A closer look at COVID’s first wave

- Published: June 18, 2020

Editor’s Note: This this article was first published in the print edition of the Yellow Springs News, on Thursday, June 11, several new trends have developed, including an uptick of cases in Southwest Ohio, including Greene County. In addition, COVID-19 testing is now available to all Ohioans, even those without symptoms. Read the latest update in the June 25 print edition of the News.

Last Friday, 78 villagers swam at the Gaunt Park pool on its first day since reopening for the season with new, state-mandated social distancing and sanitation measures.

On the same day, the restrooms at the YS Train Station were opened to the public for the first time in months. This week, the Village’s outdoor playgrounds and basketball courts are reopening, and the John Bryan Center gym is slated to reopen its doors on June 15. And after state restrictions were lifted over the last month, most local retail shops and restaurants are back in business.

Yellow Springs is slowly opening back up with the rest of the state.

Since the beginning of May, Ohio has opened its economy apace after swift business and school closures and stay-at-home orders were enacted in mid-March to slow the spread of COVID-19. State leaders have pointed to those actions as having “flattened the curve” of infections and avoided overwhelming hospitals and ICU capacity.

In fact, the disease has been relatively mild in Ohio, which as the seventh most populous state ranks 19th in cases. Greene County has fared even better; as the 18th most populous county in Ohio, it is 39th in cases.

Most critically for state leaders, Ohio’s coronavirus reproduction number, which indicates how many other people one sick person infects, has fallen from 2.8 people infected for every known case in late February to just 0.8 people by the end of May. Instead of growing exponentially, the number of new infections is falling. Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine addressed the statistic at his press briefing last Friday.

“Because of that, we are able to move forward, cautiously, carefully,” DeWine said of the reproduction number, adding, “The virus is still there, just as lethal.”

Only a few activities have yet to be allowed in the state, after amusement parks, water parks and casinos were given the green light last week to open on June 19. Also last week, a variety of recreational facilities, from movie theaters and playgrounds to aquariums and zoos, were approved to open on June 10. Although professional sports and high-contact youth sports remain prohibited and large venues like auditoriums and stadiums remain closed, state leaders have vowed to allow them to open soon.

In light of reopening, the News reviews how the pandemic has played out so far in the village and county, and looks at plans to reduce the spread of the virus as the shutdown comes to an end.

And while perspectives on reopening vary, the messages from local and state officials about the importance of caution in moving ahead are consistent.

“The problem [with reopening] is that suddenly people think the risk is gone,” Miami Township Fire Chief Colin Altman said on a call with business leaders last week. “It’s important … to not get too complacent,” he added. “Social distancing is the single most important thing we can do to prevent a large-scale return of the virus.”

At last week’s briefing, DeWine implored Ohioans to continue to be vigilant in the face of the novel coronavirus, which he said is “still very much out there” despite a downward trajectory statewide in confirmed cases and deaths from COVID-19 in recent weeks.

“These are times when caution and good judgement are required of all Ohioans,” he added.

COVID in YS, county

Yellow Springs emerged from the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic with few confirmed cases.

Tragically, one villager died on April 18 after being hospitalized with COVID-19 more than two weeks earlier and placed on a ventilator to assist his breathing. The 50-year-old believed he contracted the illness at the Columbus call center where he worked, and experienced an onset of symptoms on March 22.

A second local case of COVID-19 was confirmed in May, according to Yellow Springs Police Chief Brian Carlson, who monitors daily updates on a shared countywide spreadsheet for first responders. That resident was also believed to have been exposed at his or her workplace, which in this case was in a neighboring county. By the end of the month, the person recovered, and was no longer on the county’s list of individuals self-isolating. (Patient privacy laws protect the identities of confirmed or potential cases.)

In addition, at least three other Yellow Springs residents were monitored by Greene County Public Health for a two-week period of self-quarantine after potential exposure to someone who was confirmed to have the disease, according to Carlson.

But as of Monday, June 8, there were no confirmed cases in the village or any individuals who were self-quarantining under county orders. At the time there were 12 people across the county actively recovering from the illness, down from 19 active cases two weeks prior, according to figures shared by Carlson.

In fact, data from the Ohio Department of Health has shown a decline in cases in Greene County over the last few months. The county experienced its first peak on March 24, followed by another peak on April 4, according to county epidemiologist Dr. Don Brannen in late April.

