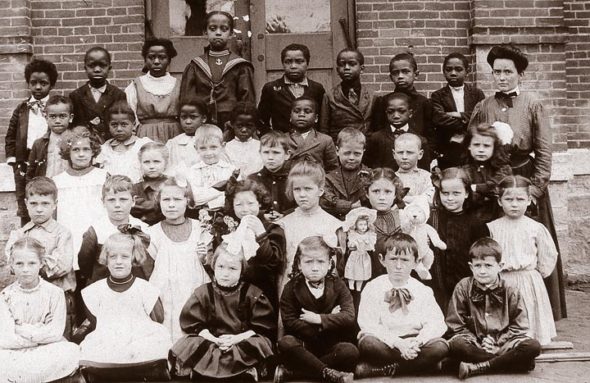

Yellow Springs schoolchildren were photographed in 1905 on the steps of the Union School House after a state law requiring segregated schools was struck down. The “Blacks in Yellow Springs” encyclopedia includes an entry on the village’s rich tradition of black leadership in local schools. (Submitted photo courtesy of Yellow Springs Historical Society)

A people’s history of Yellow Springs

- Published: February 22, 2018

Eliza and Dunmore Gwinn. Joe Curl. Lewis Adams. Jefferson Williams. The Gudgel family. Jim Felder. Alyce Earl Jenkins. The names are a roll call of Yellow Springs, past and present.

About 50 and counting local residents, whose lives span three centuries, are represented in an ambitious effort to create a social history, a people’s history, of African Americans in Yellow Springs. Organized by The 365 Project, and spearheaded by local educator John Gudgel and Antioch College Assistant Professor of History Kevin McGruder, the effort takes the form of an encyclopedia, titled “Blacks in Yellow Springs.” The group’s encyclopedia initiative launched in late 2016, and has gained momentum — and entries — since then.

“There’s a rich history in Yellow Springs that is in danger of being lost,” Gudgel said recently. “Our elders are passing on, and these stories will pass on with them.”

Gudgel should know. Born and raised in Yellow Springs, he returned here after college to teach in village schools. His local roots go back to the late 1800s, when the families of both his mother and father came to Yellow Springs, seeking relief from the “harshness” of racism in the South, he explained. He still remembers going to vote with his grandmother at the fire station on Corry Street. The year was 1960, Gudgel was just a kid, and his grandmother dressed to the nines to perform that civic duty.

“It was a tradition from the South,” Gudgel said. “For black people, the right to vote was an honored, cherished thing. So you dressed up.”

McGruder is a relative newcomer to town, moving here in 2012 to teach at Antioch. But he’s active in Central Chapel A.M.E. and other village institutions, and this project, according to Gudgel, is McGruder’s “brainchild.”

“I’m learning Yellow Springs history as I go along,” McGruder said, with a laugh. “There’s so much I don’t know.”

Stories, and memories

Enter three women who do know: Phyllis Jackson, Isabel Newman and Karen McKee, members of the encyclopedia committee, which also includes William Simpson and Joe Lewis. All three women have written multiple entries for the encyclopedia, as has McKee’s sister, Jean, in some cases based on their first-hand knowledge.

Antioch baseball coach and youth sports organizer Joe Curl is one of dozens of historical figures, as well as current residents, included in the “Blacks in Yellow Springs” encyclopedia. (Photo by Axel Banhsen; courtesy of Scott Sanders, Antiochiana)

For example, Jackson, who is 93 and a fifth-generation Yellow Springer, remembers Joe Curl, who coached Antioch’s baseball team — “the Yankees of Southern Ohio” — at the turn of the 20th century. Curl was also a custodial worker at the college. In 2015, Antioch renamed its East Gym “Curl Gymnasium” in his honor. Curl lived a block from where Jackson grew up, and she recalls him as a “strict disciplinarian” who introduced young men to the sports of baseball, boxing, golf and tennis, providing gear and instruction to those who otherwise wouldn’t have had such luxuries.

“He was an outstanding man in my community,” Jackson said. And she even remembers his bulldog, a rather fearsome-looking dog to her as a young girl, lying in the sun at the corner of High and Limestone streets, waiting for Curl to come home.

