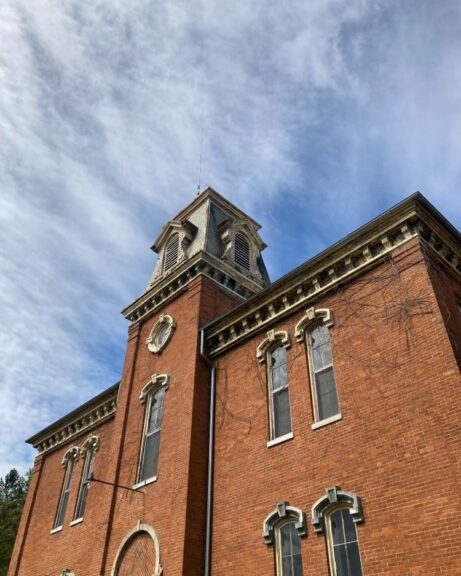

From late-summer through mid-autumn, chimney swifts migrate to much of the eastern part of the United States — including Yellow Springs. During this time, these swifts tend to congregate en masse around the chimney of the Union School House, among a couple other tall hollow structures around the village. (Photo by Reilly Dixon)

Tin Can Economy — A space in the school for the swifts

- Published: August 19, 2021

Walk over to the Union School House on a clear late summer evening and you’ll see them. Swooping and darting through the dusk, conducting aerial dramas against the backdrop of a setting sun: chimney swifts. Hundreds of them.

Whizzing around the stately mansard tower of the schoolhouse and diving into the adjacent chimney, these cigar-shaped birds really know how to put on a show. Crane your neck one night and watch for yourself. Almost masquerading as bats, the tittering swifts will be feasting on airborne bugs, charming mates with flights of fancy and torpedoing in and out of the tower where they’ve made their nests.

From about mid-August through mid-autumn, chimney swifts call our neck of the woods home. They’ve traveled all the way from South America to the eastern half of the U.S. for breeding season, all in search of a suitable high-up hidey-hole to start a family. And if you’re a swift, the rust belt makes for decent real estate. Abandoned towers, crumbling edifices, busted-out smokestacks — all prime homes for these birds.

Here in Yellow Springs, chimney swifts mostly seem to congregate around the schoolhouse, the tower at Millworks, the old Antioch power plant and even around Mills Lawn.

They’re charming little birds, chimney swifts. They spend the majority of their lives on the wing — foraging, bathing, drinking and occasionally mating, all in the air at breakneck speeds. While chimney swifts typically fly close by their namesake structures, they’ve been seen to cover vast swaths of the sky. A World War II pilot once reported seeing a swift dozing mid-air nearly a mile above Earth’s surface. They can travel up to 500 miles in a single flight. And unlike most other birds, they are incapable of perching. Instead, they cling vertically to rough surfaces.

They’re charming little birds, chimney swifts. They spend the majority of their lives on the wing — foraging, bathing, drinking and occasionally mating, all in the air at breakneck speeds. While chimney swifts typically fly close by their namesake structures, they’ve been seen to cover vast swaths of the sky. A World War II pilot once reported seeing a swift dozing mid-air nearly a mile above Earth’s surface. They can travel up to 500 miles in a single flight. And unlike most other birds, they are incapable of perching. Instead, they cling vertically to rough surfaces.

Beyond being just fascinating creatures, swifts prove themselves to be quite useful to humans. A single swift can eat thousands upon thousands of disease-carrying mosquitoes, flies, termites and other insects each day.

You know where this is going; you’ve heard it before.

Chimney swifts are becoming increasingly endangered. In 2010, the International Union for Conservation of Nature changed the chimney swift’s status from least concern to near threatened. Eight years later, the same organization changed the bird’s status to vulnerable. These status changes come on the heels of a precipitous decline in population over the last half-century. The North American Breeding Bird Survey estimates a cumulative decline of over 70% since 1966.

And given that 99% of all chimney swifts in the world mate in the U.S., this isn’t a problem whose fault we can outsource.

Why is this happening? Where are the swifts going?

Intuition offers an easy answer: there are simply fewer chimneys on our buildings. But this is only part of the story. Existing chimneys are being demolished or renovated out of existence. Caps are put on residential chimney tops. All of these actions displace swifts — who, it should be said, pose no structural harm to our built environments.

On a larger scale, the problem becomes more troubling. Like everything else, swifts are ensnared in an ecological web facing calamity. Old growth forests, another opportune habitat for swifts, are being logged all up and down the continent. Hurricanes — whose intensities have grown in the worsening climate catastrophe — have wiped migrating flocks off the map entirely. Pernicious temperatures alter habitats altogether.

Let’s return, then, to the Union School House.

