to the next house, and the next.

“I’m your meter reader. Can I come in and read your meter?”

The residents at the home were new to town, and Pelzl was meeting them — and their bulldog, Elvis — for the first time.

Pelzl came prepared.

“Can I give Elvis a treat?”

The dog, and his owners, concurred, and Pelzl dispensed one of the gluten-free dog treats she carries as an essential part of her meter-reading “gear.”

Next, we crossed over to St. Paul Catholic Church and entered by a side door. Pelzl inspected the meter.

“It’s a little high,” she said, checking the current read against last month’s, accessed from her handheld device. All meter readings get entered into the device.

But the red triangle-shaped indicator on the church’s meter wasn’t spinning — the sign of active water usage, or a leak — and she decided to check the meter again in a week.

Pelzl is always on the lookout for leaks.

Outside spigots, toilets and water softeners are the usual suspects.

“But it’s mostly the toilet — and you don’t always hear it,” she cautioned.

Sometimes she detects a leak through the slow spinning of the meter. Other times the leak is too slow to be detected. That’s when she recommends people do a “dye test.” Dye tablets are available at the Village offices. If you put the tablet in the back of your toilet and dye shows up in the bowl — you have a leak.

“It’s really important for people to know this stuff,” she said.

A leak, even a slow one, can lead to bafflingly high water bills. She’s experienced that herself: the year before she was hired as the Village meter reader, she spent a whole year paying off in installments a whopping water bill traceable to an undetected toilet leak.

Sometimes spotting water waste is as simple as noticing that a spigot attached to a garden hose has been left on in a resident’s absence. In that case, Pelzl turns off the spigot, and leaves a note for the resident.

During our route, one resident left a note for us.

Pelzl had contacted several customers ahead of time to ask permission for this reporter to accompany her into their basements to see, first hand, how she stoops, kneels, reaches and crawls to locate and read the meter.

In this particular instance, the homeowners, Parker Buckley and Carol Young, had left their key under the mat, and taped a friendly note to their basement door.

“Welcome to our basement,” it read in part.

“I love Yellow Springs so much,” Pelzl observed, adding that customers are usually “so nice” and rarely rude.

But that doesn’t mean confusion over water usage and billing doesn’t arise, sometimes leading to tensions between customers and Village staff. And three years ago, as the Village was simultaneously changing its systems and billing cycle, Village billing errors and customer confusion coincided to intensify tensions.

Pelzl sought to clear up for this reporter, and for Yellow Springers, a few common misconceptions.

Understanding usage

The first has to do with water usage. The average adult uses between 2,000 and 4,000 gallons of water a month, according to the EPA. Even people who think they “don’t use any water” probably use more than they think, Pelzl said.

“Rarely does a person living alone use less than 1,000 gallons,” she noted.

A single toilet flush from an older toilet can use up to six gallons, though newer models use between one and two gallons, according to the EPA.

Usage within a household can fluctuate significantly based on factors such as having house guests or watering the yard during a dry summer.

Billing adds another layer of complexity. The Village reads and bills water usage monthly in 1,000-gallon increments, and rounds down to the nearest 1,000 gallons. Month to month, that means billing amounts might fluctuate even when usage remains relatively consistent, and vice versa, that billing might stay stable despite a variance of underlying usage.

Pelzl provided examples of both scenarios.

In scenario one, if the starting read is 300,000 (Village water meters show cumulative use), and the next read is 303,900, the customer has used 3,900 gallons that month. But because the Village rounds down, the customer will be billed for 3,000 gallons of usage.

If the read the next month is 308,100, the customer has used 4,200 gallons, but will be billed for 5,000, including the 900 gallons unbilled from the previous month.

Similar usage levels, but a swing in billing.

In the second scenario, if the starting read is 114,000, and the next read is 117,980, the customer has used 3,980 gallons, but will be billed for 3,000 gallons.

If the next read is 120,100, the customer has used just 2,100 gallons that month, but will again be billed for 3,000, including the 980 gallons previously unbilled.

Disparate usage levels, but the same amount billed.

Pelzl encourages those with water meters in their home to track usage themselves.

“You’re lucky if your meter is inside. You can read it for yourself and see your usage,” she said.

Of course, sometimes people can’t afford to pay their bills. Pelzl encourages villagers to reach out to the utility department to work out a payment plan or access other help. The new “Round Up” program, which encourages villagers who can to round up their monthly payment amount to help those in need, has begun to create a fund for those having trouble paying their bills.

It’s part of Pelzl’s job — the most difficult part — to turn off utilities for non-payment.

“I love my job so much, and I hate that part of my job so much,” she said.

She herself has been shut off in the past, and she keeps that experience in mind when she has to shut off fellow villagers.

