In April, staff at Friends Care Community received a donation of handmade face masks from the YS Chapter of Days for Girls. Pictured in masks, left to right: Bethany Miller, director of social services; Sheila Bratchette, director of rehabilitation; Angie Hendricks, PTA; Melissa Herald, nurse manager; and Hannah Moorman, director of nursing. (Submitted Photo)

2020 Year in Review: Top Stories

- Published: January 6, 2021

The pandemic reaches YS

In mid-March, the threat of the novel coronavirus prompted swift and drastic actions from the state government, affecting daily life in the village.

Local institutions responded to government orders and acted proactively to limit the ways that villagers come in contact with one another to reduce the spread of the virus. Starting on Wednesday, March 11, and continuing through the next week, nearly every community event was canceled and public space closed.

Local K–12 schools, the Wellness Center, the Little Art Theatre, local restaurant dining rooms and Glen Helen closed. Antioch College’s campus, the Yellow Springs Library and most retail shops also closed; grocery stores, pharmacies and banks remained open. Learning moved online for schools. Friends Care Community closed to visitors. The primary election, set to take place on Tuesday, March 17, was postponed hours before voting was to begin.

Yellow Springers were stocking up and staying home as the impact of the global COVID-19 outbreak started to be felt here, even without a confirmed local case of the disease.

Almost immediately, villagers and local institutions stepped up. The Yellow Springs Community Foundation assembled a team to focus on food security and financial assistance to hurting community members and set up a fund to handle donations. Tom’s Market and the Senior Center partnered to deliver groceries to hundreds of local senior households. The local school district figured out ways to get food to families in need. The Village began hosting “virtual town halls.”

From March 23 through the end of April, Ohioans were under a “Stay at Home” order, during which residents were only permitted to leave their homes for essential activities.

On April 9, the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in the village. Matthew Huntington, 50, who suspected he contracted the disease at his job at a Columbus call center, fell ill around March 22. On April 5, he was transported from his home in the village to Soin Medical Center in Beavercreek. When his condition worsened, he was moved into the intensive care unit and put on a ventilator.

Then, on April 22, came tragic news. Huntington died after battling the disease for more than two weeks in the hospital. The Yellow Springs High School graduate was best known locally as a musician and as an avid player of bridge and Dungeons and Dragons. He played the bass clarinet in the Yellow Springs Community Band and Community Orchestra, and regularly played bridge at the Yellow Springs Senior Center.

Huntington’s death was the third in the county from the disease. He is the fourth youngest person to die from COVID-19 in Greene County.

Starting in May, Yellow Springs gradually opened up with the rest of Ohio. That led to a midsummer spike of cases, which began moderating by August. Eight local cases were confirmed by mid-August.

Beginning in late August and continuing through the end of the year, cases took off in the village, county and state. While the county was adding 10 to 15 new cases per day in August, by mid-December, it was up to 150 new cases per day. Starting on Oct. 15, Greene County was designated “red,” indicating “very high exposure and spread” here. By Dec. 27, Greene County had recorded 9,246 cases, 487 hospitalizations and 109 deaths. In the 45387 area code, cases nearly tripled over a six-week period, growing from 52 on Nov. 5 to 163 on Dec. 27.

Clusters of cases began to appear in the village, prompting restaurants to temporarily shutter, high school basketball games to be canceled and the Miami Township fire station to be down to bare bones personnel. Meanwhile, a local institution serving some of the area’s most vulnerable residents, Friends Care Community, remained without any confirmed cases of the virus among residents and just two among staff since the start of the pandemic.

By year’s end, vaccines were beginning to be rolled out in the state, but the virus, nevertheless, continued to spread. In the final weeks of the year, the Yellow Springs Community Foundation began to offer local COVID-19 testing for public-facing village workers.

—Megan Bachman

Glen Helen closed to the public on March 26 in response to the pandemic. When the preserve reopened in September, it was under the new ownership of the Glen Helen Association. (Photo by Audrey Hackett)

Glen sold to local nonprofit

Glen Helen changed hands this year, ending months of uncertainty about the future of the beloved 1,000-acre nature preserve adjacent to Yellow Springs. Facing financial pressures exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, Antioch College sold the Glen for $2.5 million payable over 10 years to the Glen Helen Association, or GHA, a nonprofit group formed in 1960 to raise funds and advocate for the preserve. The deal was announced on June 10, and finalized on Sept. 4.