“I’d tiptoe across the street so as not to disturb that dog,” Jackson chuckled.

The encyclopedia, currently available online at the365projectys.org, has an entry on Curl, written by Jackson, who has also written or is working on a dozen other entries, including of family members such as James Lawson, her brother and a former Yellow Springs mayor.

Another figure Jackson reminisced about recently is Mae Wing, whom she remembers as “a very sweet woman” who would sew dresses for local girls who didn’t have a nice dress to wear on their first day of school. Wing had a stock of old clothes, which she’d take apart and sew up into new clothes, Jackson said.

“She’d remake a dress and hang it on their door to surprise them on the first day of school,” Jackson explained.

Wing’s concept inspired a Yellow Springs shop, called the Goods Exchange, opened by Wing and fellow seamstress Georgia Pettiford. The exchange offered villagers clothes remade from old garments, according to Jackson.

Isabel Newman, also in her 90s with Yellow Springs roots going back to the Gwinns, some of the village’s earliest black residents, likewise has personal connections to several of the individuals she’s profiling in the encyclopedia. For example, she composed an entry about her father, Lewis Adams, a Village Council member who authored the 1947 Yellow Springs Accommodations Ordinance, which “outlawed racial segregation and discrimination in public places in Yellow Springs,” according to Newman in her entry on Adams. Recently, she learned that he was involved in actually bringing lawsuits against some local businesses that discriminated based on race, despite opposition from some local whites to that step. She’s revising the entry — and her sense of personal history — in light of that new information.

“I found out why I’ve been so radical my whole life,” Newman exclaimed.

Newman also wrote an entry about a figure of quieter influence, Mrs. Harris, who operated a nursery for “colored children” in town during the 1920s. Newman herself didn’t know Mrs. Harris, but she said she admires what she’s learned about the woman’s ability to make a little go a long way to serve Yellow Springs’ youngest black children.

“The nursery school was not rich enough to afford toys but her babies, as she often referred to them, discovered that a large wooden box … made a delightful play house … under the careful guidance of Mrs. Harris,” Newman’s entry reads.

Update of earlier effort

The “Blacks in Yellow Springs” project grew out of an earlier 365 Project effort, in 2016, to update a brochure on black life in Yellow Springs that was originally created by a former Antioch professor, G. Jahwara Giddings, and his students in 2006. The updated pamphlet, done in collaboration with the Yellow Springs Chamber of Commerce, was a worthy project — but not enough, according to Gudgel.

“People kept pointing out, this isn’t there, that isn’t there,” he said. “We had to look at another way to bring all the history together.”

So the encyclopedia committee was formed to identify people, topics and potential contributors. The first submission deadline was set, around this time last year, with several additional deadlines since then. Contributors are “ordinary folks” writing about their families, their friends, their heroes and sometimes even themselves, according to McGruder, who is planning to contribute a synthesis of the civil rights era in Yellow Springs and an entry specifically about racism in the village.

Some contributors are reluctant to write about racism and discrimination explicitly in their entries, out of decorum or the complex social realities of living in a small town, he explained.

“There are so many anecdotes that come out during conversation that aren’t things people would write down,” he said of local experiences of racism. “The intent isn’t to indict Yellow Springs, but to place the experiences of black people in context.”

The risk of not writing about racism in some form is “people thinking everything’s perfect in Yellow Springs,” he added.

And in fact, a separate initiative, called “Reflections on Race,” invites villagers, black and white, to share their recollections about racial issues in Yellow Springs. Some reflections have already been posted at the 365 Project website.

“It fits with The 365 Project’s mission of encouraging courageous conversations,” McGruder said.

Meanwhile, the online encyclopedia is being updated as new submissions come in. There will, eventually, be a printed version. But that’s down the road, according to McGruder, who wants to make sure the encyclopedia is reasonably comprehensive before anything’s committed to print.