“The best thing we can do is to be fair and clear about policies. And be kind,” she said.

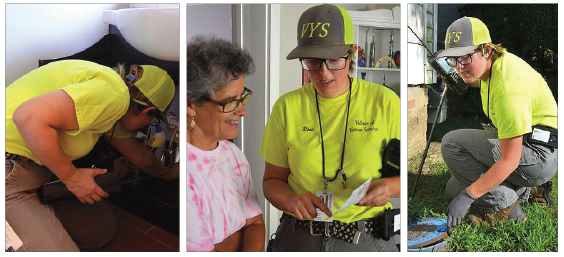

LEFT: Pelzl read Yellow Springs resident Susan Harrison’s water meter on Dayton Street, awkwardly located under a sink. The Village plans to eventually shift to automated reading, but that change is likely years away. | Center: Pelzl chatted with Harrison after reading her meter. Talking with customers, who are also neighbors and friends, is part of the pleasure of the job, as well as giving Pelzl an opportunity to explain Village billing, troubleshoot potential leaks and share information about water usage. | right: Using a “pit tool,” Pelzl loosened a pit cover to access a water meter on Phillips Street. Water meter pits are cozy places for snakes, salamanders and other critters; Pelzl encountered four snakes in a pit on her first time out on the job. (Photos by Audrey Hackett)

Change is coming

The last stop on our route that morning was a home on Dayton Street. The resident, Susan Harrison, greeted us warmly.

“I’m so happy you’re here to read my meter,” she said.

Her water meter was located awkwardly under a sink in the bathroom, requiring a flashlight and a champion reach. Fortunately, Pelzl had both.

“Why can’t the Village remotely read that one?” Harrison asked.

Pelzl explained that the Village wasn’t changing over even relatively hard-to-access inside meters because it intends to make a more wholesale change: a shift to automated meter reading.

“Won’t you lose your job?” Harrison asked.

Pelzl reassured her that the planned change, likely several years down the road in implementation, wouldn’t threaten her employment.

According to Public Works Director Burns in a recent interview, the Village is exploring options to convert its water meters to a fully automated system. Such a system would eliminate hand reading, replacing it with digital meters that transmit data wirelessly to the utility office. The process could take as little as 45 minutes each month. This method is distinct from the drive-by system the Village uses for electric readings.

One advantage of the fully automated system would be early leak detection, in the form of automated alerts direct to customers for high water usage, according to Burns.

“I’m looking forward to the days we won’t have to read meters,” he said, citing the time-intensive nature of the job, as well as safety and liability issues.

The Village last summer applied for, but didn’t receive, a grant to offset the cost of the change-over, which at the time was estimated at nearly $1 million.

“We’re still trying to figure things out,” Burns said.

Converting a few routes at a time over several years is the likeliest scenario, he added.

Pelzl said she would miss aspects of the job, but would be glad to avoid some of Yellow Springs’ spookier basements — and to branch out into other aspects of Village infrastructure.

“I’m just happy to learn new things,” she said.

Burns emphasized that Village meter readers would not lose their jobs because of the change. And he stressed how much work remained to be done on the GIS mapping initiative and other projects.

“Even if we didn’t have to read meters beginning tomorrow, we’re booked up months on end with maintenance issues,” he said. And GIS mapping alone will likely take three to four years, Burns added.

‘100% accepted’

Pelzl is currently one of only two women on the Village public works department, and she’s also one of the youngest.

She has felt “100% accepted” as a member of the crew, she said.

“I feel respected, my input is listened to. No one treats me any differently,” she explained.

A 2008 GED graduate, Pelzl previously worked in construction, and was employed for two years at Morris Bean as a finisher. The company paid for her to attend welding school, and she was subsequently employed as a welder on third shift, a schedule she found hard to keep. When the opportunity to work for the Village came up last fall, she jumped at the chance.

She has nothing but praise for her new colleagues and working environment.

“I’m extremely impressed with my co-workers,” she said.

While Yellow Springs residents tend to emphasize the importance of Village workers living where they work, her experience on the public works crew has shifted her perception.

“I don’t see any difference in the level of care between Village employees who live here and those who don’t,” she said.

“I’m proud of how responsive they are, and how passionate they are about their work,” she added.

Referring back to her “local government nerd” leanings, Pelzl said serving on the Village crew is easily the most fulfilling work she’s done.

Her experience with Nonstop Antioch during the college’s closure — she’s a fifth-generation Antiochian — created a “participatory government hole in her heart” that she’s always looking to fill.

Working for the public works department has gone a long way to filling it.

For Yellow Springs flora and fauna from a meter reader’s perspective, check out http://www.instagram.com/meter.reader, where Pelzl and Hotaling post photos from their routes.

Contact: ahackett@ysnews.com

Comments are closed for this article.