A significant part of the college’s history and identity, Glen Helen had been owned and operated by Antioch since 1929, when alumnus Hugh Taylor Birch donated the land to the college as a nature preserve in memory of his daughter. The Glen was among the assets repurchased by the Antioch Continuation Corporation after the college’s closure in 2007. And in 2015, a nine-year collaborative effort among federal, state, regional and local entities resulted in Glen Helen being permanently preserved. But the Glen proved difficult for the reopened college to operate and maintain. The situation became critical with the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced the closure of the Glen to the public and the cancellation of at least a year of public programs. Eight Glen Helen employees were laid off by the college in April, and a college trustee told the News thereafter that Antioch had no plans to reopen the preserve.

The GHA board worked with college officials through the spring to come to an agreement for the purchase of the Glen. As the News covered the ongoing negotiations, concern regarding the Glen’s fate mounted in the community. In mid-May, an anonymous local resident initiated a Save the Glen campaign to raise funds toward the GHA’s purchase of the preserve. That fund ultimately raised over $100,000 from more than 400 donors.

A purchase agreement was announced in June, and the college and GHA worked through the summer to finalize the transfer. Days after the initial agreement was reached, the GHA unveiled a $3.5 million fundraising campaign, the first phase of a multi-phase campaign to cover purchase costs and secure the Glen’s future. As of late December, current and past board members had contributed or pledged over $500,000 toward that campaign. Over the summer, the GHA also took steps to restore some of the furloughed Glen employees, including longtime Executive Director Nick Boutis. And the Glen’s new owners developed plans to reopen the preserve to the public and tackle deferred maintenance and other issues.

Local celebration ensued when, days after becoming Glen Helen’s new owners, the GHA reopened the preserve to the public on Sept. 9. Those re-entering the Glen for the first time in six months noted subtle changes in a forest largely unvisited by humans since March. As of year-end, the GHA has begun renovations to several buildings at the Outdoor Education Center, is planning to hire a land manager and is working toward restarting the Glen’s school and summer programs. Meanwhile, a “use agreement” ensures ongoing collaboration between the Glen and its former owner, Antioch College.

—Audrey Hackett

In the extended March 2020 primary, county voters rejected a sales tax increase that would have funded the construction of a new and larger jail. Villagers organized to defeat the measure; here, Pat Dewees spoke out against the proposal in March as part of a citizens group that continues to seek criminal justice reforms in

the county. (Photo by Megan Bachman)

Jail tax defeated by voters

In the delayed March 2020 primary, Greene County voters firmly rejected a proposal to raise the county sales tax to build a new and larger jail, with 62% voting against the measure and 38% approving it. Yellow Springs voters turned down the measure by an even larger margin, 84% to 16%. According to county officials, the new jail was needed to replace aging infrastructure and alleviate overcrowding at the downtown Xenia facility. The new 400-bed jail would have expanded existing capacity by 25% at a total construction cost of $70 million. The ballot measure sought to raise the county sales tax by 0.25% over 10 to 12 years to pay for the project.

The result was a victory for a group of Yellow Springs residents who campaigned vigorously against the proposal in the months leading up to the primary. Local activists feared that the larger jail would increase incarceration in the county, as well as divert funds from needed mental health and substance abuse treatment programs. The group crisscrossed the county to speak out against the project, shifting their campaign online after the pandemic hit in mid-March and the primary was extended to the end of April.

The News reported extensively on the jail proposal, with a dozen articles spanning as many months beginning in the spring of 2019. And the paper came out against the new jail, arguing in an editorial that the increased capacity was unneeded and the process leading to the proposed jail was flawed.

Following the measure’s defeat, the local group continued its work on incarceration issues, calling for reductions in the county jail population during the pandemic and beyond. Adopting the new name of Greene County Coalition for Compassionate Justice, group members are currently working toward cash bail reform in the county.

—Audrey Hackett

Around 400 villagers protested the recent killings of Black people by police on Saturday, May 30. (Photo by Chandra Jones-Graham)

23 weeks of antiracist action

For 23 straight Saturdays this summer and fall, a committed group of local activists protested, rallied or marched downtown in support of Black lives and to inspire anti-racist action in the village.

It all started with a protest on Saturday, May 30, in response to the killing of George Floyd, a Black man, by a white police officer in Minneapolis earlier that week. Sparking a wave of protests across the country, in Yellow Springs, an estimated 300 people lined Xenia Avenue and participated in eight minutes and 46 seconds of silence, the amount of time that the officer kneeled on Floyd’s neck. The following Saturday, more than 500 people marched through downtown chanting for change.