The first person in the county to come down with the disease had symptoms beginning on Jan. 23, but the month with the most number of people seeing an onset of symptoms here was in March, with 43 people getting sick. In April, 28 came down with symptoms, mostly in the early part of the month, 29 got sick in May and in the first week of June six people developed symptoms.

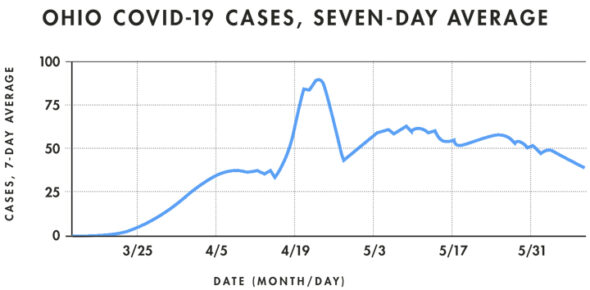

Greene County appears to have peaked slightly earlier than the rest of the state, which reached its highest number of new daily cases on April 19. Asked about the difference, Brannen said that the county’s contact-tracing efforts and isolation of known cases had an impact, along with other factors such as geography.

“Our county is set up so people drive everywhere instead of everyone walking, which is typically not a good thing,” Brannen said. “But in this case it seemed to work to our advantage to not have that congregation.”

According to Ohio Department of Health figures, which now include probable cases tied to positive antibody tests, on Tuesday, June 9, there were, cumulatively, 114 total cases of COVID-19 in Greene County (78 confirmed, 36 probable). Of those, 17 people had been hospitalized and five people had died.

Greene County’s measures are comparatively low. With a countywide population of around 169,000, Greene County’s rate of infection is 67 people per 100,000 and death rate is 3 people per 100,000. That’s lower than the state’s case rate of 335 per 100,000 and death rate of 21 per 100,000. And both are below the U.S. case rate of 614 per 100,000 and death rate of 34 per 100,000, according to figures from the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.

“Overall, Greene County has been doing very very well,” Carlson observed.

Last week, Greene County lifted its state of emergency, which went into effect on March 17. That action, and the recent data, are good news, according to Salmerón this week.

“Yellow Springs does not currently have an active threat,” he said. “As for Greene County, I feel confident in what we’ve done to flatten the curve.”

Salmerón said, however, that he continues to monitor the situation in nearby counties, since “we don’t live in a bubble,” and Yellow Springs, through employment and tourism, is connected to nearby counties, such as Clark and Montgomery.

“We can assume we have significant exposure to people in those counties,” he said.

But cases in those counties are also leveling off, Salmerón observed. In addition they were never as high as figures in major metropolitan counties such as Franklin or Hamilton.

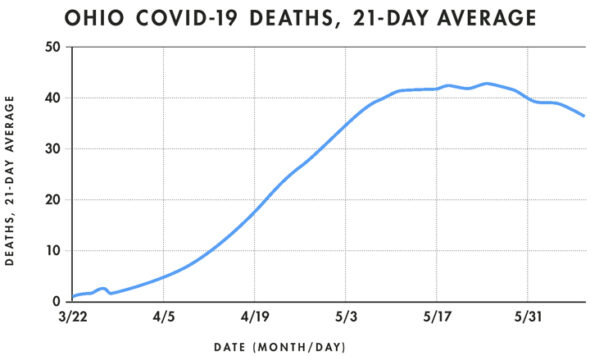

In Ohio, and the U.S., indicators of the disease have also trended downward in recent weeks. In Ohio, deaths reached a seven-day average peak of 49 per day on May 23–24 and had fallen to 28 per day earlier this week, which is on par with deaths on April 17.