As unveiled at a Planning Commission meeting last month, 91.3 FM WYSO will be moving its operations into the Union Schoolhouse in the near future. The historic building will be developed to accommodate all WYSO’s goings-on: broadcasting, programming, hosting events and so on.

According to Max Crome, the architect on the project, construction will wrap up not long after the schoolhouse’s 150th birthday sometime next year.

Renovation plans are extensive. They include removing a number of the interior walls and some flooring to open up the space within the existing building. A 10,000-square-foot addition will be tacked onto the property’s west facade. In the interest of beaming in natural light into the existing structure, the chimney (not the front-facing tower) will be replaced by a skylight that will illuminate the interior, from the top story to the basement.

It’s a neat idea. I’m charmed that my favorite radio station will be housed in my favorite building in the village. Moreover, I’m attracted to Crome’s interest in retaining the historic aesthetics of a building desperately in need of preservation. Even as an immediate neighbor to the schoolhouse, I’m not that daunted by having a livelier building on the block.

I am, however, concerned about the swifts.

The removal of the chimney to make room for a skylight — while an architecturally compelling move — is a threat to the hundreds, if not thousands of swifts. Its demolition will serve to displace an already threatened population, thereby continuing a dismal trend that tends toward an eventual extinction — yet another on a growing list.

And to pan the camera out a little bit: with the old Antioch power plant being slated for demolition, presuming its large tower is included, I worry Yellow Springs may soon no longer be a destination for swifts at all. We may become just another fly-over town.

The Union School House as it appears on the Dayton Street side. (Photo by Reilly Dixon)

Somewhere in all of this is an object lesson.

Swifts and humans are far from alike. One conducts their affairs in the skies, the other on the ground. One has wings, the other could only dream as much. But what might our similarities be?

Both we and the swifts are thrust into the world, destined to adapt or perish. Pressed by the conditions of existence, we both opt to adapt. We carve out our niches, our nests where we can.

We become the places we inhabit and absorb their qualities. We are defined by our spaces — they structure our limitations and give dimension to our possibilities. Just as we learn to manufacture concrete, a bird learns to cling to it. And somewhere amid all our smoke and cement, those little flying cigars made a habitat.

I wouldn’t call this symbiosis, per se — I think chimney swifts would manage just fine without us and our designs. Rather, what these magnificent birds have to offer us is a lesson in cohabitation.

They asked no quarter of us, and yet we inadvertently gave them some.

We manufactured a relationship with swifts — albeit unwittingly. But as such, we ought to feel called to nurture and protect that relationship. If we are to be stewards of our spaces, then we must provide for all their constituent members. We must understand that no space is truly vacant. No space is uninhabited or a tabula rasa ripe for development.

Thus a contingency plan to protect the Union School House chimney swifts must be implemented before construction on the property begins.

If the chimney is to be demolished, we must first provide the swifts with an alternate habitat, perhaps several. This may take the form of one or more free-standing swift towers — hollow structures at least 12´ tall, built for the sole purpose of housing the endangered birds.

A cursory Google search of “chimney swift towers” not only yields a smattering of blueprints for said towers, but also a number of articles on communities across the country that have successfully funded and built these structures.

Why stop with the schoolhouse?

There are a number of Village-owned areas that would make splendid sites for swift towers. They could be designed, constructed and painted by local makers and artists. Muralists could collaborate with students in painting the towers. In the end, each tower could be a community gathering place to learn about chimney swifts, other local wildlife and conservation more generally.

If these projects sound at all appealing, and you’d like to work in the interest of protecting a threatened member of our local ecology, I would be delighted to hear from you. Perhaps together we can continue sharing our village and the spaces therein with the chimney swifts.

*Tin Can Economy is an occasional column that reflects on object, form and scale. It considers the places and spaces we inhabit, their constituent materials and our relationship to it all. Its author, Reilly Dixon, is a member of the Environmental Commission. Contact Dixon at rdixon@ysnews.com.

2 Responses to “Tin Can Economy — A space in the school for the swifts”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

We live next door to the schoolhouse, and we too, have a chimney. Every morning I sit next to our fireplace, writing in mediation, and part of my meditation is listening to the charming birds in our chimney. The charming sounds I hear seem to be from a mother bird feeding her nestlings, and it’s adorable. I actually do not know exactly what birds I’ve been eavesdropping on, but now, I’m just going to presume that they’re swifts…

Thank you for the information!

Is it possible to acquire some environmental grant to build relocation towers for the swifts to inhabit? As part of the Yellow Springs landscape, they are, our neighbors, feathers and all. They might come to represent a meaningful symbol for villagers of preservation and endurance. Thank you for reporting on this.