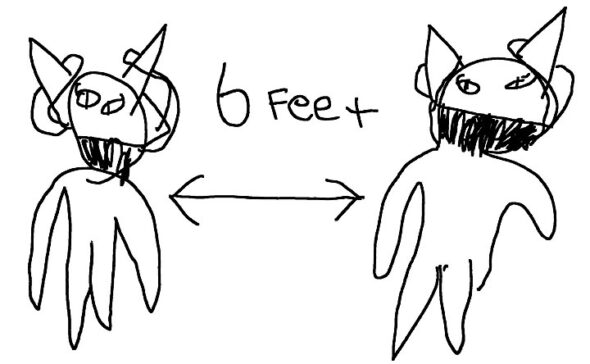

After her father, David Kelley, tested positive for COVID and isolated in their basement, 7-year-old Arabella Kelley put up signs in her home to remind her family how to stay safe: wear your masks and stay six feet apart. (Illustration by Arabella Kelley)

Coming down with COVID— Villagers share virus battles

- Published: February 19, 2021

After receiving two negative rapid tests that same week, Jonina Kelley tested positive for COVID-19 in late December 2020, a few days after her 40th birthday.

It wasn’t altogether surprising — her husband is a healthcare worker who sometimes treats COVID patients. She recovered within a week but worries about the long-term effects of the illness on her body; she still suffers from lingering chest pains and fatigue, and while her sense of taste and smell have returned, they are muted.

“I still don’t feel 100% myself,” she said. “There is just this anxiety.”

Bruce Heckman contracted the novel coronavirus in early January after a visit to a physical therapist’s office, where masks didn’t prevent the transmission in an enclosed office. The 71-year-old turned a corner five days into his illness after getting an infusion of monoclonal antibodies, the same treatment that then-President Donald Trump received in the fall, but not before he feared the worst.

“I thought there was some reasonable chance I was not going to make it,” he said. “It was pretty scary.”

Matthew Collins started writing down all of his account passwords just in case his battle with COVID-19 in early December 2020 took a turn for the worse. The 43-year-old frontline grocery worker spent nine days with extreme fatigue, body aches and coughing, but the anxiety may have been the worst part.

“I was terrified, because perfectly healthy people were dying from it,” he said.

One year into the global coronavirus pandemic, 245 residents of the 45387 area code, which includes Yellow Springs and the surrounding rural area, have contracted the virus. That equates to one out of every 22 people living here.

This week the News spoke with several villagers who were willing to share their experiences with the disease.

Each person’s battle with COVID-19 was unique, with differing symptoms and situations. But in common, they all described the fear and anxiety that accompanied their diagnosis. They all worried about who they might have exposed before they knew they were ill. They all took precautions, but still came down with COVID-19 as its prevalence grew in the area.

And they all came out of the illness with a belief in the importance of continued diligence in preventing its further spread.

“My advice is, you really, really, really don’t want to get this virus,” Heckman said. “It’s that simple.”

‘A lingering sense of anxiousness’

On Saturday, Dec. 6, Matthew Collins woke up feeling groggy and with a headache. By the next day he was also congested and felt a “general malaise.” He called off of work at an area grocery store, to be on the safe side, but he still thought it was just a cold.

“Because I wasn’t running a fever, and didn’t lose my sense of smell or taste,” he said, “I thought it was a cold so I didn’t isolate.”

He arranged a test for that Tuesday, and got the results two days later: COVID-19 positive.

Collins was not alone. At the time, COVID-19 was spreading rapidly in Ohio and Greene County. In the county, average weekly case counts doubled in October, then doubled again in November. They reached their highest level on Dec. 11, when an average of 152 people each day in the county were testing positive.

And while he can’t be sure, Collins believes he most likely caught the virus at work at an area grocery store. As a frontline customer-facing retail worker, his risk of catching the virus was an estimated 20 times higher than the general population, according to a sample study of grocery workers done in the fall.

