Pollution continues in Glen waters

- Published: February 1, 2018

On Nov. 6, 2017, the village was pounded by torrential rains. The rainwater — around 3.75 inches over a 24-hour period — poured over yards, down streets and through farm fields, emptying into Village storm sewers and local creeks and eventually into the Glen Helen Nature Preserve.

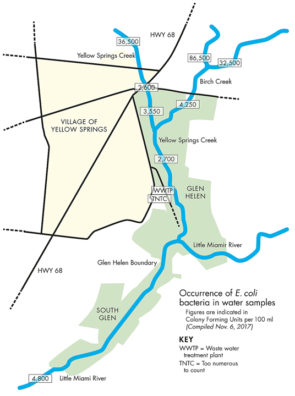

At several points on its journey to the Little Miami River in the Glen, where all the water in our watershed drains, the water tested high for E. coli and nitrates, pollutants that can harm local wildlife as well as people and animals who come into contact with the water.

Although November’s rain event was exceptional and its ecosystem impact dramatic, it highlights year-round concerns for water quality. How clean are the creeks, rivers and springs of Glen Helen? How does local water quality affect the Glen’s ecosystem, and vice versa? And what can villagers do to improve the watershed to protect the Glen and all those living downstream?

Those are a few questions Audrey McGowin, a Wright State University environmental chemist and Fairborn resident, has been exploring through her seven-year study of water quality in and around Glen Helen.

Each fall since 2011, McGowin has led students of Advanced Environmental Chemistry in sampling and testing water at 12 points in Yellow Springs Creek, Birch Creek and the Little Miami River, along with area wells and springs.

McGowin’s conclusion: While the water leaves the Glen far cleaner than when it enters, water contamination is a threat to the ecology of the Glen and those who come in contact with it, she said. It’s a message she hopes will spur locals to act to protect their watershed.

“My main message is that storm water runoff carries with it all the things that we dump on the ground and in the streets — that what we do personally affects the water in the streams,” McGowin said.

Glen Helen Ecology Institute Executive Director Nick Boutis echoed McGowin’s conclusions about water quality in the Glen. He said the Glen is performing a vital ecosystem service for the village and all points downstream, but is not immune to damage.

“We rely on natural areas to take what we’re giving it and make it cleaner because the environment has the capacity to absorb pollutants,” Boutis explained.

“By the same token it’s worth reflecting on the fact we send a lot of crap into our natural areas … runoff from fertilizer, pesticides, insecticides, not-fully-treated sewage and litter,” Boutis said. “We can do something about that.”

Summary of pollution concerns

Just how bad was the water during the November rainstorm, and what about the rest of the year?

On Nov. 6, E. coli colony counts were more than 200 times the Ohio EPA’s primary contact limit in Birch Creek and near the Village’s wastewater treatment plant and 100 times the limit in Yellow Springs Creek. Bodies of water measuring over the primary contact limit are not suitable for full body contact activities such as wading, swimming or canoeing, according to the Ohio EPA. Nitrates were so high that day that McGowin estimated that seven tons of nitrogen in the form of nitrate and ammonia washed from the Birch Creek and Yellow Springs Creek watersheds during the rain storm.

But even at other times of the year, E. coli is a problem in several Glen springs and south of the wastewater treatment plant, which does not treat wastewater with chlorine during the six months of the year considered winter by the Ohio EPA, according to McGowin’s research. And McGowin and her students have measured levels of nitrates in area private wells that are well above acceptable levels.

The source of the much of the pollution McGowin and her students have found is fertilizers and animal and human wastes. Although the agricultural area north of town — including cattle operations and conventional corn and soybean farming — is of concern, McGowin was hesitant to ascribe blame to a single source.

“We’re seeing a lot of runoff contaminants that could be from agricultural activities, but my goal isn’t to browbeat farmers, it’s to get everyone to understand how their behaviors affect the quality of their water and the Glen,” McGowin said, noting the location of the Village’s municipal well field near the Little Miami south of the Glen. Villagers also contribute to the pollution by not picking up pet waste in their yard, fertilizing their lawns and washing their cars in their driveways, she added.