Villagers Jen Boyer and Bomani Moyenda organized the first three Saturday actions before a group of mostly young Black women took the reins, with their continued assistance. The group became “YS Speaking Up for Justice” and held weekly rallies and marches through the end of October. Leaders included Nya Brevik, Julian Roberts, Angela Allen, Julia Hoff and Alaina Hoff. Brevik told the News the weekly presence was important to keep momentum.

“It’s important that we continue to spread the message and to show we will not go away until there is real, genuine change,” she said.

At the weekly rallies, speakers presented information on themes ranging from voting rights to educational disparities to mental health issues. Villagers also shared their personal experience with racism during open mics. Moyenda was frequently the emcee, while Gyamfi Gyamerah led drumming. March routes through the village varied by week.

But as the summer wore on, tensions arose between protesters and Village of Yellow Springs officials, who were concerned that protesters were gathering without a permit or approved march routes. Protesters, meanwhile, believed the Village wasn’t taking action quickly enough in response to its demands for anti-racist action. They were also critical of how the YSPD handled a call from a purported KKK member who threatened to protest a Black Lives Matter-themed Fourth of July parade, which was canceled, in part, due to the threat. After several restorative justice circles and apologies from Council members, tensions eased.

When some of the initial organizers started college, a new group of youth organizers took their place and rallies and marches continued until the weather turned cold. The group is planning to continue the gatherings in 2021.

—Megan Bachman

Molly and Robert “Linsdey” Duncan, who were involved in a fatal shooting outside their home on Grinnell Road on Feb. 12, held a press conference two days later at the Yellow Springs Library. They were accompanied by Springfield-based attorney Gregory Lind, right. (Photo by Megan Bachman)

Grinnell Road shooting

Described at the time as a “shootout” by the county sheriff, a double fatal shooting in mid-February outside the Grinnell Road home of Robert “Lindsey” Duncan and his wife, Molly, shocked local residents, as well as family, friends and colleagues across the country of those involved.

Dead were Lindsey Duncan’s ex-wife, Cheryl Sanders, 59, and her husband, Robert “Reed” Sanders, 56, who investigators eventually concluded had driven to Ohio from their home in North Carolina with the intention of killing the Duncans.

Multiple 911 calls, including a distressed call from Molly Duncan, reported the shooting. Other calls came from neighbors who heard the shots or drivers on the road going by. First responders found Cheryl Sanders lying in the Duncans’ driveway, and Reed Sanders on the ground across the road, by the entrance to the former Camp Greene. Medics were unable to resuscitate the pair, and the coroner was called.

While the exact details of what transpired outside the Duncans’ home changed slightly with the documentation of different retellings, the following scenario emerged based on the Duncans’ statements, evidence from the scene and investigators’ findings.

The Duncans pulled into their gated driveway at 3443 Grinnell Road, just south of the village, shortly after 11 a.m., having gone for breakfast and coffee in downtown Yellow Springs. Molly Duncan was driving and Lindsey was in the passenger seat. Lindsey said he got out of the vehicle to check for mail in their mailbox, and it is unclear whether he was back inside the vehicle, getting back in, or still outside, when a man wearing a camouflage mask approached Molly’s side of the car with a gun.

According to the transcript of his Feb. 12 interview with sheriff’s deputies, Lindsey said he owns a gun, but had left it in the house earlier, and so he asked Molly if her gun was in the car. Both Duncans have Ohio concealed carry permits, which they told investigators they had obtained out of fear that Cheryl Sanders wanted to do them harm. They obtained the permits when they moved about four years ago to the area, where Molly has family nearby.

With Molly’s gun in hand, Lindsey said he exchanged fire with the man later identified as Reed Sanders. Lindsey said his ex-wife then pulled up in a vehicle, got out and also threatened them with a gun.

The Greene County coroner ruled the Sanderses’ cause of death as multiple gunshot wounds. Investigators reported finding three weapons at the scene and multiple shell casings. The Duncans were not physically hurt in the altercation.

A nearly four-month investigation — slowed considerably by the COVID-19 pandemic — ended with the presentation of the case to a grand jury on June 17.

Just a day after the shooting, however, Greene County Sheriff Gene Fischer had already told reporters that advance planning was suggested by the fact that the Sanderses were driving a car with counterfeit temporary Ohio plates, and Reed Sanders was carrying multiple forms of identification. Sheriff’s deputies also found two small cameras mounted on a post across from the Grinnell Road house with a livestream of the property going to a cell phone found in the Sanderses’ car.

