The Party Pantry, located where Trail Town Brewery now stands, was a longtime Black-owned business in Yellow Springs. The business sold food and spirits for its adult customers, as well as treats for younger patrons who would stop by on their way home from school. (Photo courtesy of Antiochiana, Antioch College)

Black-owned businesses in Yellow Springs: an oral history

- Published: March 11, 2022

The following article appeared in the 2020–21 Guide to Yellow Springs: Downtown, Then and Now. Click here to read more articles from that year’s guide.

In decades past, a villager could walk through town and encounter a host of businesses owned by Black residents of Yellow Springs.

“Over the years, I think there have been upwards of 40 businesses,” said villager Karen McKee.

This summer, the News spoke with McKee, Jalyn Roe and Jocelyn Robinson, longtime Black residents, who shared their memories of the Black-owned businesses their families frequented growing up in Yellow Springs. Memories are often all that’s left of once-thriving businesses owned by Black residents; in 2020, only one Black-owned business operates downtown — The Yellow Springs Toy Company, which Jamie Sharp opened in 2018.

This story relies mainly on memory — of those interviewed and those cited in YS News articles from the past — to construct a timeline of many of the village’s beloved Black-owned businesses.

Memories of Black-owned businesses

McKee said that in her youth, many of the village’s Black-owned businesses were located along Dayton Street — it was the “primary business district” for Black shop owners, she said. A few also operated outside of the downtown business district.

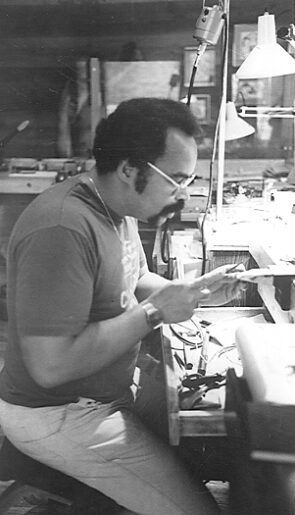

Mark Crockett at work in Rita Caz Jewelry in 1986, shortly after the store’s opening. (Photo from the YS News Archives)

Along Dayton Street, there was a shoe repair shop operated by James Johnson, which opened in the 1940s; the business was purchased by William Hawkins in the ’50s and renamed Hawk’s Shoe Repair. The shoe shop held special significance for McKee — her father, renowned former police chief James McKee, worked part-time at Hawk’s while still a student in Springfield.

“My mom used to walk home from school at Bryan High School and pass Hawk’s,” McKee said. “One day my dad was outside the shop while he was working and she walked by — and that’s how they met.”

Also on Dayton Street was Stag’s Cleaners, operated by Jason Stagner. It was one of two cleaners operating in the village at the time; nearby, on Corry Street, there was Joe Holly’s Cleaners, a white-owned business. Jocelyn Robinson said her family tended to patronize Stag’s over Holly’s.

“That’s where we felt comfortable,” she said. “Joe Holly was a cranky old guy — I don’t know if there was some bias there or if he really was just cranky, but I didn’t feel comfortable there.”

Bias wasn’t uncommon in Yellow Springs — famously, Gegner’s Barber Shop refused to accept Black men as customers, ending in a much-publicized demonstration on Xenia Avenue and the closure of the business in 1964. On Dayton Street, however, Black villagers were welcomed into the chairs of Black-owned barber shops and beauty shops.

Pemberton’s Barber Shop opened on Dayton Street in the 1940s, and was later replaced by the Village Barber Shop, owned by Emmett Burks, in the 1960s; behind the barber was the Village Beauty Shop — colloquially known as “Laura Lee’s” — operated by Laura Woods. (Darwin Lang later opened Lang’s Village Hair Salon in the same space in the 1990s.) The barber shop and beauty shop, according to Jalyn Roe, primarily served Black clientele.

“Burks’ was where all the Black kids and men had their hair cut,” Roe said. “Everybody was wearing big afros at that time and the kids used to call him ‘Butcher Burks’ because he would cut that stuff off and give a haircut that a middle-aged man would wear.”

In the 1960s, Roe’s parents, Jake and Maxine Jones, opened the MaJaGa Bar and Night Club on Dayton Street; it was located where the Gulch now operates.

“My dad said he named it after his three queens: Maxine, Jalyn and Gala,” Roe said, naming her mother, sister and herself.

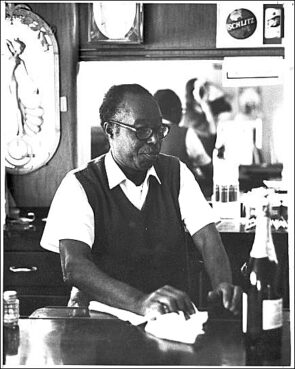

Hillard “Com” Williams at his W. Davis Street restaurant, Com’s, in the early ’70s. Williams ran the popular restaurant with his wife, Goldie, for nearly 30 years. (Photo courtesy of Antiochiana, Antioch College)

Another bar previously operated in that space, and when the Jones’ took it over, they installed a stage and loft seating area and hosted performances from area bands. As the News reported, the locally formed psychedelic rock band Mad River got its start at the MaJaGa, playing its first performance there in 1966.