On the threats to hikers in the Glen, Boutis said that none of the 30 springs found so far in the Glen have tested safe for drinking and that wading in streams both damages aquatic ecosystems and increases the chances that the people and pets who do so may get sick.

The Yellow Spring is the only spring in the Glen tested that was “not found to be unsafe,” Boutis said. But the colorful sediment at the spring should not be used to paint one’s face or body since McGowin and her students have found it to be naturally high in heavy metals such as arsenic and cadmium and to contain some lead.

As for swimming in Birch Creek below the waterfall, Boutis simply said, “if they knew what I did about the water that comes into the Glen, they wouldn’t be in there.”

Though research conclusions from McGowin’s class have helped the Glen advise the public on how to be safe while visiting, the larger problem of watershed pollution is more challenging, according to Boutis.

“What [McGowin] and her students have accomplished has not only given us a much better sense of the ecology of the Glen, it has helped us identify our priorities and how to protect the public,” Boutis said. “The things that are harder for us to tackle include what we can do about water rushing off of area property owners yards — that’s the non-point source challenge.”

The dangers of E. coli

Much of McGowin’s classes’ research has focused on the two primary contaminants — E. coli and nitrates. Both from agriculture, their presence in area creeks is not altogether surprising, yet they can be a threat to ecosystems and people.

E. coli is a fecal chloroform bacteria from human and animal wastes that can cause gastrointestinal illness from swimming in or drinking water containing high counts of it, according to the Ohio EPA. While not all strains of E. coli are dangerous, with high numbers of colonies the likelihood increases, McGowin explained.

McGowin and her students have also found E. coli in several springs in the Glen in recent years, including the Traveler’s Spring, which bubbles up from the ground near the Pine Forest, and the Dairy Spring along Grinnell Road between Corry Street and the wastewater treatment plant. The class has never found E. coli in the Yellow Spring.

The Ohio EPA’s primary contact limit for E. coli is 410 colony forming units (CFUs) per 100 ml. On Nov. 6, E. coli per 100 ml measured 36,500 CFUs at Yellow Springs Creek headwaters near Ellis Park, 86,500 CFUs on the north branch of Birch Creek north of State Route 343, 32,500 CFUs on the east branch of Birch Creek and “too numerous to count” near the Village’s wastewater treatment plant, which indicates a reading of at least 100,000 CFUs per 100 ml.

McGowin speculated that cattle operations north and west of the village could be responsible for high E. coli counts in Yellow Springs Creek and Birch Creek, along with possible leaking septic tanks from area homes. The east branch of Birch Creek collects runoff from a small residential area along Meredith Road.

As for the wastewater treatment plant, Village Wastewater Superintendent Brad Ault confirmed this week that the Village does not add chlorine, which kills E. coli, to its treated wastewater between Nov. 1 and April 30 since it is not required to do so by the Ohio EPA.

“The theory from the EPA is that people are not in the stream at that time,” Ault explained. “We don’t run tests for E. coli but there is going to be E. coli in the water [during those months.]”

However, because many people visit the Glen in the winter, Boutis is concerned about possible E. coli contact in the south Glen. The wastewater treatment plant releases its effluent into Yellow Springs Creek in the Glen along Grinnell Road a few thousand feet north of its confluence with the Little Miami River near the covered bridge.

“The EPA doesn’t expect people to be recreating in the water in the winter but people use the Glen year-round,” Boutis said. “It may make sense given people’s behavior that we look to extend our chemical treatment of effluent through more of the year.”

But Ault said that adding chlorine to treated wastewater year-round wouldn’t make much of an impact, as most of the E. coli in Yellow Springs Creek are likely from agricultural sources further upstream. Moreover, the quantity of water released from the wastewater treatment plant — about 400,000 gallons per day — is relatively small compared to the volume of the river, he said.

The Village only exceeded its EPA permit level for E. coli on three occasions last year, two of which were during high rains and another which Ault believes was an erroneous reading. The Village is only required to test for E. coli from May 1 to Oct. 31. In recent years, EPA violations have dwindled thanks to the new plant built in 2010, which has an overflow pond to treat more water during heavy rains, Ault added.