In addition to individuals, “Blacks in Yellow Springs” is covering events, organizations and black businesses. Karen McKee is leading the effort to identify, research and characterize black businesses in town, of which there once were dozens. The online encyclopedia now lists more than 40, ranging from shoe repair to catering to plumbing to legal services to the large-scale building and contracting enterprise of Omar Robinson, creator of a development of about 60 homes built in the 1950s and 60s. Businesses currently represented span the 1920s to the early 2000s. Today, virtually none remain.

The loss of black businesses in Yellow Springs in recent decades likely relates to many factors, according to McKee.

“The decline in Black owned businesses was due in part to desegregation, fewer African Americans living in the village, and the high cost of conducting business in YS, especially when you do not own property,” she wrote in an email.

Loss is one dimension of — and impetus for — the project, according to Jackson and others. Asked about the significance of the encyclopedia, Jackson said, “At the rate that blacks are leaving Yellow Springs, soon Yellow Springs will be a white community and all that history will be gone. … People need to know that blacks were here.”

Newman agreed. “The black population has dropped in Yellow Springs,” she said. “And people aren’t aware of the contributions of blacks to the community.”

The population of African Americans in the village is down to under 15 percent from a high, in the 1970s, of 27 percent, according to previous News reporting.

Pointing forward

But the encyclopedia project also points forward. Related to the effort, The 365 Project has organized a program of “Blacks in Yellow Springs” walking tours with youth tour guides, including tours specific to places of worship and black businesses. And both projects are inspiring local history learning in Yellow Springs schools.

For example, Mikasa Simms’ first-grade class is currently wrapping up a project-based learning, or PBL, project on “hidden figures” in local African-American history. First-graders interviewed 14 local African-American “change-makers”: Isabel Newman, Pastor Bill Randolph, Gerry Simms, William Simpson, Basim Blunt, Julia Davis, Lillian Slaughter, Phyllis Jackson, Alfred Pierce, Sterling Wright, Kelley Fox, Dr. Kevin McGruder, Dr. John Fleming and Betty Ford. Photos of those individuals and videos the students created will be part of a new “YS Hall of Fame,” to be unveiled Feb. 21 at Mills Lawn, according to Simms.

“They were so excited! They got to use special recorders and they wore their ‘smart clothes’ for the day,” she wrote in a recent email about the project. Students watched kids interviewing former President Barack Obama for interviewing tips, she added.

And every day during February, Black History Month, Mills Lawn is featuring a local African American who has had an impact on Yellow Springs, according to Gudgel.

“They’re learning about all the social and oral history that’s tied to today,” he said, ticking off names like Wheeling Gaunt, Joe Curl and Donald Perry, founder of the Perry League, Yellow Springs’ beloved T-ball league. “It blows their minds.”

Villagers who wish to learn more about the project or contribute material to the encyclopedia can contact organizers at the365projectys@gmail.com or The 365 Project, P.O. Box 165, Yellow Springs, OH 45387. The next submission deadline is Friday, March 30.

4 Responses to “A people’s history of Yellow Springs”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

I wish to report an error regarding the name of the wife of Rev. Richard Phillips who is included in the 365projectys. He was a Baptist Church pastor in Yellow Springs for years. His wife’s name was Gwendolyn, not Gladys as listed. His daughter continues to live in the Cincinnati area and can validate her mother’s name as Gwendolyn Baker Phillips. I would like to purchase a copy of the Encyclopedia once this correction has been made to the Community Encyclopedia. Reva Hutchins/(614) 235-8791 – My mother was married to her brother, Oscar Baker). Thank you for this wonderful Encyclopedia!

I knew Omar Robinson as a teenager when I worked on many of his project houses with my father who owned Johnson Electric, Plbg & heating in Xenia., years before I moved to YS. Another black individual with YS roots, is my daughter, Cyraina, who graduated from Mills Lawn, and has been a book author and Professor of Black History at Notre Dame for many years.

I hadn’t heard the name Omar Robinson for many years. My father, a painting contractor, worked on Omar’s projects when I was a child.

I know this article is from 2018, however, how is there no mention of the Hamilton, Benning or Cordell families. My grandfather Harold Hamilton Sr laid and knew where every undergound pipe and electric pole is in yellow springs. How about doing an article on the history of our families? Thank you