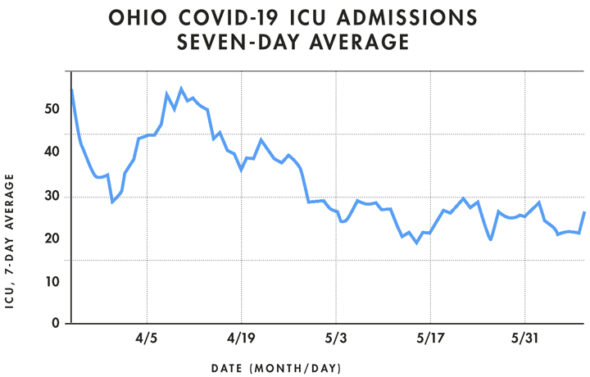

Statewide cases, too, are down from their seven-day average peak of 897 new cases on April 23, reached in part due to an increase in testing in prisons, to 408 new cases this week. While the seven-day average for new daily hospitalizations has hovered in the 80s since mid-April, it has finally dropped in the last two weeks into the 60s. Daily ICU admissions, meanwhile, are on a downward trajectory, yet have remained consistent through May at around 15 people per day.

Cumulatively, Ohio recorded 39,162 cases and 2,421 deaths as of June 9.

In the U.S., the seven-day average of deaths per day peaked at 2,082 daily deaths on April 20, falling to 851 on June 7, according to data compiled by Financial Times. In total, the country has had nearly 2 million cases and more than 111,000 confirmed deaths, the most deaths of any nation in the world.

Who’s getting sick?

A closer look at the state data shows that the risk of contracting, and dying from COVID-19, is not the same for all people. One’s age and race, place of employment, current health conditions and whether or not one lives in a congregate facility appear to be the most significant factors.

The vast majority of COVID-19 cases, about 80%, are either mild or asymptomatic, meaning the person doesn’t show symptoms, the World Health Organization has observed. Most people will recover from COVID-19 in about two weeks.

The fatality rate is currently hard to measure as the true incidence of the disease is unknown, but an estimated 1.3% of those who show symptoms die, according to a University of Washington study published last month. That’s higher than the comparable rate of death for the seasonal flu of 0.1%, researchers noted.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, the biggest risk factors for developing a severe COVID-19 illness are being 65 years of age or older, living in a nursing home or long-term care facility, or having an underlying medical condition such as asthma, chronic kidney or lung disease, diabetes, hemoglobin disorders, liver disease, serious heart conditions or severe obesity, or being immunocompromised.

It’s unclear how the relative risks affect villagers. However, some 45% percent of Yellow Springs’ population is 65 or older, according to the latest Census figures.

Currently, 70% of all deaths from COVID-19 in the state have been in nursing homes. The combination of close living quarters and an older population increase the vulnerability of nursing home residents to the disease. Of the 2,404 people who have died in the state, more than half (53%) were over age 80, while 3% of fatalities were among those under 50. No one under 20 has died from the disease in Ohio.

Friends Care Community has so far not had a confirmed case. But that doesn’t mean Friends Care is loosening any restrictions yet, according to Friends Care Director Mike Montgomery in a call with business leaders last week. Although the state has allowed outside visitation for members of assisted living communities, Friends Care has decided not to allow it in order to protect the residents of its adjacent nursing home, he said.

“Window and virtual visitations are still encouraged and welcomed,” Montgomery noted.

Of the 21 nursing homes in the county, five have had cases, with four staff members and two residents infected. There have been no deaths.

An additional 3.5% of the state’s cases can be traced to prisons. Two prisons, Marion Correctional and Pickaway Correctional, have seen the largest clusters of cases, pushing their countywide per capita infection rates to the state’s highest, at 4,118 per 100,000 in Marion County and 3,668 per 100,000 in Pickaway County, compared to 67 in Greene County.

There is a racial factor, as well. Although 78% of all deaths have been among whites, Black people accounted for 18% of deaths, despite making up only 14% of the population. Hospitalization rates show an even more dramatic racial gap, as 31% of the 6,550 people hospitalized for COVID-19 were Black. State leaders have cited unequal access to healthcare and paid sick leave and socioeconomic factors as reasons cited for the disparity.

Workplace exposures are yet another area of concern. The most significant risks are borne by healthcare workers, who make up 15% of the state’s cases. (Healthcare workers also have been among the groups in the state prioritized for testing.) Facilities in which social distancing is difficult, such as call centers and meatpacking plants, have also been disproportionately impacted throughout the country.

Through contact tracing, Greene County Public Health found that county cases were associated with travel, the airport, the Dole processing plant in Springfield, Wright-Patterson Air Force base, healthcare facilities, and a funeral, among other sources.