Furthermore, Ault stressed that the groundwater that is the source of the Village’s water is under little influence from the nearby Little Miami River, though he didn’t rule out that some mixing may take place. To protect local water quality, the Village “takes its job very seriously,” he added.

“We do everything we can do to treat the wastewater,” Ault said. “There are issues that arise that are out of our control and we try to fix them and prevent them in the future.”

Nitrate concerns

Also concerning to McGowin were high nitrate levels in surface water and area wells. McGowin and her students tested for various forms of nitrogen, ammonia and ammonium, the source of which could be either manure or fertilizers.

Nitrate is found in creeks year-round even when there has been no rain for several days, leading McGowin to conclude that it is coming from groundwater sources. Four residential wells out of more than a dozen tested confidentially in the area surrounding the Glen as part of the study contained nitrate-nitrogen levels above the EPA drinking water standard of 10 milligrams per Liter, including one well with nearly twice the limit. Water containing those levels of nitrate should be treated before it is used for drinking or cooking, McGowin advised.

High levels of nitrates in drinking water can be dangerous to infants and small children, who can develop life-threatening methemoglobinemia, also known as “blue baby syndrome,” according to Mark Issacson, program manager for Greene County Public Health. However, he rarely sees nitrate contamination in county well tests and has never seen a case of methemoglobinemia in his 31 years at the health department.

More commonly, about 20 percent of the time, a well tests positive for E. coli, Isaacson said. He added that shallow water sources such as springs or dug water sources are far more susceptible to contamination. Nitrate pollution, which often peaks in the spring, could also indicate highly permeable soil, he said.

“When they break down, nitrates can travel fairly rapidly through the soil, so if you have nitrates in our water, you may want to get it tested for other things,” Isaacson said. He recommended that well owners should test their wells regularly, which can be done through Greene County Public Health.

In addition to human health concerns, nitrates and other nitrogen compounds can cause harmful algal blooms in bodies of water that decimate aquatic life by depleting oxygen in the water. McGowin said she has seen algal blooms in rivers in the Glen, and their presence is documented all the way downstream to the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. McGowin said her Nov. 6 calculation of nitrogen runoff from 7,000 acres of seven tons — a weight equivalent to a school bus — was actually a conservative estimate, and speaks to a larger ecological problem.

“That’s one rain event and two little watersheds, so you can see why the dead zone in the Gulf is as big as New Jersey,” she said.

Cleaning up our act

Villagers can take steps to help clean up local waters. Wise fertilizer use is important, since applying too much or applying right before a rain means large quantities of nitrates end up in the Glen, Boutis said. In addition, people should consider how their actions have a cumulative effect. While one resident leaving their dog’s poop on their lawn might not seem concerning, with hundreds of dogs in town, the waste adds up, he said.

The Glen’s purchase last year of the Village-owned Sutton Farm just north of the Glen across State Route 343, through which Birch Creek flows, will also help reduce agricultural pollutants from entering the Glen, Boutis said. The 76-acre farm will no longer be conventionally farmed. Instead, invasive species will be removed and efforts will be made to slow water flowing into and through the stream so the ecosystem can remove more contaminants. It’s a first step to improving water quality before it even enters the Glen.

“We’re starting to ask what can we do to protect more land and work with land owners on this,” Boutis said.

McGowin suggests partnerships with area farmers to address farm runoff, but also encourages villagers to look at their landscaping habits.

To McGowin, the Glen has been an ideal study site for an environmental scientist, with its clear inputs and outputs. But the Glen is also “a special place that needs to be protected” she urged.

“The Glen is a gem and if we want to keep it, we have to think about protecting because it is at risk,” she said. “The impacts of climate change will be hard enough on Glen Helen without adding to its woes.”

Looking to the Glen’s future, Boutis finds the nature preserve to be both fragile and resilient in the face of ecological threats.

“There are elements of fragility and resilience in every natural area and both of those dynamics live in the Glen,” Boutis said. While visitors over the course of a weekend could trample natural areas and widen trails, after huge deluges of rain that wash away hillsides, the wildflowers still come up in the spring, he said.

“You get these examples of resilience that are equally powerful.”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.