Investigators later released a “checklist” found in the Sanderses’ car that spelled out their intention to cause harm to the Duncans.

In the course of the inquiry, investigators also traveled to North Carolina, where the Sanderses most recently lived, and to Texas, where both couples had long-term ties.

Lindsey Duncan is originally from Austin, and it was there that he began a career marketing health and nutritional supplements. The former head of Genesis Pure and then Genesis Today, he promoted his company’s products on such national television programs as “Dr. Oz” and “The View.” He left the company after settling a 2015 suit with the Federal Trade Commission in which he agreed to pay $9 million after being accused of “deceptively” touting “the supposed weight-loss benefits of green coffee bean extract.”

His ex-wife was at one time affiliated with the company as well, and she later continued in partnership with Reed Sanders in promoting various health and fitness products. She also was a former movie stunt woman with credits in more than 70 films.

Documented acrimony and lawsuits between Cheryl Sanders and Lindsey Duncan, and investigators’ confirmation of Duncan’s claim that his ex-wife made inquiries about hiring a hitman to kill him about five years ago, led Prosecutor Stephen K. Haller to conclude that Cheryl and Reed Sanders were motivated by “greed and hatred” in seeking to kill the Duncans.

Although investigators found evidence to support justifiable homicide, Haller said he chose to take the case to the grand jury in large part because of the gravity of the situation. He also was aware of some sentiments in the public suggesting that the Duncans’ stories didn’t add up, that the shooting was a set-up of some kind.

Letting the grand jury make the decision about culpability helped “put this to rest once and for all,” he said in June.

—Carol Simmons

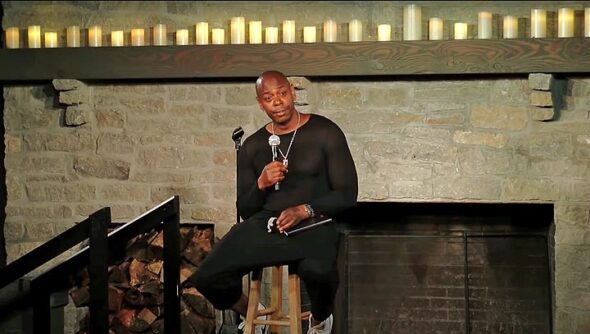

Award-winning comedian Dave Chappelle, who lives with his family just outside Yellow Springs, hosted weekend comedy shows at a property off Meredith Road in Miami Township throughout the summer. The events, which generally sold out and often featured other nationally known performers, were not, however, within the parameters of the zoning code, forcing the property owner to seek a temporary usage variance from the Board of Zoning Appeals. (‘8:46’ Screenshot, Youtube)

Dave Chappelle shows

Comedian and Yellow Springs resident Dave Chappelle was the focus of local attention for his activities in and around the village this year, as much as for his award-winning and sometimes controversial comedy.

The winner of the 2019 Mark Twain Prize for American Humor, considered the highest award in comedy, Chappelle spent much of 2020 sheltering in place and putting on outdoor shows at a rural property owned by Steve and Stacey Wirrig just north of town.

Billed as “An Intimate Socially Distanced Affair,” and familiarly referred to as Chappelle’s “Summer Camp,” the performances welcomed nationally known comedians and musicians to appear with Chappelle at a pavilion built by the Wirrigs in 2017. Among the entertainers was comedian and talk show host David Letterman, who came to town to film an episode with Chappelle for his Netflix show, “My Next Guest Needs No Introduction,” which is now available for viewing online.

The ticketed events began in June and continued two to four nights a week through the summer. A film of the first shows, presented by Netflix on Youtube and titled “8:46” (the amount of time a Minneapolis police officer held his knee on George Floyd’s neck causing his death), was widely shared on social media.

In July, however, the activities — which included a large, free July 4 fireworks display — came to the attention of the Township’s Zoning Inspector, who said the property owners needed to obtain a temporary zoning variance from the Miami Township Board of Zoning Appeals in order to continue presenting a commercial venture on agriculturally zoned property.

Steve Wirrig turned in a temporary variance application July 15, listing Oct. 4 as an end date for shows, which were not to exceed four a week. The appeals board hearing was held Aug. 6.

Nearly 190 people logged or called into the hearing conducted through the GoToMeeting online platform, and about 40 gave testimony, mostly supportive of the venture, for close to two hours before the appeals board members went into executive session to deliberate. Coming back into public session, the board approved the request with the stipulation that the show organizers work with neighbors to alleviate their concerns, particularly in terms of late-night noise.