“It was a themed gathering place, Bohemian-type decor with big straw and leaves — it was just beautiful,” Roe said. “But, of course, Yellow Springs didn’t want anything to do with something like that!”

Roe said MaJaGa was picketed by disapproving villagers when it opened — which only strengthened her parents’ resolve to keep the business open.

“My mom used to laugh, she said, because 95% of those picketers became patrons,” Roe said.

Jake and Maxine Jones operated several businesses in the village in the ’60s and ’70s. Roe said they knew they wanted to be village entrepreneurs from the time they married in the 1940s — they were wed in custom-made business suits. Their first venture was the Party Pantry, which opened in the ’60s at the corner of Dayton and Corry streets. The business sold food and spirits for its adult customers, as well as treats for younger patrons who would stop by on their way home from school.

The Party Pantry was also one of the sites of Gabby’s BBQ; Gabby Mason, well-loved in the village, operated his business out of several locations over the years, including his Stafford Street home. In the ’60s, he cooked and served his signature barbecue from a portion of the Party Pantry that Jake Jones, who was a good friend, rehabbed specifically for that purpose.

The Joneses sold the Party Pantry to Shelley Blackman Sr., who, looking to expand, moved to a newly constructed beer, wine and liquor drive-through at the rear of Kings Yard in the early 1970s.

The large, glass-fronted building would go on to be the home of Rita Caz Jewelry Studio, and now houses the House of AUM and Little Fairy Gardens.

The Joneses were also the first Black owners of a Cassano’s Pizza franchise, their third village business, which opened at the corner of Xenia Avenue and Corry Street, where the Winds Wine Cellar is now. Roe said she remembers a bit of controversy surrounding that business, too. This time, folks were concerned about the sign — which bore the full name of the business, “Vic Cassano Mom Donisi Pizza King” — being too garish.

“As a franchise, they had to do everything the franchise way — but Mr. Cassano allowed them to change the sign to reflect the village’s culture.”

When the Joneses closed the Pizza King, another Black-owned business moved from across the street to fill the vacant space — Gabby’s Pit BBQ, which Roe said her mother helped run for a time.

“My mom and Gabby’s wife, Mary, did all the marketing and business-running, and Gabby made the food and the sauce,” she said.

Another drive-through alcohol establishment was Eddie’s Drive-Thru, owned by Eddie Ellington, on Xenia Avenue. McKee said her parents would go through Eddie’s to pick up cream sodas for floats once in a while for a treat that was “pure sugar — it sent you into orbit,” she said. Eddie’s also served pizza, which is fondly remembered. The space later became Peach’s Grill, named after its talented original Black chef, David “Peach Fuzz” Sebree.

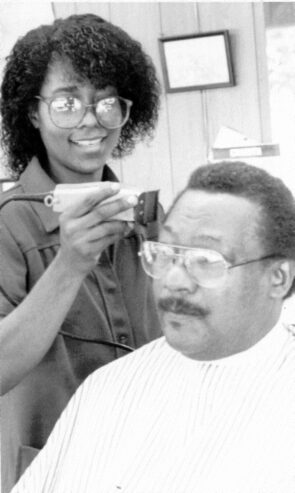

Village Barber Shop owner Emmett Burks and his daughter, Charita. (Photo from YS News archives)

Further down Xenia and onto Glen Street was an electronics shop owned by Bill and Camilla Harris. The Harrises went on to open the bowling alley; that building, located between Village Automotive and Dollar General, is now owned by YS Brewery for storage and events.

The village’s Black-owned businesses weren’t all concentrated downtown — in the 1940s, Oliver Henry opened a small grocery store at the corner of High and West Davis streets where Michael James Salon now stands; in the 1950s, Henry Williams operated a grocery and pool hall in the same space.

Right across High Street on Davis was Com’s, a popular restaurant for both town and gown, opened by Hillard “Com” and Goldie Williams in 1945. Villagers still remember Goldie’s gumbo soup and fried chicken. The same site was later DGs, where “Peach Fuzz” honed his cooking skills and was remembered for his swiss bacon burgers. Its final incarnations were as Trisha Di’s and Sharon’s, and the art deco bar back from the location now resides at Peach’s Grill. The site of the businesses is now a private residence.

There were also many home-operated businesses over the years, offering construction, locksmith services, plumbing, realty and catering. One such home-operated business remains: Hershell Winburn has owned and operated Winburn Janitorial Service for 39 years.