What’s ahead: Contact tracing, testing

Earlier this week, World Health Organization officials said they found it was “very rare” for people who are not showing symptoms, and never go on to develop symptoms, to spread the virus to others. Previously, so-called “asymptomatic carriers” were thought to play a major role in spreading the virus when they didn’t know they were sick.

That new information prompted Gov. DeWine to invite an Ohio State University doctor to discuss the issue at his press briefing on Tuesday.

“We continue to learn something new every day about this disease,” Dr. Susan Kolertar said in response to the WHO release.

But the WHO statement only applies to people who never go on to develop symptoms, not people who are pre-symptomatic, Koletar emphasized. Individuals could still spread the disease after they contract the virus but before they develop clear systems.

Kolertar said that the new information doesn’t change the state’s approach, and reiterated the importance of social distancing, wearing masks and staying home when sick.

“We have to be very cautious in terms of how we feel,” Kolertar said.

The latest update from the WHO, however, may be good news when it comes to the county’s approach to contract tracing, in which those who are ill, or who may have been exposed, are isolated so that they will not infect others.

During contact tracing, the county tracks down those who had close contact with someone who later was confirmed to have COVID-19 and asks them to “self-quarantine” for two weeks by staying at home. Since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, Greene County has followed up with “well over 200 people and their contacts,” according to Brannen, the county epidemiologist, who runs the contact tracing team.

“It’s part of a process that public health does all the time,” Brannen said, noting previous cases of norovirus and salmonella that the county has traced to individuals or facilities.

According to Brannen, Greene County Public Health is informed of a confirmed case of COVID-19 by the state (they do not receive negative test results). Public health officials interview the person and trace their movements for the previous 14 days and then check with those they have come into contact with. Specifically, the county is looking at places where “close contact” occurs, such as at work or within someone’s home.

Although in some cases it’s unclear where an individual contracted the virus, which is then categorized as “community spread,” the source of most can be determined, according to Brannen.

“Most cases can be traced to a particular subject,” he said.

Once a person has been asked to self-quarantine, they are required to text their temperature to the county twice per day. Typically, those individuals have not been tested unless they are a healthcare worker, an employee at a long-term care facility or a first responder, Brannen explained.

But testing is not as limited as it once was in Ohio. Last week, DeWine said while the state had previously focused on those high-risk groups, as well as those hospitalized with symptoms, testing is now being made more readily available.

“With expanded testing, healthcare providers are able to test anyone with symptoms,” DeWine said.

Ohio has moved more slowly to expand testing here after the CDC shifted its testing recommendations on May 3 to include as a “priority” people with symptoms of a potential COVID-19 infection, including fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, muscle pain, new loss of taste or smell, vomiting or diarrhea and/or sore throat.

Currently, the state is testing around 8,000 to 9,000 people per day for COVID-19. That is up from 2,000 to 4,000 per day at the end of April, but far below the 22,000 per day by May 15 that a Harvard Global Health Institute study found would be necessary for the state to reopen safely.

Addressing that gap in testing at a press briefing last month, DeWine said, “We’re not satisfied with where we are,” adding, “We have the confidence that we will continue to move that up.”

DeWine said late last month that the state had contracted with a new company to secure the reagents used in tests, which were in limited supply. And last week he said that soon some private pharmacies such as Kroger and Walgreens will begin to offer tests. He reaffirmed the importance of ample testing to keep cases of COVID-19 low in the state.

“By learning who has COVID-19, we can isolate those people who are sick, help them recover, and limit the spread of this,” he said.

DeWine added last week that the state was continuing to focus its efforts on limiting the spread in nursing homes, and would be mobilizing the Ohio National Guard to test all staff members in the state’s nursing homes, of which there are more than 960. Montgomery, of Friends Care, confirmed that the guard will be testing at the local facility soon.

Testing is also slated for “minority communities” in the state who are disproportionately affected, according to Ohio Department of Health Dr. Director Amy Acton at a press briefing last week.

“We’re trying to save lives by targeting our most vulnerable populations,” she said.

In addition to these state and county efforts, citizens are still being asked to take measures to keep themselves, and others, safe while the virus is still around.

“We have two big tools in public health — contact tracing and isolation/quarantine — and participation of the community,” Brannen said.

“People following the rules, maintaining social distance, can actually save lives,” he said. “When we see outbreaks arise, it’s because one person was a superspreader and, because they didn’t know how infectious they were, spread it to a lot of people.”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.