The performances were halted a week earlier than anticipated, however, with a statement from organizers saying that the final six shows were canceled “out of an abundance of caution” after someone in their “inner circle” had been exposed to COVID-19.

Within that same timeframe, Wirrig submitted a request to modify the original temporary variance request in order to extend the shows into August 2021. That hearing was held in early November, and the zoning board approved the continuation after taking a mix of positive and negative testimony, again mostly concerning the late-night noise.

According to communication between Miami Township Zoning Inspector Richard Zopf and the county health department, Chappelle was given permission by the governor’s office before the start of the series to host an unspecified number of shows following certain COVID-19 safety precautions.

Attendance was limited to 400 ticket holders, with patrons required to wear masks and have their temperatures taken before entering the performance grounds, where seats were arranged at a distance of six feet between pairs. Performers also underwent COVID tests when they arrived in town, according to media interviews with the entertainers.

This month, news broke that Chappelle was in the process of buying the former firehouse on Corry Street in order to turn it into a restaurant and comedy club based on a model of the summer shows. The purchase joins a list of recent property buys in town, including the old Union School House, the building that houses the Smoking Octopus shop and two adjacent buildings on Xenia Avenue that support three storefronts, among others.

Chappelle’s year also included two Emmy wins and a hosting slot for “Saturday Night Live” the week of the presidential election.

—Carol Simmons

Villagers danced in the streets on Saturday, Nov. 7, soon after it was announced that Joe Biden had won the presidency. People waved American flags and Biden/Harris signs while dancing to such tunes as “Hit the Road Jack,” and “I Feel Good.” The impromptu celebration started after Gyamfi Gymerah and Bomani Moyenda brought their drums to the weekly peace vigil, which takes place at noon at the corner of Limestone Street and Xenia Avenue. Michael Casselli followed with a loudspeaker, and the music and joyful whooping attracted people from around town. The election was called for Biden at 11:24 a.m. that day after four days of tallying votes. (Submitted photo by Matthew Collins)

Elections, by mail

Two elections were held in 2020 amidst the pandemic, with most villagers participating in the franchise by mail.

A few hours before polls were set to open for the March 17 primary, the state of Ohio called off in-person voting, electing to extend the primary through April 28, with mail-in voting as the only way to cast a ballot.

In the end, 84% of local votes were cast absentee. About 15% of ballots were cast during early voting, while 1% of votes were cast via provisional ballot. Not surprisingly, turnout was down, with only 49% of registered voters casting ballots.

In Yellow Springs, three Village Charter amendments were on the ballot. Voters have opted to extend the mayor’s term from two to four years and expand voting rights in local elections to Yellow Springs residents who are not U.S. citizens, while voting down a similar proposal to allow 16- and 17-year-old voters to participate in local elections.

On the issue of extending the mayor’s term, 84% voted for the measure and 16% voted against. On the issue of enfranchising noncitizen residents, 58% voted yes and 42% voted no. And the issue of giving the vote to younger people was rejected 56% to 44%.

Miami Township voters overwhelmingly passed Issue 6, a renewal levy for Miami Township Fire-Rescue in the amount of 3.8 mills over five years, 83% to 17%. And county voters overall firmly voted down Issue 12, a 0.25% sales tax increase to fund construction of a new and larger county jail, 62% to 38%.

With more time to request an absentee ballot by mail, turnout in the village was up again for the general election in the fall.

Most Village voters opted to vote absentee in the fall, 54%, higher than the countywide rate of closer to one-third. Another 19% of village voters voted early in person, which meant that only a trickle of voters cast their ballots at Antioch University Midwest throughout election day. Overall, local turnout was 80%, higher than the county average of 75%.

The only local issue on the ballot was Issue 5, an 8.4-mill municipal property tax levy, which voters renewed for five more years by a nearly 3–1 margin.

Local candidates Dr. Steve Bujenovic, who ran for coroner, and Mark Babb, who ran for probate judge, both lost their races for countywide office. However, both did well in their hometown. In most other county and state races, villagers went overwhelmingly (90% or greater) for Democratic candidates who failed to carry the day.

One exception: the race for president. Yellow Springers overwhelmingly selected Democratic challenger Joe Biden over Republican President Donald Trump, 2,407 to 190 votes, taking 92% of the vote. Although Biden lost Ohio by six percentage points, he won the electoral college and the presidency.

—Megan Bachman

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.