By the 1980s, many of the Black-owned businesses in the village closed; in 2010, the News reported that, after Mark Crockett opened Rita Caz Jewelry Studio in 1986, Emmett Burks, who was retiring from his business, remarked that he and Crockett were the only Black-owned businesses in town at the time (though Hershell Winburn’s aforementioned business had actually opened several years earlier).

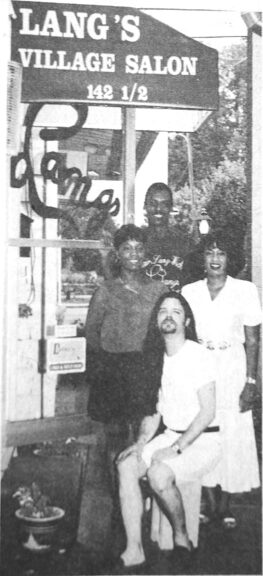

Several Black-owned businesses opened and closed in the 1990s and 2000s, including Meskie Brown’s Ethiopian Restaurant, Lang’s Village Hair Salon, Locksley and Guy Orr’s Gypsy Café, children’s clothing store Munchkidoodles, Pyramid Books, Keahey’s Graphics, Keith and Kecia Tolliver’s Kecia’s Treasures (featuring West and Central African folk art and world clothing) and Rolling Pen Book Cafe. Rita Caz closed in 2017 after 31 years.

“The question everyone has is, what happened?” McKee said. “There used to be a significant number of Black-owned businesses — there’s not a simple answer to the question.”

Reasons for decline

Black Americans have always faced barriers when it comes to opening and maintaining businesses. The blight of slavery, from the outset, barred enslaved Black Americans from property ownership for decades. When Black Americans were able to build communities in the years that followed, violence from whites could and did often destroy that growth. June of this year marked the 99th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre, when whites burned to the ground the thriving Black community of Greenwood, Oklahoma — known colloquially as “Black Wall Street” — and killed more than 100 Black residents in one of the worst incidences of racially motivated violence in American history.

Staff of Lang’s Village Salon, 1994, clockwise from top: D.W. Lang, Cheryl Williamston, Rick Stanley and Rosenda Chatman. (Photo from YS News archives)

Historically, Black Americans have also been denied loans for businesses from financial institutions — a practice that continues well into the 21st century. In a report that studied American small business loans between 2012 and 2017, the Federal Reserve concluded that small businesses owned by Black entrepreneurs were the least funded among those who had applied for loans during that time period. Black businesses have also been the hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, with the National Bureau of Economic Research reporting in April that 41% of Black-owned businesses in the U.S. had been shuttered, compared to 17% of white-owned businesses.

Though Yellow Springs perhaps had a higher than average incidence of Black-owned businesses for a community whose population was mostly white in the 1960s and ’70s, there has been a steady decline in Black-owned businesses since the 1980s. Jocelyn Robinson said the declining diversity in the village’s businesses has been multi-faceted. The loss of industry in town, she said, contributed to the decline of not only Black businesses, but Black residents in general.

“The demise of Vernay, the college, the light technical and industrial base that the village had — all of those places had made commitments to employ a wide range of people,” she said.

Moreover, shifts in the country after desegregation played a part in the decline of Black-owned businesses — not just in Yellow Springs, but everywhere.

“There were Black entrepreneurs, and as desegregation continued, it diluted the stream of Black business people who had to be self-reliant and resilient,” she said. “And it took decades in some cases, but going into the ’80s, that change was solid.”

She also said that, historically, the realm of business wasn’t the only area affected by a decline in Black representation in the village.

“I think it’s misleading when you talk about Black businesses and downtown, because there were Black people of authority and responsibility in every aspect of life,” she said.

During her childhood in the 1960s, there were numerous examples of Black villagers in leadership positions, including Police Chief James McKee, Mayor James Lawson, Fire Chief Andy Benning and longtime school board member Paul Ford. Many of the teachers at the village’s public schools, she said, were Black.

She echoed a sentiment made by the late Phyllis Jackson in a 2010 YS News story, after reflecting on the same period of Black leadership in the village.

“You’d think this was a Black town,” Jackson said.

Records of many of the village’s Black-owned businesses are preserved in “Blacks in Yellow Springs: A Community Encyclopedia,” which The 365 Project published in 2016. McKee was part of the committee that assembled the reference book, and said that community recollection was the primary source for its entries.

Jamie Sharp is the owner of YS Toy Company.

“We literally were operating off the memory of our elders — Phyllis Jackson, Paul Graham, Betty Ford, Isabel Newman — a long list of people who remembered the village in those days,” she said.

As many of the village’s Black elders have passed on — Jackson and Newman died this year — Jalyn Roe said that the torch of memory is being passed to a younger generation of Black villagers, like herself, McKee and Robinson.