After the diagnosis, Collins took to a spare bedroom in the house to face the illess. Over the next nine days he dealt with fatigue and a cough. He slept, on some days, five or six hours in the afternoon alone, and also suffered from backaches, stomach aches and general nausea.

“I was completely wiped out,” he said. “It was exhausting to walk across the room.”

Collins took a “cocktail of about six or seven” pills, including vitamin D, C and zinc.

“You start getting a lot of suggestions,” he said of the supplements, which were helpful, at the very least, for their psychosomatic effects.

For Collins, the fear was perhaps the worst part about coming down with COVID, especially since he was, admittedly, already prone to “mass panic.” Early on, when many were still learning what the novel coronavirus was all about, he was stocking up his garage with staple foods.

“You had heard enough stories about healthy people dying,” he said.

As a result, Collins spent some of his time in self-isolation journaling, and documented all of his computer logins and passwords, just in case. In the end, he had to stop reading news about the pandemic, and also put away a book about deep-sea free diving because reading about the extreme activity made him anxious.

“I had to start giving that up. I wasn’t reading the news as much, if at all,” he said.

Then came some more bad news: his wife, Corrie Van Ausdal, tested positive as well. Although young and healthy, she has had some bad bouts with the flu in the past, which concerned Collins.

“You start thinking about the scenarios,” he said. “If the regular flu knocks her out that much, what will this do?”

Spread within a household has been identified as a key method of virus transmission. Greene County Public Health contract tracing found that one-third of all cases come from someone else in the home. That’s on par with a U.S. Centers for Disease Control study tracing 36% of all cases to an infected household member.

Thankfully, Van Ausdal’s only symptom was feeling “a little bit tired.” Although their two children were never tested, Collins assumes they contracted the virus as well, with one running a brief fever and the other just “taking a really long nap one day.”

In the end, Collins was grateful his battle was brief, and that his employer gave him paid leave for the duration of his self-isolation. He also felt lucky to have caught the virus later on during the pandemic, when there was more information about the virus’ course, and possible treatments.

“I felt awful for all of those people who went through what I had to go through with all the uncertainty about the virus,” Collins said.

But the virus’ impact didn’t end immediately. The “mental cloudiness” continued, while it took him three weeks to stop coughing. A sign of the impact on his lungs, his first jog after recovering was brief and frustrating.

“Just running was something I was taking for granted beforehand,” he said.

Reflecting on the experience two months later, Collins sees it as “life-defining.” He feels better, but some things are still there.

“There is a lingering sense of anxiousness and it just doesn’t all go away.”

‘White privilege is part of my experience’

Bruce Heckman did everything he could to avoid contracting the novel coronavirus. As a septuagenarian, he knew the risks were higher of having serious complications from the disease. As a result, he shopped for groceries at Kroger at 6 a.m., and mostly stayed home.

“My wife and I have been about as strict as we can be,” he said. “We’re very, very very careful.”

Heckman thought he would be safe at the office of his physical therapist, who he assumed knew the precautions to take. But upon entering, the therapist closed his office door to separate himself and Heckman from those in the waiting room, unknowingly trapping the virus inside.

“We shut the door to keep the virus out, but we were just closing it in,” he said.

Even though both were wearing masks, and though the therapist additionally had a face shield, the situation wasn’t safe, Heckman believes.

“I was angry,” Heckman recalls. “I gave the office manager an earful about not taking sufficient precautions. Maybe if we had N95s [a medical grade mask with a filter], we would have been okay.”

Although scientists were initially unsure about how the coronavirus spreads in indoor environments, increasing evidence has pointed to the role of aerosols, the tiny airborne particles expelled when a person talks or breathes. In aerosols, the virus can stay in the air for minutes or even hours in poorly ventilated areas, in contrast to larger respiratory droplets from a cough or sneeze, which tend to quickly fall to the ground. It wasn’t until late summer that health agencies started warning the public about the danger of aerosol transmission, which masks can’t necessarily stop.