“I remember, there was a Black dentist in town named Dr. Pemberton, and he told my mom, ‘We’re the bumpers — we have to carry on to make sure the Black businesses and people stay, that they have us to bump up against,” Roe said. “Now we are those bumpers — we have to tell the stories.”

Robinson said that the village’s shift to a tourism-based economy over the years also contributed to the loss of Black businesses — the kinds of businesses that kept the village self-sufficient, and which were undercut by the growing world and the availability of those services outside of town.

The ongoing pandemic, however, has impressed upon her the ways in which a self-sustaining village, where villagers don’t have to travel and interact with the world at large for necessities, could be an answer to the problems the pandemic has created.

“The only way we’re going to survive — politically, economically and in terms of public health — is to have small, self-reliant communities,” she said.

McKee said that’s the kind of business district she remembers from her youth — and hopes the village can regain, with opportunities for Black business owners in the future.

“It was a thriving business district, and you didn’t have to go out of town to get the things you really needed,” McKee said. “We were a small town that supported one another.”

14 Responses to “Black-owned businesses in Yellow Springs: an oral history”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

Wow William Hawkins was my grandfather,awesome article.

Excellent article! YS has such a rich legacy that is in danger of being lost. Another aspect to include would have been Mr. Wheeling Gaunt donating the Dayton St. business district to Wilberforce University who was the property owners for a number of years. A definitive heavy influence on that corridor. Presently Mr. Chappelle has been buying many businesses essentially building back black business ownership.

Mr. Johnson! I would love to find your book and further information about Mr. Gegner!

I believe the first Hawks shoe repair shop was on Xenia Ave. in a little log cabin which was probably removed to make the King’s Yard.

Tim Benning’s parents Reginald and Kumi Benning owned a deli at the corner of Dayton and Cory in the late 70’s

So very sorry to hear of the passing of Mark Crockett, such a kind man, gifted jewelry maker, musician, Township Trustee,etc…such a loss to the village.

Without any doubts, it is so cool that you covered this topic and enlightened people about Black-Owned Businesses In Yellow Springs because, from my point of view, it is really important to know the part of Black people’s history. All these memories are so valuable and it is so cool that they have remained in the memory of so many people. Also, I am amazed by the concepts of these enterprises and it is so cool that there were places where Black people could feel comfortable without facing any bias. Also, it deserves a huge respect that The Joneses were also the first Black owners of a Cassano’s Pizza franchise because it is a great achievement and, of course, it contributed to development of this pizzeria to a great extent. I really like when the whole family is engaged in running business and it is so wonderful that we can observe it in Gabby’s Pit BBQ because it indicates the cohesion and contributes to its development. I was so inspired to read this article.

You missed a small boutique on xenia Ave. Owned by Dorothy Allen and Jackie Blackman, that sold ready made clothing, one of a kind designer wear and performed alterations.

I have fond memories of going to the Beauty parlor with my grandma Applin. While grandma got her hair done, sometimes I got mine brushed but more often I played outside on the little sidewalk with a kid that lived behind the shop.

Very informative article especially one of my family members spotlighted in the article Msrk Crockett who made jewelry.

Thank you for this important piece of history. So many businesses I frequented as a local and then as an Antioch student. A picture of my brother Mark Crockett at his work bench nearly 36 years ago.

Thank you.

An article about Black businesses in Yellow Springs should refer to the several race riots in neighboring Springfield Ohio (1904,1906,1921) instead of the distant Oklahoma Black Wall Street uprising.

The Springfield violence was reported in the New York Times.

See Ohio Valley History, Volume 6, Number 1, Spring 2006, pp 27-44

published by the Filson Historical Society and Cincinnati Museum Center.

I enjoyed the article immensely from my residence in YS from 1957-1971. I frequented Burks Barbershop for years even after moving to Dayton. I frequented Mr. Williams restaurant, even before moving to YS in 1957. What was not mentioned in the article was that Mr. Williams was also employed at the Kettering Laboratories as Head Custodian where I knew him for a number of years. He is mentioned in my book on C.F.Kettering as Boss Kett pausing while entering in the morning to inquire how he and his wife were doing. Another item in the article, Gegner’s Barbershop, I was one of five individuals at the time refused service, and was a member of a resident’s group, named ACTION, which stood for (Ad-Hoc Committee to Integrate Optimally Now)

Kevin E. Taylor, Miss Laura did my mother’s hair for years. I have wonderful memories of reading my kids’ books there in a chair while my mom got her hair done. I’ve thought of Miss Laura many times over the years since my mother passed away.

Laura Lee Woods, is my Grandmother and I live there with her!! I remember the Village Beauty Shop, going across the street getting ice cream. My Hometown Yellow Springs, Ohio