“It’s not sneezing and coughing on people,” as Heckman explained, “it’s about aerosols, itty-bitty particles.”

A few days later, Heckman got a call from his physical therapist’s office: the therapist had tested positive for COVID-19, even though he was not symptomatic during the appointment. Two days later Heckman got tested. By the third day he had both a positive test result and the start of symptoms. Then, he said, he “descended into the maelstrom of 24 hours.”

“It was something,” he said of being hit with the COVID-19 illness. “I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy.”

Heckman suffered from muscle pains, body aches, a “splitting headache” and loss of appetite. But the worst was the fatigue.

“I felt complete absolute utter depletion,” he said.

Heckman was worried about how he might fare with COVID-19 because of his age. Compared to an 18- to 29-year-old, Heckman’s risk of hospitalization was five times higher and his chance of dying was 90 times higher, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. In Ohio, 26% of all deaths from COVID-19 have been among those in their 70s.

So on his fifth day with the virus, Heckman’s nurse practitioner daughter arranged for him to receive monoclonal antibody treatment at The Ohio State University Medical Center. In early November, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the use of the man-made antibodies in treating patients with a high risk of developing severe COVID-19, such as older adults. It was the same treatment that President Trump received when he was hospitalized with COVID-19.

And, 24 hours after receiving the antibody treatment, just as Heckman was told would happen, his condition improved.

“It was a really dramatic change, and it was clear I was getting better, and not getting worse,” he said.

By his eighth day, Heckman felt back to normal, and soon after came out of his 10-day self-isolation. Four days after that, his wife, Ann, came out of quarantine, a 14-day course to make sure she wasn’t exposed.

In the end, Ann did not get sick, which Heckman was grateful for, pointing to the possible benefit of several standalone UV-light air filters they purchased for their home.

Heckman ended his experience with gratitude. He never had breathing problems, which “would have put the fear of God in me,” he said. His fellow Quakers at the Friends Meeting divided up his clerk duties while he was recovering, while family and friends dropped off food and supplies.

“We had so much food in the refrigerator, we could hardly close the door,” he said.

Heckman also felt lucky to have had access to the antibody treatment. When he received it, he noticed that the other seven patients there at the same time were also white, which he doesn’t think was a coincidence.

“There is no doubt that white privilege is part of my experience,” he said. “I feel really uncomfortable with the fact that other people my age would not have had the chance that I did.”

Black, Indigenous and Latinx/Hispanic people are, compared to whites, at much higher risk of contracting COVID-19, being hospitalized with it, and dying from it. According to data from the CDC, Black people are nearly three times as likely to die from COVID-19 as whites, with access to healthcare as a leading factor.

As Heckman noted about his underlying health, “one of the reasons I’m healthy is I’ve had unlimited access to healthcare my whole life.”

“That comes with being white.”

‘There is a stigma I haven’t been careful’

On Christmas night 2020, David Kelley went to bed early with cold-like symptoms. A healthcare worker who sometimes treats COVID patients at the hospital where he works, he knew his risks, but he also was well aware of the lengths to which his hosptial was going to prevent spread.

For him, staying at home during the pandemic was never an option. His wife, Jonina, was able to work from home for her job with the University of Dayton, but she knows she is lucky.

“Not everybody has the luxury to stay home,” she said.

And even though he still thought he just had a cold, on Dec. 26, David Kelley got a COVID-19 test, in part because he was scheduled to get his first vaccine shot later in the week. The rapid test came back positive, and he self-isolated immediately.

Not surprisingly, healthcare workers are among the most at risk of contracting COVID-19. Although current data is scarce, a study conducted at the start of the pandemic, in April 2020, showed that about 19% of all cases of COVID-19 in the U.S. were among healthcare workers.

While skirting infection for those early months, as community spread increased and hospitalizations rose, David Kelley’s risk increased. In mid-December, Ohio’s hospitals were filling up due to an influx of COVID patients, and 80% of all intensive care units were in use. By Dec. 14, an average of 406 Ohioans were being hospitalized daily for COVID-19.

With her husband self-isolating in the basement, Jonina Kelley then sought testing, all the while caring for their two children upstairs while wearing a mask. On Dec. 27, a rapid test came back negative. But she didn’t feel well the following day, so she got another rapid test, on Dec. 29. That too came back negative.

“I was feeling really tired, but was testing negative,” she said. That evening she recalls feeling fatigued while simply lifting her daughter’s comforter.

Finally, a PCR test also taken on Dec. 29 revealed a truth she was already realizing: she was positive. She was one of 29 people in the 45387 area who tested positive in the week of Dec. 29–Jan. 4, the most since the start of the pandemic.

By then, Jonina said she was feeling “pretty bad,” while David, who only suffered fatigue, was on the mend. Jonina didn’t want to expose her mother, who often helps with childcare, but didn’t have much energy to take care of the children herself.

“The question was, who takes care of the kids?” she said. “We couldn’t send our kids anywhere.”

With David caring for the kids, Jonina mostly rested. She suffered exhaustion, loss of appetite and headache. While she didn’t have any fevers or breathing problems, she was coughing a lot.

At the same time, Jonina was worrying that she and her husband had infected others, including extended family members. She also worried about the kids.

Then, on Jan. 4, both children, ages 7 and 3, tested positive.

“It was scary for them to get tested,” Jonina recalled. “Everyone was nervous.”

Fortunately the kids fared well, with only a few nights of mild fevers. In Jonina’s words, “it never slowed them down.”

Thankfully, other family members tested negative. And because the Kelleys were on break for the holidays, they didn’t spread the virus at school or work.

“No one else did end up getting sick, it was just our family,” she said. “The timing was lucky.”

Even though they are pretty sure they didn’t spread it to others, Jonina feels there is still a stigma to a positive COVID-19 diagnosis.

“I feel like I have to say I got it from my frontline worker, otherwise there is a stigma that I haven’t been careful or that we’ve been reckless,” she said.

Several people this reporter asked to be interviewed about their experience with COVID pointed to the same factor in declining to be interviewed.

A little more than a week after she fell ill, Jonina started to feel better. Strangely, it was at the tail end of the illness that she lost her sense of taste and smell completely. It took her 10 days to get it mostly back, but it’s still not what it used to be. Her doctor prescribed her a steroid inhaler to help her “clear out her lungs” but chest pains continue. She is also still suffering from fatigue.

“I’ve been concerned I was going to have long-term effects,” she said.

As Kelley, Heckman and Collins recover, cases are finally falling in the area. In Greene County, cases are down more than 50% since their peak in mid-January. But they remain three times as high as cases were in the summer. Moreover, herd immunity is still a long way off, as less than 10% of state and county residents have received their first vaccine dose, well below estimates that 75–80% is needed.

Those who have had COVID-19 want those who haven’t to understand the importance of avoiding it if they can. Wearing a mask, staying home as much as possible, avoiding large gatherings and not spending time indoors in close proximity to others all remain important, they believe.

As Heckman put it, “quit your bellyaching about masks, and just do it.”

2 Responses to “Coming down with COVID— Villagers share virus battles”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

*How long immunity actually lasts is still unknown.

Ideally, all people within individual households probably should have been included in vaccination efforts for the whole family so that someone having the vaccine doesn’t unwittingly infect a loved one while exercising his/her “new found freedom” by mingling more under a perceived post vaccine “security net.” Also, the way it is the effectiveness of the vaccine for various family members may dissipate at various times and be difficult for families to track. There isn’t enough said about the problems inherent with the current roll out method. PLEASE continue to practice ALL safety protocols to protect yourself and others. (This issue is another example of pitfalls of limited vaccine supply.)